(from “I can’t Help but Wonder Where I’m Bound,” written and performed by Tom Paxton)

This memoir has been an exercise in constructing my own identity as a child and a teenager from memory and observable evidence. I’ve been working on it on and off for almost five years, mostly off, to be honest. It’s hard for an old dog to learn new tricks. Each time I come back to it, a particular period or feeling reads somehow incorrectly, and I refine it again. It’s time to stop, knowing that next year or the year after I would surely find other stories to add and other misleading slants in the prose. History is at least 90% fiction. Hopefully this is a little bit more accurate.

That’s one of the messages of the Journal that I wrote of the journey from Vancouver to Marlow via Gander and Prestwick. Because of all its inconsistencies, that Journal reaffirms the starting point in this endeavor: knowing even your own past with any degree of truth is well-nigh impossible. If I only knew. The Journal is the only real reality check from my first eighteen years, and it demonstrates vividly how rarely memory coincides with what happened. I obviously wrote it: the whole thing is in my handwriting! But much of the time I find myself exclaiming “what is going on here! What was I thinking?”

The Journal counters the rose-colored glasses of memory and of its absence, and is an authentic text of Ian at a particular point in his life. It is the audible if at times confusing voice of this stranger from the past. It mixes what was hidden or shaped for my parents or even for me and what was this stranger’s honest voice. It illustrates that this memoir would probably read very differently if it benefited from journals throughout the period it covers.

By chance, the Journal covers my coming of age. Coming of age is looking outward, seeking a path or a light. It is breaking with who you were in a complex search for who you can be. It was changing my name in Vancouver for no good reason, fabulating to total strangers as I traveled, and thumbing over 5000 miles in five weeks alone and in the cold as winter fell over Canada. I hope that the arrogance that distressed me in reading the Journal so many years later was a part of making that break, and not an expression of a central part of my character. I’m afraid that it could have been the latter. So be it. How else do you break free? Mum and dad were so understanding and kind that I felt guilty for even wanting to break free.

So I didn’t. Back in England after flying across the Atlantic from Gander, I went almost straight home. 18 South View Road, Marlow, Bucks. was still home. I’d taken a trip lasting three to four months, cutting it fine for three to four months, but I came home. It would be years before I really left. Independence was one aspect of adulthood that was not yet upon me. I was eighteen years old and still with my parents and still content to be there. I had no idea that I was driving them mad with worry. I did know that I was doing less and less of what they would have ideally wanted, but I was still with them.

Dad still called me “Sunshine,” but I ached a lot, I always ached a lot. By this time I called it the need for a good woman when I thought about it, which was terribly often, although I was still a boy. The ache was so strong that it ran my life much of the time. I still felt small way too much. Maybe we all do during adolescence. The aching hovered around, waxing and waning, a weight at times, a memory at others. Jenny went from being a glorious distraction to a dull ache in about a week, and the ache for her got worse and worse. I ached for the people in my world too, those with limited intelligence or excessive sensitivity, and those like Geoffrey who had already suffered so much at the hands of others. I just ached.

Mostly I ached for the human race. Honestly. I had tried so hard as a hippy at rock festivals to love everybody, or at least not get really angry with anybody. But I had seen long before the meanness of a dark-skinned boy with an opportunity to settle accounts with a smaller lighter-skinned boy, and bullies picking on a fellow train spotter for no other reason than a desire to inflict pain and scare. A big part of my becoming a hippie at 16 or 17 was an effort, doomed to failure from the start, to deny such meanness in myself as well as in the rest of the world. The anarchists who disrupted the Isle of Wight concert and drove Joni Mitchell in tears from the stage reminded me of these earlier dark incidents and remained my starkest memory of what I had so wanted to be a beautiful dream. We were all so hopelessly flawed and weak. How were we ever to evolve and become truly beautiful?

The self-control which I sought to bring to bear to master my own human weakness had its own perverse effects. I saw them while hitchhiking, asking for something for nothing, day after day, month after month. Charity may or may not be forthcoming, and is entirely within the discretion of the driver. The hitch-hiker can make no reproaches. He can only offer thanks. I tried not to get angry, even when a driver would stop after I’d been standing for hours in the cold and then drive off after I ran up to the car. I was able to keep the anger under control for much of the time, but it made me numb. That numbness was the perverse effect of mastering my own human weakness. How can anyone whose feelings are blocked help us become truly civilized?

I thought ahead only vaguely, focusing on the short term. I was ready to attend Imperial College in London. After graduating, I would likely become a sales engineer, as dad envisaged, an engineer working with people because he had the gift of the gab. This was a future that didn’t excite me, but didn’t worry me either. Maybe I’d find a way to work on trains someday. The anomie I had glimpsed on the Canadian prairies had yet to kick in with any force. It was all very distant, almost dissociated, but I was still on track educationally, more or less.

Somewhere in there, I knew that I would go back on the road, in Canada or the US. I knew that I would visit Jenny. I would travel again that new world that still tempted from my bedroom wall. I was sure that I would make it all the way to California one day. From the American family in the White Swan who gave their bumbling young waiter such a handsome tip to the gentle young woman who was so kind to the inept, sex-starved suitor on her cold porch in upstate New York, America was in my life. It wasn’t Hollywood or the Kennedys; it was personal.

I sincerely wanted to avoid adult hypocrisy and lies, and swore to myself that I would be honest in my intimate relationships. If I ever had any, that is! I badly wanted physical intimacy, but had a very hard time seeing the link between that intimacy and a loving relationship. I was blunt and tactless and rude and called that sincerity and directness. I spent a lot of time on my intellectual high horse developing argument after argument in favor of myself, just as I had spent a lot of time in Birmingham developing arguments against mum. I did not bathe enough or wash my hair enough or change my clothes enough. If that turned people away, I complained to myself that they should see through these shallow indications to the real me. I was constantly bristling from real or imagined slights, and putting those whom I thought responsible down and finding fault with them. I tried to rationalize it by seeing it simply as a way to defend myself. But I was pretty mean too.

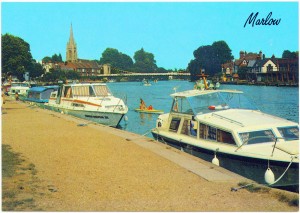

A picture postcard view of my picture postcard little town. The boats are moored on the towpath in Higginson Park, with the bridge and the town center behind. In SWOP, © Wycombe library.

There’s not a lot to say about coming of age in a modest life. Great things are not right around the corner. No powerful morals can be drawn from stories like mine, from the accidents and circumstances that somehow became me. What remains is eighteen years that were one long spring tide making its way in. Wave upon wave climbed higher on the beach and on the rocks than all the waves before.

There was the wave of bicycling four or five miles under the electric pylons to visit dad’s office in Filton, and the wave of watching a King class steam locomotive pound its awesome way into Snow Hill station. There was the wave of playing football with the big boys wearing winklepickers in Shirley and earning their respect, and the wave of scoring one glorious goal in the game between the Fifth Form classes at Borlase’s. The feelings ebbed and flowed as I watched the tide roll in. There was the wave of winning a scholarship to Solihull School, and the wave of exploring London’s main line stations on the tube with a little note in my pocket to be given to someone in uniform if I needed help. There was the extraordinary wave of the Beatles up on stage at the Hammersmith Odeon fooling around in their shiny grey suits as all of England screamed, and that was my beginning in the colored world.

There was the beautiful wave of lying next to Sandra after she took me walking down by the gravel pits in Marlow, and the exquisite wave of rolling around with her in Higginson Park another adolescent evening. There was the wave of the cod fillets that didn’t want to bicycle home in the snow one Christmas Eve, and the wave of the little Mini that arrived green and gleaming in our garage just in time for my seventeenth birthday. It was about seeing and feeling more and more.

There was the wild wave of doing wheelies on the main runway late one evening at Heathrow Airport, and the proud wave of being served chilled water by the Maitre d’ of the Grosvenor House Hotel when we looked like something a crazed cat had dragged in. There was the wave of the first time I saw the Rocky Mountains, like a dark grey and pointed cloud above the mist at dusk, and the wave of the first time I saw Jenny’s face labile and shining above the closed faces of the anonymous shoppers in Fredericton. There was the long, long wave of all those miles with my thumb out in the cold and the snow as the Canadian winter fell.

There were riptides too, failings, errors, some in the family, some in me. The vicious circles that developed out of the bad times, the wariness and the bristling, would remain to haunt me moving on. But they never really turned the tide. The dirt, the drizzle and the pallid greyness of the England of my childhood were just rocks for the waves to splash over. Boarding, single sex schooling and delayed physical development would have more substantial effects, but not yet.

A whole lot of love still flowed through our little family as it had as we moved around England and Wales from suburb to suburb, school to school and job to job, scrambling our way into a comfortable middle class life after that terrible war. I loved mum and dad so much, and Sue. They were great parents, we were a great family, and I was growing up very lucky. The waves just kept breaking and rolling in, year after year after year. They filled my heart then as they do now, remembering, drifting back. Maybe someday I’ll tell you more. We’ll see.

© Ian J. Stock

Previous chapter: Chapter 24 “Head out on the Highway”