Nick and Tom pulling on Excalibur at Disneyland during their last vacation in California before moving here.

For me, one of the absolute high spots of our collective lives together was the day that Nick and Tom came back to live with us in Santa Cruz during the summer of 1999. Nick turned 13 that summer, and Tom turned 10 in the fall. They had only been in France for two years since the rest of us had left, and during the last 18 months of that period had seen us regularly for vacations. But those brief vacations couldn’t satisfy the hole inside me, and I ached and ached almost the whole time that they were in France. Something was missing, and nothing could take its place.

I was simply thrilled to bits that they were coming home. That’s how I felt, so happy, that and a palpable sense of relief.

Now it would all be okay again. The legal battles that our move to the US had set off were almost over. The furniture was still in France, but the sheer length of time that we had been deprived of it argued against the French courts keeping it there much longer. The boys were back, and the Santa Cruz County Child Support prosecutors had finally been driven away. We’d all been together before, and had made it work and now we could do it again.

The calm before the storm! Marie-Hélène with her four, all looking angelic, on a day trip to Pleasanton in June 1999.

“That’s how it should have worked out,” I think to this day.

Nick and Tom’s two years away shouldn’t have been that significant an absence, should not have been so significant to the life of our big blended family, but somehow it was. Combined with whatever else had been going on within us and without us, their absence somehow turned our little community, the three families that we had welded into one during our first years together, into something else, something with a centrifugal force.

The Hanlons were always so welcoming to all of us. Alban, Tom and Daphné grab a bite at their place during Tom’s spring 1999 visit.

Of course, all families experience that centrifugal drift of the teenagers toward the outside world. It’s perfectly normal. In ours, the centrifugal drift of the teenagers coincided with a growing opposition in each case to the parent who was not his or hers. Doubts about the step-parent added to the teenager’s confused mixture of growing independence and continuing need. Our two original one-parent families would ultimately be reinstated. That was years away, but the couple of years after Nick and Tom’s return home in 1999 saw its genesis.

I began to realize that we all had a problem soon after Tom started at Happy Valley School, where Daphné and Alban had been happily ensconced for two years already. Tom, who is not a whiner, far from it, almost immediately started complaining that some of the boys in his class were picking on him. Alban was in the class too, and we parents didn’t understand what was going on at all.

Another one taken during the same visit to the Hanlons, again by Annie. April 26, 1999. From left to right, Alex, Charlie, Brendan and Nick.

Within a few weeks of the beginning of the school year, the school called the parents in. Although I have our diary record of Marie-Hélène’s and my meeting at the school, I do not have a record of why it took place.

The teachers in the meeting told us that several boys were picking on Tom, and gave us their names, and then gently pointed out that they were all Alban’s friends. Something went « clang » in my head : Alban didn’t want to share his new world with Tom! He had liked settling down at school in Santa Cruz and making his own way here. Tom risked changing all that.

We vacationed together in England during the summer of 1999 before they moved in with us in Santa Cruz. Tom is swinging out over the Thames from an island in Hurley, near Marlow.

Nothing went clang in Marie-Hélène’s head: she could not accept the possibility that Alban had played any role here. One of the teachers also mentioned that she had seen one of the boys they had named, one of Alban’s friends, together with Alban, helping Tom with his homework on one occasion.

The teacher probably brought up this anecdote to reassure the mother that her son was, like all children, capable of different feelings and attitudes. She was a thoughtful teacher doing her best to paint a complete portrait.

But the center of this portrait was the possibility that Alban was picking on Tom. If so, why? I don’t know. In later years, beginning in 2008, when Tom would return to Santa Cruz from his mother’s place in Paris, Alban and his friends welcomed him with open arms.

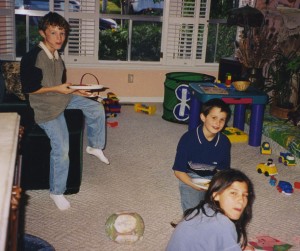

September 1999. The first birthday party after the boys moved back in. I think that this was a joint affair for Daphné and Nick, whose birthdays are four days apart in the middle of the summer.

In short, if it happened, it was a bit of an anomaly for our blended family and for Alban. But it happened, if it did in fact happen, to Tom. Nick was already in seventh grade, and in middle school. He had the usual issues as the new kid in town, but at the same time his classmates were all new to the school if not to each other. I thought that his transition would be harder than Tom’s, but because of Tom’s feeling of being unwelcome it was easier.

The feeling of being unwelcome that he experienced at Happy Valley School, and by intimation from his own brother (they never called themselves stepbrother or stepsister), upset him. Tom had been less clear than Nick in his desire to return to live with us, and feeling unwelcome must have turned him even more away from the rest of us. To me, he felt sullen and resentful at times, qualities which were new for him. He had always lived inside himself more than the other three older siblings, but it was a contemplative solitude, sometimes wild and crazy, but definitely not bitter.

One thing that I must insist on to close this anecdote is that Alban is normally the definition of kindness. Year after year, he constantly looked after Charlie and Alex, shepherding them through skateboarding and soccer, the trampoline and happy Valley School, always gently pointing them in the right direction. He skillfully navigated our complex intertwined families at every turn, careful never to offend one or the other.

Something must have prompted it if indeed he acted out of character when Nick and Tom returned to our collective home. To this day, I wonder about what happened and what could have caused it.

One of those of the eight of us taken in October 1999 by a professional on our way to or from the beach.

Marie-Hélène too had reserves about Nick and Tom’s return. It was a return to a status quo that she had previously adjusted to and lived with very well in France. She had even been instrumental in winning their return, by convincing the French court-appointed psychiatrist that they would be welcomed in Santa Cruz. So what happened after they returned to make them unwelcome?

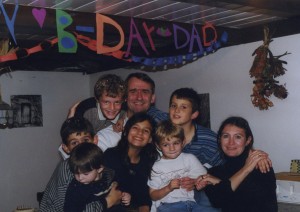

My birthday in 1999. Amélie, our au pair who lived in the cottage and helped Marie-Hélène look after the children that school year, took the photo.

That’s the $64,000 question, and I think that I have handles on it. The handles come from anecdotes dating back to the early days of our blended family. From time to time, I noticed that she was a little uneasy about taking on Nick and Tom. She already had two children of her own: two more were going to be a lot of work.

In January 1997, we drove to the court in Versailles to pick up the final judgment of divorce that determined their future. Marie-Hélène and I had been living together for over two years already. This judgment was the only way that we could see losing custody of Nick and Tom, and it was a very real possibility.

But no: the Versailles court held that Nick and Tom would continue to live with us! I couldn’t believe it, and rushed back to the car full of glee to announce the news to Marie-Hélène.

She put a brave face on, but underneath it I could see a definite unease. She was visibly worried. She soldiered on, of course, as she always did, but it was clear that she would not have had a lot of regrets if things had worked out differently. The care-taking responsibility assumed by the maman of our blended family had more than doubled overnight: more than doubled, because the blending itself added to her burden.

Part of the dynamic that influenced us all was visible in another anecdote, this one dating from around 1996, I forget exactly when, during our first years together. We all went to see The Lion King, the new Disney movie, at the local cinema in Rambouillet, the market town near our home in the forest southwest of Paris. All of us were then the six initial members of the family: Charlie was being babysat at home.

In the limo on the way to or from Florida in the summer of 2000. Nick has lilac hair highlights, and he and Alban a big smile. I don’t remember what Tom was upset about, but seeing his expression there now saddens me. It should have been a happy time.

As ever, we arrived close to the show time, and there were no blocks of six seats together remaining when we arrived. There were four seats together. Nick and Tom went to sit in another row a little behind the four seats together: Marie-Hélène expected me to sit with her, Daphné and Alban. I did so for a minute or two, but felt odd and tried to figure out why. Of course: it wouldn’t be fair to exclude Nick and Tom from the rest of us. I moved back a couple of rows to sit with them, and watched and loved that fabulous film, which I still think is the best animated film ever. Music, storyline, characters, it was all wonderful.

I barely gave changing my seat a thought. Marie-Hélène was watching the movie with her children, I was watching with mine, and all the children had been treated the same. Only after the film did I realize how slighted and hurt Marie-Hélène felt. She could barely talk to me, and when she did berated me forcefully for not sitting with her in the cinema. Obviously, that wasn’t the way that I saw it: I was making a simple calculation ensuring equal treatment for each pair of children and that my pair did not feel slighted. I tried to explain all that, but none of it mattered.

Tom’s birthday cake in 2000. Our furniture and dishes had only just been delivered. Note the French flag on his cheek!

The point of the anecdote is that Marie-Hélène felt hurt by my looking after Nick and Tom when taking care of them conflicted with taking care of her. More importantly, she felt hurt as much for her children as for herself. By sitting with Nick and Tom, she felt that I was putting them before Daphné and Alban. Not true, of course: I was keeping things balanced by not leaving any children without his or her parent.

That was my first inkling that I was expected to put Marie-Hélène before Nick and Tom, all other things being equal. It was my first inkling, or more likely the first that I remember, that I was in some sense supposed to favor Marie-Hélène’s children. This was my lesson from the Lion King cinema seat swap debacle. That night, walking around in Rambouillet after we left the cinema, with Marie-Hélène furious, I felt very worried realizing what the scene had been about.

During Nick and Tom’s two-year absence, even though I sought to avoid it, Daphné and Alban were effectively favored a lot, simply because they were with us when Nick and Tom were not. Nick and Tom were excluded by their absence from fun stuff that the rest of us automatically did together. I tried to arrange the major adventures to coincide with Nick and Tom’s visits. But nothing could change the fact that most of our weekends exploring our new world, most of those spontaneous day-to-day moments that make a family, were not shared with Nick and Tom. In that sense, Daphné and Alban were favored.

I paid for Nick and Tom in child support payments to their mother, but they saw very little of these, and may not have really registered that I was still paying for them. I paid for Daphné and Alban directly, for everything, every day. In that sense too Daphné and Alban were favored: they must have noticed it. Their mother sought to affirm their father’s love for them by bringing everything that she could about their father’s support to their attention. But that was a stretch, even for her, because he paid almost nothing (it was like getting blood out of a stone) and spent a lot of time convincing his children how poor he was so that they would not ask for more. In short, I assumed their father’s support responsibilities, face to face and day to day.

The return of Nick and Tom marked the end of that kind of favoritism for Daphné and Alban. All of the children now shared the pie as equally as I could manage it. I don’t think that’s how it felt to Daphné and Alban. It appeared as if they felt disfavored by the boys’ return. Their mother was convinced that I had favored Nick and Tom, even when the circumstances of their absence made such favoritism impossible. Now that they were all together again, Daphné and Alban’s conviction that they were the disfavored seemed to me to increase.

What did Nick and Tom bring into this already unhealthy mix? The poison that Sunshine had poured into them during their two years with her. She had always been extremely hostile to our new family, even when the boys lived with us in the Forest of Rambouillet and visited her each week. In a way, there’s no way around jealousy in a situation like that, when a parent sees her (or his) loved one replacing not only the parent herself with a new significant other, but also sees that same significant other looking after her (or his) children.

But Sunshine went overboard. I used to say, only half in jest, that while the sexist stereotype is that a woman lives for their marriage, she had lived for her divorce. While Nick and Tom were living with us in France, they could surmount this constant hostility to their new family. It would take them a few hours each week after they returned to our place, but then they were over it until the next time.

When they spent two years with her in Paris, Nick and Tom were rarely given the opportunity to escape from the obsessive pressure-cooker of their mother’s seething rage. Marie-Hélène was the embodiment of evil in her twisted jealous world. It didn’t matter how she kind she had been to the boys, or how calm she had been in the turmoil that surrounded us all. If anything, these attributes made Sunshine feel even smaller and more resentful. So she worked on her sons.

I suspect that Marie-Hélène wasn’t the only subject of her vitriol. Sunshine had somehow linked Daphné and Alban with Marie-Hélène, not as a mother and her children but as common foes, shared causes of her misery and jealousy. I can’t know or understand what Sunshine said about them, but Daphné and Alban were also her targets.

Within the pressure cooker that she had created, Sunshine took advantage of the boys’ worries about being left behind in France to suggest that I would favor Daphné and Alban in the US as a way of currying favor with Marie-Hélène. They were both watchful when we spoke on the phone, looking for examples of that favoritism. They were watching like hawks.

This was Daphné’s bedroom door in 2001. The “Jesus Loves You” sticker was on there for quite a while. Daphné is pretty much the opposite of religious. The point of the sticker can be understood by combining two facts. First, her bedroom door faced Marie-Hélène’s and my bedroom door. Second; the sticker continues “Everyone else thinks you’re an asshole.” Guess who that was directed towards! She was fourteen. The problem was that her mother was starting to agree with her!

That was the poison pill that their mother sent back with Nick and Tom to Santa Cruz, along with a readiness to find fault with Marie-Hélène, an excessive watchfulness and shared obsession about favoritism. It came from both directions somehow, Daphné and Alban on the one hand and Nick and Tom on the other, that excessive worry about being disfavored.

Where was I in the first years after the boys returned? At the office, that’s where. Someone had to pay for all this, and that was my part of the bargain. I was at Wilson Sonsini until September 2000, a year after Nick and Tom’s return, as Silicon Valley’s number one law firm stretched itself to the limit to handle the internet bubble. The hours were terrible, and my time at home with the family very limited. I had more time at home after moving in-house at Atmel, where I stayed until June 2003, but my childcare role remained limited. Nick, the oldest, was sixteen when I left Atmel.

Marie-Hélène would say to this day that I favored Nick and Tom. How I could do that when I was there so little, and when she did almost all the child care, is beyond me. I was very careful to spend money evenly on all the children. That was within my power. I didn’t even feel that kind of favoritism. I wanted them all to feel good, and all to feel loved. Somehow, I failed.

We had a halfpipe built for the skateboarders, whose leader was Alban. Here it is, half built. Unfortunately, that’s how it stayed. It took almost a year for the contractor to complete (he fitted it in around his real work, thus giving us a great deal), by which time no-one was still that interested. So many things to do!

The way that I see it is that our family history turned into a series of Lion King cinema seating debacles. I was being careful to treat all the children equally, but only favoring Daphné and Alban would have satisfied their mother, and ultimately them. Needless to say, I couldn’t do that.

Needless to say, this point of view is not shared!

Every family deals with sibling rivalry on some level. In the more simple nuclear family, when the parents don’t divorce or die during the children’s upbringing, such rivalries typically do not win the day. There is enough in common within the family, enough love from all angles, that the rivalry does not get the upper hand. Or if it does get the upper hand, there is something seriously wrong.

Charlie and Alex being cute in July 2001 in les Jardins des Tuileries, the Paris gardens on the banks of the Seine where their maman and I first courted almost ten years before with our four other children in tow. It was always a pleasure to visit the Tuileries again.

Maybe there is something inevitably out of whack in the nature of blended families. Each parent tends to wonder about the relationship between his or her children and the other parent. The mother worries that the step-dad will be mean to her children, and perhaps punish them or yell at them more than his own. The father worries that the step-mom will mother his children less than her own, and perhaps like them less. Some of those happened to some extent in our little troupe (guess which, from my perspective!), which helps explains how our particular sibling rivalries expanded until they were almost overpowering.

Our two-year separation of the two initial pairs of children made a difference in a way that all the difficulties that we had gone through after we moved in together in France did not. The dynamics in place during the children’s separation were hard to see at the time and even harder to adjust for. They never made sense to me as an explanation of how the family relationships deteriorated, but from then on in, I think that as a blended family we were in some sense doomed.

Plus, of course, and we’re back to the beginning of our reflections here, the children were becoming teenagers, and thus naturally knowing everything and dissatisfied with everything else! They were becoming independent and moving away from the parents in any event. The most visible quirk in our case is that they tended to move further away from the step-parent, and less far away from the biological parent.