Girls, those strange creatures who still lived somehow outside of daily life, had become brief but intense obsessions.

Walking down Marlow High Street, I would have conversations with myself about why this girl walking the other way wouldn’t acknowledge my smile, or why that girl in the tobacconist’s would look away as soon as she caught me looking at her. Then there was the pressing question of why a girl was much more likely to smile at me when she was on another boy’s arm than when she was alone. All very perplexing. And underlying these more simple questions was the big one: why was it all so difficult, even the simplest and least threatening things? Was it because of my long hair? Skinny body? Did something about me make girls uneasy? I was unable to figure out, or even get a handle on, why we could not simply smile and talk to each other.

For years, I bounced off walls, ricocheting backwards and forwards with girls like the silver ball in a pinball machine, jumping almost randomly here and there. If something clicked early in a conversation, or if some cute coincidence revealed itself, I would open up and jump. Other times, even after long and rewarding heart to heart discussions, I would close up and skulk away, silently.

In retrospect, some of the jumps seem more significant than others, for reasons that are not always clear, even to me. Stella was one. Meeting her was a real high. It was in Oxford, one of my favorite towns, scenic, cultured, and full of students, where Mark, a sort-of friend from Borlase’s, was beginning his university course. I was visiting him the same weekend that Stella was visiting someone in his circle in the same College. There was a muted party in their staircase (rooms go up staircases in Oxford colleges, not along corridors!), not a lot of people, but with a good soundtrack played on a fabulous stereo – Derek and the Dominos’ album “Layla and other Assorted Love Songs” repeat-played for quite a while – and Stella was lovely, warm and interesting. Sparks flew! Of course, the party came to an end without any follow up on my part, but I could tell that she liked me. And the feeling was mutual.

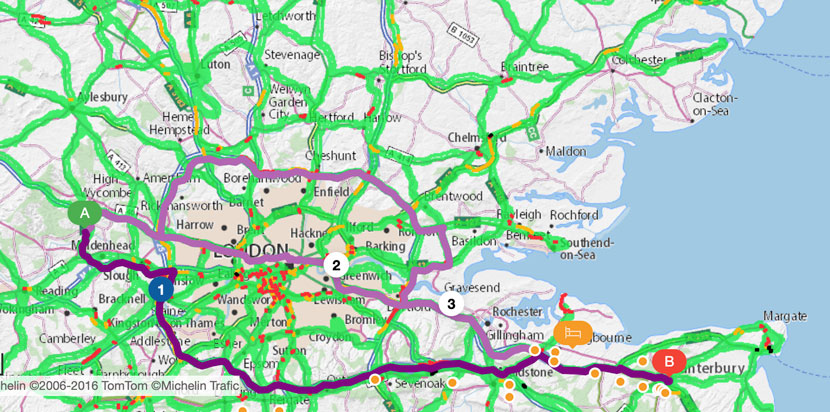

On a whim, I thumbed all the way around South London to visit her, just a week or two after that party in Oxford. The trip to the University of Kent in Canterbury, where she was studying, southeast of London, took five or six hours. It was a very difficult journey from Marlow, west of London, before the M25 motorway was built, ride after ride after interminable ride. Thumbing the more direct route across London was simply not feasible.

Not surprisingly, I arrived much later than expected. Miraculously, despite arriving without an invitation, Stella was pleased to see me, reassuring me that of course I was welcome, even though it was the end of the evening by the time I arrived. I hadn’t even warned her that I was on my way! We again got along fine, talking easily despite there being none of the booze or other partying that we had indulged in in Oxford, but before long it was time to sleep. I lay down dutifully on the floor of her dorm room in my sleeping bag, and she lay down in her bed.

We each tossed and turned, restless and keyed up, and exchanged a few words from time to time. I was very conscious of her physical proximity. But believe it or not, I was also questioning my motivation for being there, which did interfere with bouts of high strung desire. It had not occurred to me that by showing up late on a Saturday evening, I was broadcasting that desire loud and clear! But I was still unsure of my motivation. That was just daft! She was lovely, and we already enjoyed our time together more than we each could reasonably expect.

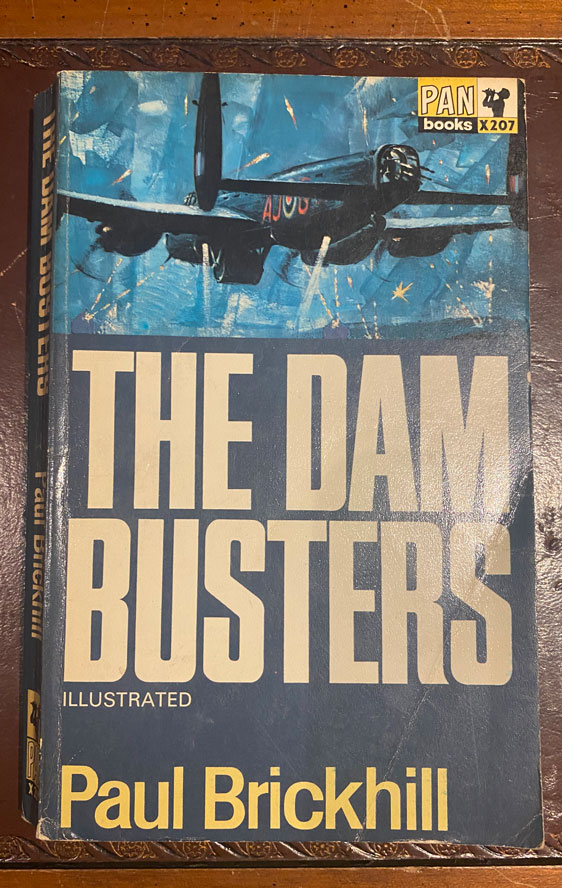

In my head I was worrying about the Dam Busters. The what?! They were an RAF squadron during the war which made a deserved name for itself beginning in 1943, when they bombed German dams in the Ruhr Valley. Paul Brickhill’s book on their extraordinary exploits clarified what “balls of steel” means, the kind of courage that there was rarely any cause for during my youth. Mark had told me that Stella’s father had piloted one of the eleven Lancasters that made it back to base after that mission (eight were not so lucky). I was really impressed, and laying on the floor next to her bed was wondering if perhaps that who her father was, what he had done, had influenced this impulsive visit.

Out of the blue, in the middle of these reflections, she invited me to join her in bed. Adolescent fantasy becomes amazing reality, and they lived happily ever after! Well, that’s what could have happened, and if I had been less obsessed would have happened. But, worried that I was there because of her dad more than because of her, I made some excuse, stayed on the floor where I was tossing and turning, and eventually fell asleep. How did I refuse such a brave and kind invitation? What an idiot!

I had the Dam Busters in my head, but elevating an unrelated fact into a position of decisive importance was simply absurd. I was a hippy, had no personal interest to further in the military (her dad was by now at the top of the RAF’s pyramid), and was laying on the floor next to her bed because I really liked her. The more I liked a girl, the more difficult time I had with her, but she had made it so easy. Not surprisingly, I never saw her again.

A few weeks later, Mark told me that he had apologized to Stella for whatever I did when I had visited her, and has almost never spoken to me since. He can’t have understood or even known what actually happened. She was very unlikely to have explained it to him. There’s no way that she herself could have understood the bizarre way that I had acted; she didn’t even know that I had been told about her dad’s wartime heroics, or how I had reacted to the Dam Busters as an adolescent long before meeting her, or how twisted my obsessed and single-sex educated thoughts could be.

I met Britt at around the same time, maybe a little later, selling Greek icons door-to-door in South London. We were both selling these fake pieces of art with some reserve. They weren’t home made by a hippy like Kathy Cruise, who had created herself the candles I had sold door-to-door in Edmonton a couple of years before. A businessman was simply selling repackaged art for a tackily high price. The chintzy icons, small prints of famous works of art glued to pieces of varnished wood, did look good. I kept one for many years as a memento

Pete Coleman, a marvelous salesman, was our team leader and inspiration, all smiles and cockney good humor, and he helped both of us surmount our worries about selling people things that they did not need. “No harm was done,” he would encourage us, “they’ll waste their money somewhere else if they don’t give it to you.” My buyers mostly wanted to chat, and having initially refused the icons, offered to buy one or two at the end of our conversation, perhaps over a cup of tea. Normally relishing the change of heart and completing the sale, a few times I would just leave if I felt that the would-be buyer couldn’t afford it.

Britt and I somehow started dating a little. Not a lot, and I’m not sure looking back how we did so. I was living in Marlow, driving or thumbing back and forth to work in London most days, and she lived with her dad and stepmother in a luxurious apartment not far from Paddington Station. I was 19, and Britt was only 17. Her dad was South American, I thought, and it was understood that she could not have a boyfriend, let alone have a boyfriend over. That did calm the savage breast!

Calmed it, but not controlled it! She invited me over to her place one time, her dad’s place, when we were getting hot and heavy and looking for privacy and comfort. She convinced me to come in by assuring me that her dad never walked the hall from the salon to her bedroom. He did that evening! I cowered under her bed trying desperately not to breathe heavily: we had been making out when we heard him coming. He would surely have taken a dim view of any lout under his daughter’s bed. That was the last time I visited her home! And not long after her mother took her back to Colombia to stay with her.

We wrote, Britt more than I to be honest, in an attempt to keep things going, but long distance didn’t work for me. I invited her to meet up in Miami, which seemed a doable half way point for both of us, but she couldn’t make that because of the cost. As we each moved on, Britt remained friends with mum.

In early 1973, Paul Newman of Bracknell gave me a dream job delivering caravans. He had upgraded a Ford Transit flatbed with a V-6 engine in place of the factory four cylinder, and had found a used trailer that it could pull. His idea was to deliver three caravans at a time, one on the flatbed and two on the trailer, with lower running costs because the Transit, a small commercial van, cost much less than an articulated lorry (the English phrase for tractor-trailer) to run and carried the same number of caravans. And because I did not have the HGV (or “heavy goods vehicle”) license required to drive these lorries, I was cheaper than a driver who did. He paid me 45 pounds a week for an expected 60 hours of work. It was good deal for both of us. He was paying much less than he normally would have, and I was delighted to have the opportunity to drive long-haul before I turned 21, the minimum age for an HGV license.

The job worked wonders for me, if not for Paul. My first trip began with a pick-up of three caravans from their manufacturer near Dover in Kent. The whole rig was almost sixty foot long, and loaded was an impressive if quirky sight: I felt great at the wheel, for about half an hour. That’s when the Transit began having trouble hauling this full load. The clutch burned out crossing London, after 70 miles of what would be a 500-mile trip. Paul may have miscalculated somewhere. But we kept it up, delivering quite a few caravans with only a couple more breakdowns, for three months.

Joanne was from Marlow, and lovely in that dark and smoky kind of way that is somehow not English. She was a gypsy in a Wycombe High School uniform, the uniform of my sister’s school. Her hair seemed difficult to style, wild hair framing sad dark eyes. A girl like her in full bloom, “en pleine fleur” as the French say, is over the head of most adolescent boys, destined as she is for young men years older with improved personal hygiene and fewer spots on their faces.

As that is the way things are, adolescent boys let the feelings go without undue regret. That’s how she was for me, before Paul Newman gave me that job delivering caravans.

Joanne had started at Newcastle University, and I had a two-caravan delivery to make that took me through Newcastle. She was still way over my head, but my travels had reassured me that a beautiful girl was not necessarily entirely out of reach. I paid her an impromptu visit, very casual of course, “just passing through, thought I’d stop by to say hi.” She too was actually welcoming, again to my great surprise, obviously pleased to see me. Perhaps she was simply flattered by a long-distance visit from a not-so-secret admirer. Perhaps seeing me away from her home allowed her to be more friendly than if she had been around her older brother, who was at school with me in Marlow. I didn’t know why the visit seemed to be working, but it didn’t matter. What mattered with my limited adolescent emotional vocabulary was that we chatted well and easily. I was approaching her as gently as I could, so conscious of how lovely she was, of her figure camouflaged in mid-week casual clothes. I can still see the shape of her face that evening, the burning and smoky eyes.

From the window of her dorm room, we looked out on a dark and damp winter. The street lights glistened below in the rain, and their lights and the lights in the other buildings across the road and across the city framed the moving lights of the cars on their stop-start way across town. The patterns of lights in that urban darkness, some still and flickering, some moving and flashing, was the backdrop to her acceptance of my first tentative caresses, across her back, along her arm. I kissed her, and it was as difficult a step to take as my first ever kiss. I glanced down as she watched me with those nervous doe eyes, and remember the flash of her blouse in disarray, the glimpse of bra and breasts, as clearly as if it was today.

I left too soon, perhaps, this time because I was the dutiful employee driving the caravans out of town before I slept in one of them, to protect them from thieves. Again, I wasn’t ready on this first visit to spend any more time with her, not that evening. That girls take time to be ready for romance is well understood. That boys take time too is not. We are simply so flagrant in our desire in those initial post-puberty years that the desire obscures everything. I wasn’t ready: the desire that flooded me was all too powerful for my fragile spirit and skinny frame, and I ducked it. I still felt great. We would get together another time, and it would work out. The groundwork had been laid.

But somehow, yet again, the follow-up never happened. I don’t know why. Was I too slow or too fast in following up? Did she think about the wisdom of starting something with a van-driving drop-out with an almost anti-English penchant for the US (many in the UK felt that liking Americans was not being properly English)? Did she talk to her older brother or one of his friends, and find someone who had bad-mouthed me? That possibility worried me a lot. Did she feel rejected by my leaving prematurely that first night, or confused by it? The only stupid mistake that I am aware of is addressing a letter to her using the wrong last name, calling her Joanne Woodward, dumb but obviously inadvertent. After all, I was working for Paul Newman!

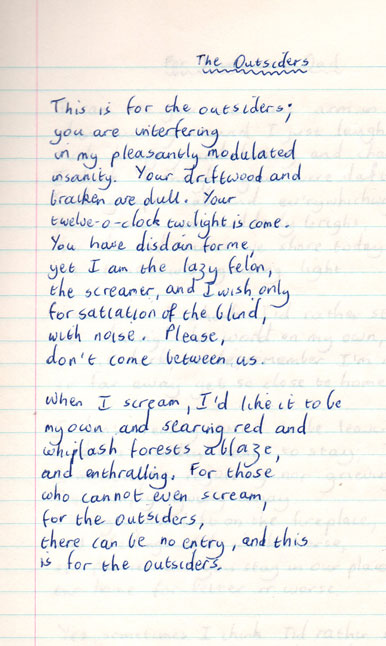

I was exploring writing lyrics in my spare time, mostly verses of staccato syllables which did not mean very much but sounded suitably virulent. They were the written version of my daily bristling in response to real or imagined slights. I ended up writing an adolescent lyric for Jo. It was an angry and vindictive little monologue berating her for ignoring me, but had a pleasing punch line that I fancied to be Dylanesque: “just bear in mind that though this was written, it wasn’t written for you.” Needless to say, I was rather proud of my modest literary efforts, their illogic proving that the emotional denial was false. At the time, the hurt was raw and the whole thing made no sense at all. It was years before I realized that I was acting out Neil Young’s lines: “Down by the River, I shot my baby, . . . shot her dead.” Did Jo notice? Did she even care? I doubt it.

Driving south from Newcastle the morning after that poignant visit, a car overtook the rig on a four-lane stretch of the A1. Its driver and passengers were gawking and pointing, alternately at me and back at the trailer, and laughing their heads off. I was wondering whether the unusual configuration of Transit flatbed and trailer looked that funny, and just in case thoroughly checking the rear-view mirrors. It turned out that they were not needed. Out of the side window of the cab, I suddenly caught a glimpse of a wheel rolling along next to the van at about 60mph. It stayed on a parallel course for a while, as I watched horrified, before angling across the two lanes going the other direction and off into a ditch. Fortunately, it missed the cars driving the other way, but must have given one or two drivers about as much of a shock as it gave me. It seemed to roll along that dual carriageway forever. I pulled over on to the side of the road as fast as I could, jumped out of the cab and ran back to examine the trailer’s underside. Sure enough, the wheel had literally fallen off the trailer, at speed.

Fixing this breakdown was more of a challenge than the burned-out clutch, because it took a welder to reattach the wheel to its axle. The trailer had two axles, and when that wheel detached itself from one, the other fortunately held. I didn’t want to push my luck by driving the loaded trailer to a welder, and so needed to locate one able and willing to come to me on the side of the A1. It took a while. The welder who finally drove out with his torch and gas tanks was suitably impressed that the trailer’s axles had held. I had avoided an accident, but even with the lacunae that characterize the perceptions of a 20 year-old, was beginning to worry.

When the accident finally happened, it was minor and squarely my fault. Paul had even picked this occasion to be in the Transit’s passenger seat. I was driving three caravans near Bracknell, where he was based, and turning left from a lane on to a major road at a T-junction. The rear caravan overhung the back of the trailer by several feet, and the wheels of the trailer were at its middle rather than at its back as they would have been on a fifth-wheel trailer. So the whole rear swung out on corners even if there was no caravan overhanging. Pulling out of this narrow lane, Paul was telling me to stay on the wrong side of the major road. As there were cars coming toward us, I ignored his advice and steered quickly onto our side of the road, forcing the overhanging caravan to swing abruptly out at the corner. It thwacked the country lane’s hedgerow, which ran out almost to the edge of the main road. While not a serious accident, the hedge caused the overhanging caravan some damage, and Paul said that at least a portion of it would not be covered by insurance. Shortly after, he told me that he was going to be taking over the driving himself, to reduce costs.

That was the end of my dream job, but not of Joanne. When things didn’t work out with a girl, I tended to cling in one way or another, just as with Terry in Canada. In Jo’s case, I skulked around outside her home from time to time in the evening, secretly hoping for contact, but mostly just waiting and watching. I kept myself well hidden, embarrassed by my longing, and ended up spending another unexpected evening in her company, on the street outside her family home in Marlow.

Having parked dad’s Granada somewhere out of sight up a side street, I wandered casually around the corner to take up a position somewhere in the trees and bushes across the frontage road from her home, and then jerked back into the shadows when I saw her. I wasn’t sure at first that it was Jo. There were two silhouettes in a car parked on the frontage road right in front of her house, kissing by the surprisingly bright light of the nearby street lamp. As I watched, the kissing went on forever, and was so terribly, forcefully passionate. Their mouths clung together or separated to breathe and pant as she threw her head back with her eyes clamped closed. I recognized Jo’s face during one of those breaks, but had already decided that it was her. They writhed together on the front seat of the car, and I moved around urgently outside, sneaking up and down the bushes that shielded me from their view, trying to see more, torn between the desire to watch her and the need to flee.

She was learning to love as a young woman learns, but what I was learning was frankly a little odd. It felt keenly sad, yet still somehow exciting, shaking and trembling exciting, all at once. I could not be with her, but for that one evening at least had found some perverse sort of substitute. After about twenty minutes of unintended performance, Joanne abruptly climbed out of the car and walked briskly to her front door with barely a backward glance. Did she come too close to letting him go too far? Was that the cause of her abrupt departure? Had they gone as far as she wanted? The answer did not seem that significant. I crawled off into a hole somewhere to lick my wounds.

Not much changed after the drama that inadvertently played itself out under a street lamp in the middle of my foggy adolescent angst. Except that in the future, my feelings of jealousy included that voyeuristic element. The angst continued to attach itself to one or another of the girls I was attracted to. Why it attached or detached was a mystery to me at least, and perhaps to everybody concerned. Obsessive angst, even mildly obsessive angst, is not based on any kind of logic.