(from “Born to be Wild,” written by Mars Bonfire and performed by Steppenwolf)

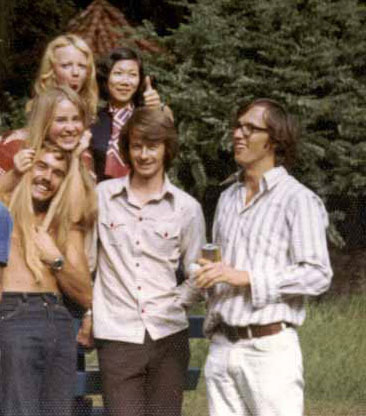

Here’s a great illustration of the relationship between rock’n’rollers and life on the road. The band is the very same band whose song I used to sing heading out on the highway, Steppenwolf, and when they left on a trip in 1971, they left in their very own private jet! Not that I begrudge them: but it was clearly easier to sing it than live it. This photo is © John Kay, he of the howl, and Steppenwolf.

Rock musicians love to sing about life on the road. Each makes it sound as if he spends much of his time thumbing around, hitching from city to city with his drum set on his back. I say “he” advisedly: you don’t hear much of women rockers singing about thumbing around.

Well, as someone who spent a fair bit of time on the road, I never did see one professional musician there. A rock musician can afford way better as soon as he becomes even a little known. So for him, the songs are not likely to be memories or historical portraits. Rather, they are expressions of desire and fantasy, of romance and escape.

For me, for a while after leaving Borlase’s, those songs were real. Standing on the freeway on-ramp or walking along the side of the highway, thumb outstretched, I could hear as if coming from afar the pounding beat of Steppenwolf howling: “Get your motor running, head out on the highway, looking for adventure and whatever comes our way. . . Like a true nature’s child, we were born, born to be wild, we can climb so high, I never wanna die!” (From “Born to be Wild,” written by Mars Bonfire and performed by Steppenwolf). It is one of the songs that made rock’n’roll what it is, and it was my favorite road song. I couldn’t sing it: I never could sing to save my life. But I could hear it pealing like a bell in my head time after time, effortlessly.

I spent month after month on and off the road, and when I was on I was really on it, hair parted in the middle dangling down the sides of my head, staring down the traffic with my arm up and my thumb out, a heavy backpack resting on the tarmac next to me and that portable Sanyo radio-cassette player close by so that I was never too far from the real music. Being on the road was just me and the weather, me and the scenery, me and the traffic roaring by, me and the drivers I met. I changed Steppenwolf’s lyrics in my head every time I sang their song: “hitching on the run-in, head out on the highway . . .“.

David and Pam Warrington with dad in the back garden during a visit to Marlow in 1970. Perhaps this visit gave me the courage to arrive on their doorstep in Vancouver. We were not particularly close, and didn’t see each other often.

I wasn’t looking for adventure, either, although the words felt good to sing and at times it was a real adventure. I was looking for something vague and difficult to define, something like an escape from the run of the mill life I’d been raised to live, or a sense of community, a community where things felt right, or at least okay, or a more complete picture of the world we live in than the one I’d learned in school. I was looking for a sense of belonging to fight off the incredible loneliness, or more simply a different kind of love from the narrow and sordid kind I had found. I was looking for the music to be real.

Plus, I needed to get away from something, maybe boarding, maybe being a late developer, maybe the dirt and the grey rain of post-industrial Birmingham. Who knows? In “The Wild One” Marlon Brando was asked what he was rebelling against. “What have you got?” he sneered. I don’t think that I sneered (maybe I did), but I argued against pretty much everything that I thought the older generation took for granted. I thumbed all over the place, and wore hippy clothes, like my long-time favorite, a US army jacket with trainee epaulettes, and smoked a lot and drank a little, and definitely did anything but what my parents and teachers wanted me to do. I felt very little rancor. It just so happened that I was doing the opposite of what they hoped and dreamt for me.

I didn’t take this one myself: it was on the internet in 2008. The signs looked something like that when I travelled this road.

I didn’t think about what I was doing in philosophic terms, or at least that was not a day-to-day preoccupation. I thought about where to thumb so that a car could stop easily without becoming a traffic hazard, because then the driver would be more likely to stop. I thought about whether to walk along the road with my back to the cars passing by, so I could feel and see the way forward, or to stop and face the drivers I was soliciting. I thought about which would be the next town to stop in and visit, and where the next meal was coming from. I thought about the endless pine forests of North Ontario going on and on and on, the Rogers Pass climbing over the Rocky Mountains, and the enormous canopy of milky sky in the Canadian Prairies. I thought about whether you could tell how far away the next town was at night by the halo of light above it in the prairie sky. I thought about the next town or the last town or the town I was driving through. All were possibilities. I thought a lot about possibilities, and I thought a lot about how to keep warm and about why I didn’t have warm enough clothes.

That was easy to answer. Like many of the wonderful things in life, my first real trip on the road was unplanned, almost an accident. I owe it to US Immigration in Albany, New York. The plan that I had developed at the Roys’ house in Cambridge was to go visit Lance Bentley’s friends in Alhambra, California. It wasn’t quite clear how I would get out there, but it was clear that I would first need to earn and save some money. A cheap old car would have been easy to find in Cambridge. But when I conscientiously called the office of US Immigration in Albany, to ask for permission to accept a job that Paul Roy had found for me, washing dishes in a diner or something similar, they told me to come down to their office. Once there, the immigration officers brusquely informed me that by looking for work I had demonstrated the intention to change my immigration status from visitor to permanent resident. They concluded by requiring me to leave the country within five days. I couldn’t believe it: first they trick me into coming into their office, and once there the mere intention to do something, expressed by asking permission to do it, was a punishable act. The officers concerned wanted me to be grateful that they weren’t going to deport me, and I suppose I was.

Rather than being obliged to fly home by stupid bureaucrats, I could go to Canada instead. If I couldn’t drive some old car out to California, I could visit my cousin Dave Warrington and his wife Pam. They had emigrated to Vancouver BC not that long ago. Vancouver was on the Pacific Ocean, well almost, and in any event was a lot closer to California than the East Coast. I did not have enough money to pay even the bus fare out to British Columbia, and US Immigration had only given me five days to leave the country. It wasn’t hard to figure out the next step. I’d thumbed around Marlow after all, around Greater London even. The Roys drove me up the Adirondack Northway through Lake George, past Plattsburgh where John Paul, their older son, attended college, and across the border, dropping me outside Montreal in the evening of the fourth day of the five that US Immigration had given me to leave the US. I was so sad, watching their rear lights dim in the drizzle as they drove away. Finally, I had what I wanted somewhere: I was on my own.

This is Francis Brennerman with his truck on the Trans Canada Highway somewhere around the Ontario – Manitoba border. Francis picked me up outside of Thunder Bay and drove about 400 miles west at 40 mph. Thank you very much, Francis, the first of my miracle rides to Vancouver. I am embarrassed to report that the slow pace of the ride drove me crazy. I kept thinking to myself that I would have made quicker progress if I had waited for one of the many faster cars who overtook us.

They dropped me on an on-ramp to the Trans Canada Highway, 3,000 miles and one highway away from Vancouver. The last segment of the Trans Canada, over the Rogers Pass, had been paved as recently as 1963. As an entirety, the road was only seven years old. It was fall in Canada. I was dressed in English winter clothes, with a dark blue RAF greatcoat (not a fleece-lined bomber jacket) as the warm layer. It was nothing like warm enough, even when I started out in early fall. The weather started off drizzly in places, windy in others. And Vancouver was a little further than I realized. The first night rolled slowly on, thumbing first through Ottawa and on towards what the Canadians call North Ontario. The Trans-Canada Highway crosses thousands of square miles of pine trees and circles hundreds of miles around the top of Lake Superior, one of the Great Lakes and a veritable inland sea, from Sault Sainte Marie to Thunder Bay. One ride at a time, I travelled around the lake on the second day away from Cambridge.

I hadn’t slept properly, of course, and arrived west of Thunder Bay late that night. Nothing but the occasional semi-trailer was on the highway this late, and even the trucks were few and far between. To ward off the cold between trucks, I crawled into my sleeping bag on the side of the road, and jumped out to stand and thumb as one approached. Big trucks rarely picked up hitch-hikers, I found out later, because of insurance risks or because the shipping conglomerates that owned and operated many of the trucks did not allow it. But sometimes they did. I jumped out of the sleeping bag several times in the first hour and then, much to my surprise the next morning, fell asleep. A horn blaring and guffawing woke me up as dawn spread over the sky. I was laying perpendicular to the traffic going by, and my head was about two feet from the white line marking the edge of this two-lane highway.

So my continuing presence on this earth is attributable to the careful driving of the truckers who drove west out of Thunder Bay and past me that October night in 1970. It takes a while to master any skill, and until you do there is risk. The same applies to thumbing. Thank you, that night’s truckers, whoever and wherever you may be. I barely thanked them at the time, first because I wanted a ride and in the biting cold of the Lakehead the fact that I didn’t get one seemed much more important than the fortuitous diligence of the drivers who had not picked me up. In any event, I felt immortal, as I suppose must most young people as they come of age. It was a kind of certainty. I’d listen to The Who singing about “My generation:” “Hope I die before I get old” (written by Pete Townsend, and performed by the Who). Did I agree? Not really. I was never going to die. Such questions were pointless. That I remained alive and well despite the many stupid things I did was preordained. I didn’t need to be grateful, or feel lucky, or thank God. I was young, and cocky, and on my way.

This is the guy who drove me from Oak Lake, Manitoba to Lethbridge, Alberta, a very long ride. I’m afraid I didn’t note his name at the time. He was a traveling salesman.

All told, that first long trip west took only about three and a half days. The last two miraculous rides took me about 1,400 miles from Oak Lake, west of Winnipeg, Manitoba, where I slept a couple of hours in a church that had been kindly left open, if unheated, to Lethbridge, Alberta, and then from Lethbridge all the way to Vancouver. I kept pace with the Greyhound bus! I was running to get somewhere safe; in a way I was running away from being on the road and from the unknown. It is scary when you first do it. No, it’s always scary. You learn how to manage it with little tricks, like looking for a place to stay when it’s still daylight, or favoring college towns because students tend to be nicer. But it was a big world: Canada is about as big as you can find in the industrialized West. There were no cell phones, and I had no defense of any kind if one of the world’s meanies stumbled upon me here.

By the time I headed back on the road, a month later, I was ready for it. The trip back East started in Vancouver on November 6, 1970. I had tried to thumb South to California, but had been turned back at the US border. I had looked for work in Vancouver, both staying with Dave and Pam Warrington and later while living in a hostel courtesy of Children’s Aid, the local social services agency for children, on West Broadway. Nothing came of the job-hunting, and Canada had the same approach as the US to preserving its jobs for its own people. That made sense. Canada felt more compassionate as a government than US Immigration in Albany – witness the free housing offered transient children for a few weeks – but I wasn’t about to take too many chances. Once bitten, twice shy. I was heading back East to see if there was any work on the way, and if not at least I’d be better situated to return home to England. That is where I ended up five weeks later. That was all, five weeks.

Vancouver, BC. October 1970. I had a camera with me, but unfortunately ran out of film soon after leaving Vancouver and could not afford to replace it.

I wrote a journal of that trip, and mum held on to it, even had it typed up. I found it among her papers after she died in 1996. Only one of the original 88 pages is missing. It is entirely hand-written, single-spaced, broken up into sections of the trip, and the handwriting is relatively neat and clear. It is a treasure trove of impressions, job-hunting observations (but very little actual job hunting), youthful bullshit (I really was full of it!), anecdotes and hidden feelings. It was the only journal I ever kept with any degree of commitment. There are moments of real lucidity, others that surprise, and a whole bunch that make almost no sense. I made a few calculations after arriving home, and noted them at the bottom of the last page: 7,610 miles in all: by plane, 2115 miles; by boat, 95 miles; by bus, 350 miles; and by thumb, 5050 miles. Now that was a trip to write home about!

Rereading the Journal now gives me a strange sensation, a window, however opaque, into another lifetime, another Ian. I don’t like him very much, this 17 year-old Ian. There is a lot that confuses me. I was way too brusque and dismissive and intellectual back then. Here is a description of a group of young people hanging out in Calgary: “At R & J’s they all seem to live their own selfish inhibited lives indulging in everything to excess, everything that is that pleases them and are because of this symbolic and a part of a very confused and unstable society that is north america (sic).” My guess is that I didn’t feel too comfortable there, but it’s the sloppy social commentary poured down from above that I put down on paper, mixed with the bad grammar. Or again in Montreal, describing an afternoon with new-found friends: “Any moments of interest were caused solely as breaks in the dreariness. For example, a quick game of soccer out in the street was the highlight of the afternoon, despite the ineptitude and classic lack of brilliance of their soccer.”

Who did I think I was! I barely knew these people, my hosts in a strange city who were feeding me, lodging me, even kissing me on occasion, and yet I take the trouble to put them down in petty and niggling ways. There are similar moments of appreciation in the Journal, of course, but those appreciations too were offered from on high, where I sat in judgment. I had not remembered putting people down so much at that age, or being seated so far above others. The written portrait of the Journal feels more distant from the modern me than most of my memories unaided by a journal. Unfortunately, I doubt that the writing corrupted who I was. Rather, in this case I suspect that the Journal reveals what memory does not want to retain.

That’s me, second from right. I have no memory of this day, but apparently accompanied Dave and Pam and their friends to Vancouver’s Stanley Park. Pam is sticking her tongue out above my right shoulder.

The memories that have stayed with me across the years were not necessarily written down. I started by crossing the mountains to Calgary, 690 miles covered in 22 hours, the Journal announces tersely. I remember it started snowing as I was crossing the mountain ranges of British Columbia, the most Easterly of which are the Rockies. My memory is of the beautiful sight of snowflakes in the halo of a streetlight at the edge of Golden. Towns on the Trans-Canada Highway often had a series of gas stations and cafés or diners right before the open road, and Golden followed this rule. The best place to thumb at night in such towns was as close to the open road as possible, but still in the light from the street lamps. That way, you were convenient to stop for if anyone was setting out on a journey where company might be a plus, and visible. The drivers are not yet at speed, also improving your visibility. I stood for hours that night, just past the row of roadside businesses, watching the snowflakes dancing and racing into and out of the light of that one streetlamp, the last before the darkness of the highway and the mountains. I was mesmerized, and look forward to this day to any occasion when I can watch the snow fall in the quiet and dark of an open highway at night.

In the Journal, I first griped about the “stony reception” that had “greeted me” at the Husky gas station café, and then complained about how cold it was waiting four and a half hours for a ride in the snow. That all sounds true, but was only half the story. It is pure luck that in this particular case I actually retain the memory that fills out or balances the Journal. My guess is that in most other cases, what was not written down has simply gone. If I only knew.

The Journal gives a framework, and invaluable (to me) information that in its absence would have been lost. But it was unwittingly edited as I wrote it to give various messages. One was something to do with how hippies like me were discriminated against and required to suffer in silence. That was a strong feeling throughout that lonely trip, but a little deluded. We who were on the road certainly did not suffer as black or Jewish people have suffered, for example, and in a way we chose to suffer the limited amount that we did. Or the Journal focused on events that struck me as important to tell my parents about, another kind of slanting of the communication. I was writing to my parents, and suppose that such a slant was inevitable, but it means that I can’t simply paste extracts of the Journal here.

The top half of first page of the Journal, a little worn by the 38 years that have passed since it was written. I added the capital letters on top after arriving home. “Incredibility!”

The most perplexing differences between the Journal and my memory are the memorable events described in writing but which I have no memory of. The ride out of Golden in the middle of the night was with a transient cook on his way to his current assignment, cooking for construction workers at the Mica Dam project on the Revelstoke River in British Columbia. That sounds right. But in the Journal I complain about being awakened by his car spinning around three times on the damp ice of the highway. Shouldn’t I have remembered that? I don’t. Isn’t that the kind of sensation that should be pretty much unforgettable? Or again, between Calgary and Edmonton, the next stage of the journey, a couple driving a car with no brakes gave me a ride. That feels familiar, and jogs some sort of memory. But did we really drive three times past the pumps at 5 mph at the gas station where they stopped to buy gas, as I wrote in the Journal? Shouldn’t I have remembered such a good comic moment? Or did I construct it out of a little difficulty lining up at the pump?

Part of a letter that Sue sent me in Vancouver. Mum held onto it. My “little girl” is Honey, the pretty tortoiseshell cat, who demonstrated reassuringly that she missed me whenever I traveled. Here, she broke her normal rules and permitted other family members to stroke her. Touching.

I can’t really tell, but do think it is possible that I dramatized some of what happened to make it more interesting, to make me more interesting. I remember inventing alternative backgrounds and biographies for myself during that trip and with other drivers who picked me up hitch-hiking. I don’t remember any details, but the moral position of such fabulating worried me each time that I did it, until the next time! During that month living in Vancouver I even gave most of the new people I met a name that was not mine: I think it was “Peter,” using my oldest cousin’s name. Was the purpose of the fabulating and the name change a kind of self-dramatization? I don’t think so. The drama was a sidebar, I think. Or was I just hiding from something? Again, I don’t think so. Not a lot to hide from. Did I want to be a different person? Yes, maybe, that’s the one. Once I left the Roys in upstate New York, I was as far away from my roots as I had ever been, and perhaps profited from that distance to attempt a more drastic change in who I was. I was not too happy with the real me, that was for sure. The new me would be drawn on as clean a slate as possible, beginning with various new biographies and a new name. Nothing fancy, no melodrama here: just bye-bye Ian.

Not particularly photogenic, is it? Fog on the freezing prairie, outside of Edmonton on the road east toward Saskatoon. The sky was a little yellower than the ground. Winter was on its way. This was almost the last photo that I took on this trip: ran out of film.

I apparently did not feel particularly welcome in Calgary, and thus wrote more than a few nasty things about it in the Journal, even though I was driven out of town by a hippie in a Lamborghini. Edmonton attracted more favorable reviews. Edmonton is a couple of hundred miles due North of Calgary, by the way. I was not trying to follow the fastest route east. I stayed there a couple of days with two students at the University of Alberta, Alan Brewster and Liam McCaughty, after meeting Alan in a Dairy Queen right after I arrived. They were both very stimulating company, and had studied with passion James Joyce’s literature, which they lived to discuss. They lived for the constant cups of tea, too, and word games.

Now there’s an odd connection. It is not written in the Journal, but I remember one of them quoting a Joyce question that went something like: “who gave you that numb?” explaining that Joyce meant that a name was a numbing blow from which one never recovers. I’m not sure that I understand what Joyce meant, even forty years later, unless we’re dealing with Johnny Cash’s “A Boy named Sue” or something similar. But wasn’t I escaping from that numbing blow by changing my name? The only fault with Ian as a name appears to be its brevity, but perhaps the baggage attached to the name has its own effects, and perhaps by changing my name I was unconsciously seeking escape from those effects. The strange intermingling of truth and fiction in the Journal may have brought its own kind of liberty, as did my own fictitious name.

Needless to say, I was far from free of the still disorienting effects of girls, and this too creates its own kind of editing of the Journal. Thumbing across Canada was an escape from many things, but not from girls. Some of them were so enticing, even in the world of the street that I was travelling through, the world with little make-up or fancy clothes, that I just could not escape from them however much I tried. And I’m not sure I tried that much either! Or rather when I did try to escape them, it was doomed to failure. Just because the whole subject was difficult, problematic even, did not mean that the subject was closed: far from it.

On this trip I spent a couple of weeks meandering around the Province of Quebec, from Rouyn-Noranda to Chicoutimi, as well as in Montreal and Quebec City, the province’s heart and soul, and I did so in large part because of girls. That is barely visible in the Journal. Of course, I mentioned finding Nicole Boulanger in Rouyn, and that it was good to see her, but not that the principal reason I was there and had followed a northern backwater of the Trans Canada Highway across half of Ontario to get there was because I had a mad crush on her and fantasized constantly about her slim hips and insouciant posture. I didn’t mention how disappointed I was that she kept me effortlessly at bay when I did find her, as a “friend,” or how unflattering it felt to be shown to her friends as a kind of trophy, the English guy who came all the way from Vancouver to visit.

Likewise, I never did find Susan Gravel, the radical Québecoise I had briefly dated in Vancouver. Emphasis on “briefly:” we had one date. She had a big, dark and bearded boyfriend, and snuck away from him into my arms. She was my one fling in Vancouver, and had made me feel great just by being interested in me. Not being able to locate her hurt at the time, and looking for her all over permeated the days in Chicoutimi. I was convinced that she was there and avoiding me. These feelings still lurk in dark recesses until this day, but they don’t appear in the Journal at all.

Some of the people staying with me on West Broadway courtesy of Children’s Aid. The “house mother,” the only adult, is on the left at the back. Nicole is leaning on the banister in front of her. She was witness to a shooting involving her boyfriend, if the Journal speaks the truth.

On the road, I could simply move on. I did simply move on. That was part of the essence of being on the road. Bad feelings come up everywhere, in fact. When you’re stuck in a school or a job or a small town or a big city neighborhood, getting out or away becomes a kind of dream, a cure-all, a panacea.

Ultimately, no amount of moving on will cure what is inside you or what characterizes your world. But on the road you can avoid recognizing that distressing reality, and thumb to the next town that catches your fancy or to the next person you are looking up. You’re distracted and interested again, until the next bad feeling or the next major event knocks you off your feet again, and then you can always leave, and you do always leave. On the road again.

That may be why I stayed on the road, on and off, for so long, and kept moving from city to city for years later. It was a way of assuaging the almost constant aching that plagued me, that lodged itself inside me and tugged at my heartstrings again and again until it almost became the norm. It wasn’t just girls or social ineptitude. During my teenage years, the aching had gone from an occasional feeling with a fairly precise focus to a habit and a way of being, a way of being that hurt almost all the time. By the age of seventeen I could barely eat I ached so much. Moving on didn’t cure the aching, but it did ease it, until the next time. That was good enough for me. It wasn’t a chemical cure, and it wasn’t some dumb creed or belief system. I already had little patience for such dreams or diversions. But I needed some kind of relief from the aching, and found it on the road.

This trip east was rugged, hard. It was substantially longer in distance than the trip west, continuing east for 1,500 miles after Montreal, and that is if you take the direct route which of course I didn’t. It was substantially longer in time, five weeks as opposed to a few days on the way to Vancouver. Also, it was now winter in Canada, a country limited and defined by its winters, and it felt a whole lot colder. I had no new warm clothes. It was a kind of marathon, an endurance test for which I was inadequately equipped. I had no money at all most of the time. On the way out west, I still had the dregs of my savings from working in Marlow before the trip. Having found no work in Vancouver, I had none left. Dave and Pam were pretty short themselves, even as immigrants entitled to work there, and I didn’t want to ask them. Dave’s father, Uncle Alec, had already been dead a few years, and Dave was really on his own. I might possibly have been able to ask mum and dad, but the thought of doing so made me very nervous. I don’t really know why. There was always the possibility that they might refuse, to point out that hitch-hiking to Vancouver in the first place lacked a certain intelligence as a plan. I couldn’t argue with that! Secretly, I dreaded their refusing me. In any event, I didn’t want to ask for what I should have been able to earn myself.

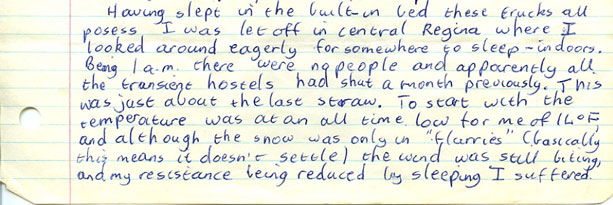

Another segment of the Journal, this one covering the journey across Regina, Saskatchewan on the way back East. It was bitter cold. I was in a bit of a panic until the next ride. But when it came, they took me all the way to Thunder Bay, around 800 miles. Thumbing was often like that, highs and lows intermingled.

I should not have attempted the trip. Being broke, when I wasn’t looking for a place to stay, I spent a fair bit of available time focusing on eating. Food was frequently harder to locate than a place to stay. There are many mentions in the Journal of this process of taking care of the basics. I don’t know that scarcity breeds want, because want seems to happen easily without any scarcity at all, but scarcity does breed a focus bordering on obsession. The effects of having no money took me by surprise, oddly enough. It would appear to be an easily foreseeable logical consequence, but I only really saw it when I got hungry. Each time!

To quote segments of just a few days in the Journal, starting with Fredericton, New Brunswick, where “a VW picked me up. It contained a 25 year-old, vivacious, well-dressed bloke, who decided I needed breakfast. . . . I was promptly given eggs, bacon, four pieces of toast and honey and good strong tea.” In Halifax, Nova Scotia, a student “calling me ‘limey’ much more often than was necessary . . . gave me a hot dog and a glass of milk, which was appreciated in the spirit it was meant.” In Antigonish, Nova Scotia, “they then forced a massive much appreciated supper on me, a supper of three meaty hamburgers, a bowl of hashed potatoes, bread, cherry pie and cake.” Again in Antigonish, the “youngish manager of the local cinema said he would give me $2 for doing some cleaning. . . I indulged in a cheeseburger, French fries and pie, relieving me of a dollar.”

Hunger is never far away when you have no money. The cold and the hunger became central to my life during that trip east. Of course, I was never even close to freezing or starving, but each felt like it could have happened almost any day in that protracted wilderness. 4,500 hundred miles of road in all, 4,000 miles of almost nothing at all. I should add that I was never really worried, partly because of that terrifying lack of foresight which characterizes adolescence, and partly because Canada is full of big-hearted people, understanding and tolerant people. I could be extremely cold and starving hungry, but those were the extent of my worries. However cold it was, however hungry I was, Canadians were always there, close by and willing to listen if I needed help. It may have been dumb luck, but I picked the right place to be broke, hungry and cold.

This is some of dad’s portion of a letter sent to me in Vancouver. He had earlier criticized me for not taking job-hunting seriously. Then Mrs. Roy wrote to let them know that I’d been kicked out of the US after conscientious job-hunting and was on my way to Dave and Pam’s. That worried dad, who knew how far away Vancouver was, and he wrote to assure me that money was available. “I’m not yet completely broke.” I had taken the earlier criticism to heart, and would not take him up on the offer until I’d run out of other options.

For the record, here is an almost random selection of the Canadian people who gave me a ride or fed me during that trip. I didn’t record all of the names of course, especially not the surnames, and have no idea in retrospect why I noted those that I did: Francis Brennerman of Dryden, Ontario; Gerry Clewes of Lethbridge, Alberta; Garry Leier of Regina, Saskatchewan; Kim McEachern of Gander, Newfoundland; Gaitin Plourde of Rouyn, Quebec; Louis Moses of Montreal, Quebec; and William Patrick Shea of Antigonish, Nova Scotia. There were hundreds of others, literally, more every single day, and I thank them all again.

I had learnt how to panhandle in Vancouver, where it was a hobby of those of us staying at the Children’s Aid house on West Broadway, a way that we were cool. Whatever world you’re in, you’ve got to be cool, especially when you’re young. To panhandle, you asked likely looking or friendly people for spare change. A smile helped, and aggression of any kind hindered. A beggar needed to be charming. It was neither reliably remunerative nor comfortable as a pastime. I remember not managing to panhandle enough for even one beer upon occasion, and knowing that I didn’t in any real sense need to be doing it made me feel guilty about it if it went well. I didn’t do it a lot, just as I didn’t do any of the petty thieving that some of my housemates indulged in. On rare occasions panhandling went well. A businessman in a suit and tie came out of what looked like a warehouse in a dubious part of town late one evening. He gave us a crisp five-dollar bill when I panhandled him after Louis refused to ask him for spare change because he looked such an unlikely candidate.

That was my panhandling high-point until I asked a pretty girl for spare change on the main street of Fredericton, New Brunswick. I had finally left Québec, which had been warmer and more hospitable than I deserved, and headed east toward Gander in Newfoundland. Mum and dad had bought me a $135 plane ticket from Gander to Prestwick in Scotland. It was the cheapest regularly scheduled transatlantic flight. As winter fell on the Maritime Provinces, I was heading home, still broke, and occasionally panhandling. I noted in the Journal that I had been picked up by almost no English-speaking Québécois. The kindness I met there, and at times it seemed everywhere, was all French Canadian. Yet a group of radical Québécois kidnapped a British Trade Commissioner named James Cross and then kidnapped and murdered Pierre Laporte, a Quebec government Minister, in October, a month before I thumbed through the province.

I started thumbing in Vancouver and took the plane out of Canada from Gander In Newfoundland, not far from St. John’s, in the far east of the country. This is a continent, the wide part.

As soon as I arrived in Fredericton, I started asking for spare change. It was a good day for panhandling. Terry, from Oromocto, New Brunswick, was my first love. It ended miserably, of course, a year or two later. We never made love. In fact, we never even snogged, or made out as they said in North America, but it was real for me. She occupied my memories and thoughts, not to speak of dreams, for more than a year, and the best part of this first love happened on the road. She was tall, her face above the shoppers on the chilly, grey street where we met. Back in England, every time I heard Manfred Mann sing “Pretty Flamingo” I thought of her, half smiling as she caught my eye and held it. When I asked her for spare change, she laughed that she was about to ask me for the same. That was the reason for the half smile. She was a beautiful brunette, with long slim legs and a face with emotion constantly running across it. Not animated in the sense of relentlessly mobile, but a window on her feelings if you watched and listened. Over the next few days, I did. That was almost all that I did.

That is how I remember our first meeting, and needless to say the Journal disagrees completely. She was stoned when we met, according to the Journal, and told me between giggles that she was a gypsy. She had arrived with another stoner to visit the guy who had offered to put me up for the night. I had met him in the pool hall which was the local hang-out, waited there for him while he went to the movies, and then strolled home with him. He smoked a lot of pot. Oddly enough, I was very impatient with pot and stoners throughout the Journal. Most of the people who were hospitable to me imbibed, and I was surprisingly intolerant of what I felt to be bad habits and the lack of intellect that pot and hash seemed to result in. There are complaints on almost every page, even about being offered to join them! Were these addressed to my parents, who I knew were reading what I wrote? I think so, at least in part. Did I alter how I felt in the Journal to reassure them that I was not in fact a pot-head, or whatever a marijuana smoker was called then? Yes, and I do think that at times I enjoyed sharing what my hosts offered, even if I complained about them behind their backs.

The telegram from dad’s company affiliate in Toronto telling me where to obtain the funds for my ticket home. I picked up the telegram at the Post Office in Québec City, and the bank branch was nearby.

I certainly never complained in the Journal about Jenny getting high, or about the others when she was around. The Journal does show us panhandling together another day, and recounts some of the key memories that I retain. I had no idea at all what was happening when and after we met. Love for me did not mean a lot then, and the closest to romantic love that I had experienced up until then was friendship and desire. They are all related, of course, but had not yet been connected for me. So I glowed inside as soon as we began hanging out together, and wrote in the Journal about how much and easily we talked and how hard it was to remember what we said. I remember that feeling too.

The high point occurred in Whip’s house where I was staying. This is one of those times when my memory and the Journal are almost completely congruent. It could easily be seen as the low point too. Jenny and I had spent the day together, full of the excitement that discovering a kindred spirit, and an attractive kindred spirit at that, can bring. We talked a lot about love, other people’s, which was I suspect our way of recognizing that love was in the air even if we didn’t express it ourselves. She teased me that I would hear about her when I returned to England, but wouldn’t tell me how or why. I wrote in the Journal that “the insatiable curiosity would kill me, I was sure.”

Somehow I guessed during the course of our exchanges and divulgations, and this makes no sense even now, that she had been abused by her father. How did I ever manage to stumble on that? It wasn’t as if there were abused girls in my circle: there had barely been any girls at all. As I spent more time with girls, in Cambridge, New York and since leaving Borlase’s, I was beginning to see serious imbalances between boys and girls when it came to physical intimacy. Boys often made excessive demands, as far as girls were concerned, and for some any demand was excessive. Girls rarely wanted enough, as far as boys were concerned, and never as much as their bodies seemed to us to convey. But there was nothing perverted about this imbalance. You can’t get more perverted than a father having any kind of sexual relations with the girl most entitled to his protection. Wherever did that strange guess come from?

Prompted by the odd accuracy of the guess, Terry lightly conveyed, as if she were describing the weather, that the culprit was her stepfather. He had obliged her from an early age to watch him masturbate and tell him dirty stories. That is according to the Journal. But the Journal was written for my parents, and there was more to tell, but I didn’t want to go that far with them. She seemed so fragile as she glibly told her terrible tale. I felt very flattered that she had told me so much, and very tender. It must have been so difficult to tell. And how awful it must have been to live through. Small wonder that she no longer could stand to go home and described herself as a gypsy. She had no choice.

She took a shower while I watched a documentary about Bolivia, and then came back into my room. She was wearing baggy male pajamas – I can’t imagine where they came from – and sat down next to where I was laying on the bed. Somehow, without trying to peek, I knew for a fact that nothing adorned her perfect body under those baggy pajamas. She did not wear tight clothes, but her figure was the kind that announced itself brazenly even in the loose and shabby jeans, blouses and sweaters that she wore. I was far from immune to her charms.

But the terrible story that she had glibly shared added to the discomfort I always felt around a pretty girl. I was tense and lacked any fluidity, at least for a while. She tried to get through that reserve: perhaps she saw it as English. It almost worked, too, despite all the blockages. We laughed a lot as time went on, and somehow in the middle of a shared laugh I found myself looking down at her on the bed, looking down at her beautiful face, quivering it seemed, at her long, long legs askew in those baggy pajamas, laying next to me, so close, almost underneath me as I smiled down on her. I should have let myself go: it would have been so easy and so right. But the story of her stepfather reared its ugly head, and I didn’t want to inflict something so coarse on her, even though she wasn’t a little girl anymore and I wasn’t a disgusting creep from her mother’s bed. I let the moment go, and I didn’t really understand why, and she didn’t really understand why.

The last page of the Journal, after I made the distance calculations. This page covered the squib from London’s North Circular Road to 18 South View Road.

I saw her again before leaving Fredericton, after searching for her for hours at the different cafés and homes where we’d sat and chatted or just visited together. She was very stoned, and her face was a bit stuck rather than showing the lability that I had been watching like a good movie. I thought I understood, but felt pretty bad about the possibility that I had blown it definitively the day before. Then in the moment of doubt I heard again her promise that I would hear about her when I was back in the UK, and thought to myself that we would certainly have another chance. She must have appreciated my not trying to take advantage of her. It would work itself out in time.

Leaving town I was full of the joy of spring, as the winter’s snow fell. As I travelled on, hope grew that she was intending to visit me in England, that her riddle meant that she would just appear like magic at the front door in Marlow. Rationally I knew that made no sense. She had no money, no real family left to give her any, and no inclination to work any more than she absolutely had to. I would need to return if I wanted to try to work something out with her. How I wanted to!

There’s an openness about being on the move, away from home base, free from your daily limitations and worn-in habits, and out of that openness came a different kind of love. She was pretty as a moving picture, and had already experienced real tragedy; I was painfully sensitive and made a complete mess of the whole thing. So is love made. “You who are on the road must have a code that you can live by. And so become yourself because the past is just a good-bye” (from “Teach your Children,” written by Graham Nash and performed by Crosby Stills & Nash). But becoming yourself takes time, almost a lifetime. The days with Jenny were a step on the way there, but a faltering step.

As I thumbed on across the Maritime Provinces heading for Newfoundland, I did think about whether to return to Fredericton and try to pick up the pieces with her. It seemed too significant a step to take, based on such a short time spent together. I was due to start university soon enough, and had won a good scholarship. So not taking up the university course would end up costing my parents a fortune, and I didn’t seriously consider it. I was still on the track they had started me down, even if rock’n’roll and these trips to North America were sowing the seeds of something very different. I continued on.

My eighteenth birthday began in Sydney, Nova Scotia, and ended across the water in Port aux Basques, Newfoundland. People were very kind, but the Gods were not. The storm that made the 10,000 ton “Ambrose Shea” leave almost four hours late deterred passengers (there were only 12 with a crew of 98, according to the Journal) and made the trip last at least two hours longer than the scheduled six. Passengers and even some crew members were throwing up, and there was no one in the on-board buffet. The buffet staff gave me a full meal for free, because I seemed to be able to hold it down and because they had no other takers for the prepared food. The wind whistled and moaned, the boat rocked and creaked, the snow was a blizzard raging outside on the deck, and I fell asleep, sated, in the lounge. I spent that night in Port aux Basques courtesy of the RCMP, the traditional place to sleep during small town Canadian winter for transients with insufficient resources. I was almost home. All that was left was a flight across the Atlantic, and a few more days of thumbing and bumming.

Thumbing over one and a half times the length of the Trans Canada Highway, the world’s longest national highway, before turning 18, was an unintended escape. I travelled first out of a kind of stubbornness. The US government wasn’t going to send me home just because I broke a dumb rule, even if it was US law. I would remain in North America and complete the trip that I had started and planned to continue until starting my pre-University training in January, even if I couldn’t work and live with the Roys and thumb out to California. I followed that incredible highway so far because Dave Warrington was in Vancouver, because the sheer distance captured my imagination, and because it was not so exotic or foreign as to scare me off. I became addicted to the vast expanses of virgin land that the highway crossed. I fell in love with the Albertan Rocky Mountains, and walking or driving through them knew peace. By the time the trip was done, I was on the road to escaping from industrial England, from the strictures of English schooling, and from the English class system. It was almost magic. Each leg of the journey, each minute of freezing cold, each pang of hunger, was a step away from anomie, from the small-town life in Marlow, from pretty much everything that came before.

Back home, at the breakfast table. Dad took the photo, and cut me almost in half! The ashtray had three monkeys, “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Because of my ulcer, I’m drinking milk instead of the tea that the other three are drinking. Milk and antacid were prescribed, and cigarettes forbidden. Whoops! We were still very tight.

I never had the heart to tell mum and dad to get lost, that they were jerks, that they knew where they could shove it. I never even felt that way. They were so good at letting me go. From the day trip to London train spotting when I was eleven to the trip to Cambridge, New York, at seventeen, they always helped me spread my wings, encouraged me to find my own way. How do you rebel against someone who tells you to go ahead, it’s no problem?

On the road, that’s how. There I managed to move away from the benign influence of that seduction, from the me that they raised and wanted me to be. It wasn’t a bad me, and may even have been a better me than the one I eventually became: it just wasn’t mine. I was moving away from well-meaning parents who sought to orient their children in the mold they felt that they represented. It was our family’s small illustration of the time-honored pattern. Perhaps at times I went too far, for example with the nasty, judgmental arrogance that bothers me now in the Journal. Perhaps the excesses were a means to an end. Ultimately, years later and with a little help from love and rock’n’roll, being on the road enabled this repressed and distressed young man to turn that mysterious corner toward his own future, a future of his own design.

Back home in Marlow on December 11, 1970, my clothes were dirty and worn out, as was I. In the wash, my shirt tore itself right down the back. I kept it in a plastic bag in my closet with the other clothes worn for most of that trip. I rarely had changed them. A persistent if minor duodenal ulcer appeared in testament, the Doctor advised, to the terrible diet that became mine in Canada when I depended on the generosity of others to eat. An equally persistent case of scabies also manifested itself, in testament, the Doctor advised, to prolonged physical contact with someone else who had this particular nasty parasite. There was so little such contact during the entire trip that this particular ailment felt unjust. On the plus side, I had experienced some new kind of love. Terry and I exchanged occasional letters for the next year, building on the note I found from her when I arrived at home. That was the answer to her riddle: it was not her in person whom I would find in Marlow, it was a short letter from her. Nothing fancy. I was so disappointed.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 25 “Can’t Help but Wonder Where I’m Bound”

Previous chapter: Chapter 23 “America”