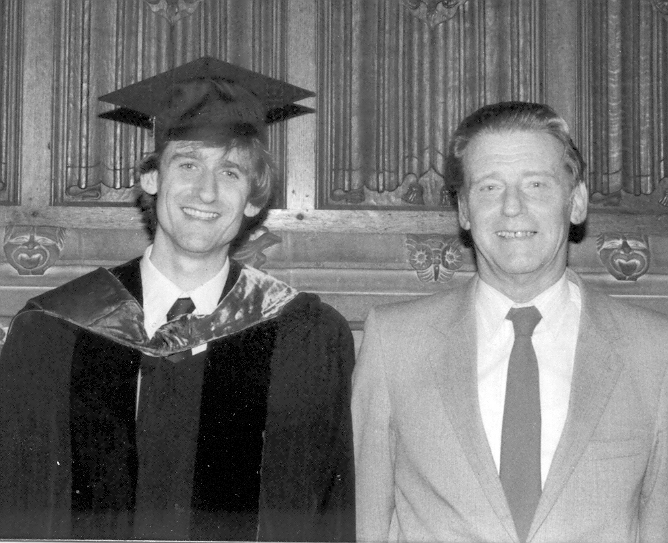

It was the morning of October 26, 1983. I was two months into my first real lawyer job with a real law firm, Kronish Kieb Shainswit Weiner & Hellman, in midtown Manhattan. Dad had visited during his September business trip to New York, and was very pleased.

The phone rang while I was in the shower. That was unusual. Neither Sunshine nor I was often called at home, more likely at the office, and early morning calls just didn’t happen at all.

Sunshine knocked on the bathroom door and walked in, handing me the phone and mouthing “it’s your mother.” If I had been given the time to be surprised, I would have been. I wasn’t.

“Jim’s dead,” mum blurted out, catching me off guard by calling dad by his first name, which she never did with Sue and me, clearly moved but a little abstract. She didn’t believe it either.

“I’ll get on the first plane,” I replied, feeling as if I was in a movie, and not a good one. I sort of was. Dad had lived through his first heart attack, quite serious, very worrying, when he was 46, twelve years previously, but he had survived that one and at least one other years later, and somehow I had stopped considering that he would die one day. He was my dad, after all.

The flight home was a sad collection of memories and grief. I hid in a corner on a row of seats with no other passenger, curled up and hunched over, staring out of a black porthole, and wept and thought and wept and thought. He had been a wonderful dad for as long as I can remember, a fundamentally decent man, about as honest with me as a parent could be. We’d had some pretty deep differences, some of which would live on, but the world felt as empty right then as that plane to Heathrow.

The highlights and lowlights kept coming: no sleep on a mourning roller coaster ride of memories. He really had done some extraordinary things for Sue and me. He had loaned her the money to put a downpayment on her and Derek’s flat and furnish it. He had given mum a car, one that she never once drove herself, on my seventeenth birthday!

And on top of them all, who could ever equal our 1964 Christmas present of tickets to see the Beatles at the Hammersmith Odeon? Both Beatlemaniacs, my sister and I struggled to hear the music through the screaming girls, and pretty much failed. But we could see them, and were close enough to see their shared glances and Lennon’s silly facial expressions. Seventh row seats! What luck we had to live that!

I sobbed during the concert, so much emotion swirling all around us, real passion for the hundreds of young women screaming uncontrollably, and I sobbed on the plane, for the good times.

Then there were his morals, always gently instilled, no fervor, religious or otherwise, which I had recently discovered. I had known the stories that he told for a long time, but their significance was only becoming clear after years of traveling and a fabulous education.

He had told of a very able classmate at LSE who, after not having been able to find a job in personnel work, his chosen field, because of continuing antisemitism, found work with Marks & Spencer, where he founded and developed their remarkable food departments and became one of their Managing Directors, or co-CEOs.

Antisemitism was not a problem in my (Jewish) law firm in Manhattan, but dad’s delicate moral education had taught me its unfairness and stupidity, and thus prepared me for its resurgence over the years.

There were reproaches too, even then, not 18 hours after I got the news, when I knew that I shouldn’t reproach: you don’t speak ill of the dead. But they were vaguer, more ambivalent.

Why did he oblige me to pay my own way through four years of college in the US and three years of law school? True, that would have cost a whole lot, but why didn’t he fly me back from California during my freshman year of college to Sue and Derek’s wedding? That was a reasonable cost, and he often did pay for my flights home and for his and mum’s to visit me in California.

The ambivalence came from my knowing the answers. He didn’t want me to leave the family and England, where I had dropped out of Imperial College and abandoned a full industrial scholarship. He didn’t understand why I went to UC Berkeley, not quite the school that he would have chosen, and he wanted to teach me that living abroad made it more difficult to keep in touch with family.

Lessons learned, I thought ruefully, as I made my way back thousands of miles to join mum and Sue.

I had already learned talking with mum again over the phone – she had still sounded abstract, detached – that dad had been taken ill in his hotel in London.

He was typically away on business one or two nights a week. Staying overnight in London, only 30 miles from home in Marlow, was a relatively new twist, but made sense. Just as when he was visiting the north of England or somewhere in Europe on business, the dinner would finish late, so in London too.

Arriving in Marlow, it was all a whirl, not a lot of sleep and it was the next morning in England. I don’t remember how I got from Heathrow to home or how I found out the key fact:

dad had not been alone in that hotel room.

Sue must have told me. After falling ill, he had been rushed to St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington – another St Mary’s, 5,000 miles from the first – where Alexander Fleming had discovered penicillin, where modern royalty was born, and where he was declared dead. Sue and Derek were living in Solihull, and had driven straight down to the hospital, talked things over with dad’s girlfriend and brought his personal affairs home.

The other woman was not entirely a surprise. I had been pushing dad for years to spill the beans, and he did one night over dinner while I was visiting from law school, I think in 1981.

He was very uncomfortable doing so, because he knew how protective I felt of mum, but he sensed my need to know the truth, and owned up to it. I was very grateful to him for doing so, but knew that mum would be terribly hurt if she ever found out.

Then during a visit with him in New York in early 1983, he met two very attractive women, maybe late 40s, in the bar at the Pierre, where we were staying, before I came down from my room to meet him, and invited them both out to dinner with us at the Russian Tea Room.

The conversation flowed easily over dinner. Dad was his usual charming self, which was very charming, and the women, both of whom were childless, enjoyed our father son repartee on the topic of my finally getting a real job. “It’ll soon be your turn to take care of me!”

It turned out that each of dad’s guests had married a very old, very rich man with no family, and each man had the decency to die not long after the marriage, I bet much happier for his recent good fortune. After dinner, dad had the taxi drop me off and then took them to their respective homes, I think on the Upper East Side. I didn’t bother to ask him for details. He was very happy that evening.

At that earlier 1981 dinner, after his first admission, dad had pulled out his wallet and showed me photos of a few “friends” which he kept there, one of whom was perhaps 30 years younger than him. It was a great relief back at home in Marlow when I was able to locate his wallet, soon after arriving, and extract the photos that were still there. Hopefully, that was enough to protect mum from what had happened in that London hotel room. Dad had been very careful to keep his adventures secret, and I was sure that mum would be deeply hurt if she found out what had happened.

Mum and dad had a great relationship on many levels, but not on all. They shared their worries about us children, talked a lot about a lot, current events, holiday plans and neighbours and friends, they watched TV and did crosswords together on the couch, dad doing the Telegraph and mum the Express, but family dynamics had already caused rifts and areas to be avoided: don’t they always?

And Mum was chronically ill – Cushing’s Syndrome seemed to be the centerpiece – and had already expressed her appreciation for dad no longer bothering her on an intimate level. But that never meant that she was okay with dad going elsewhere.

A day or two after I got home, as she was examining what was left of her husband of 34 years, mum was going through the contents of his briefcase sitting in her habitual place on the sofa, next to the coffee table, when she found an insurance company envelope with a hand-written letter inside.

She called Sue, Derek and me into the room and asked us to sit down. We’re looking at each other, I’m thinking, “shoot, why didn’t I check the briefcase too?” and mum started reading. She had a wonderful speaking voice, and read the contents of the letter clearly and well. I was looking at the wallpaper and curtains, examining the fireplace opposite my armchair, doing anything but looking at the other people in the room, as she carefully continued her public speaking exercise. I’m thinking, “shoot, why didn’t Sue check the briefcase? She brought it back to Marlow.”

Despite the betrayal evident in the words that she was reading, mum continued to enunciate evenly, almost without conveying the underlying feeling. Yet the letter itself was already full of emotional drama.

The writer covered their “first evening” together – “ah! It’s a new relationship, I thought, “maybe that’ll help” – but it didn’t.

“Whatever else happens, I shall remember it as a totally perfect occasion, no reservations at all.”

The letter was well-written, carefully thought through. “I can tell you that on my 25th birthday I made a resolution, which I had not broken, not to commit these matters in writing ever again. You can work out how long ago that was.” So she was no longer young.

There were two postscripts, which mum dutifully read out in the same neutral clear tone. The first referred to the stationery. “You can see that I followed the precedent laid down for paper and envelopes.” Unidentifiable paper, I thought, and a misleading envelope: the best laid plans of mice and men . . . . After years of careful secrets, scrupulously maintained even when they became ridiculous – he lost his AmEx card over a dispute with the issuer about a dinner which said that it was for two when dad insisted that it was for one – Dad blew his big secret. And it wasn’t even his fault: he couldn’t have known that he was going to have a heart attack and die. But the letter that he left behind revealed how carefully he had planned at least this excursion. A spontaneous and limited event this was not.

Sue and I carried on with the logistics, arranging for the funeral, starting the process of summarizing his assets and going over his will. Sue was his co-executor – another of his reminders about the consequences of my living abroad – but my memory is that we worked on things more or less together. And her co-executor was Douglkas Deakin Young, a financial management firm appointed by dad in his will, which helped keep things in order.

Reed International, where dad had worked as a Personnel Director, or VP of HR, had a great fixed benefit plan for executives who died on the job (perhaps not the right phrase to use here!), which gave mum a widow’s pension of 4/7ths of dad’s final salary for her lifetime, paid off the balance of the mortgage on her home, and paid her in total four times his annual salary as a lump sum. She was well taken care of. As dad was the corporate officer with primary responsibility for the pensions of his own management team, he had again taken good care of her.

My most moving moment was looking through his bank accounts. I knew that despite rising to a high level in a public English multinational, UK salaries were way behind US salaries and he had never earned enough to cover his family and make significant savings or investments in stocks or whatever. But the accounts revealed weekly deposits in savings accounts, joint with mum, and other signs that he was trying to prepare what he had in order to support her after he died. I remember thinking to myself that he had done so much, and then dissolving into tears when I realized that he might have been doing so because he sensed that his heart was not going to make it. Such a big heart: so unfair that it did not reach the retirement he was already dreaming of and planning. He fancied buying a pub somewhere.

The day before the funeral, I had a strong urge to visit the funeral parlour and see him one last time. This was allowed before cremation – not a religious man, he had willed that he be cremated – and I was admitted at around dusk, and left to myself with dad and the flowers which had already arrived.

Seeing his face, which had obviously been prepped for just such a visit, was a shock. The life force had gone completely. I tried to explain it by examining his features to see what had changed: his mouth was slack and wide, for one thing. But it wasn’t any change in the features. He was visibly, unmistakably dead, that’s all.

I talked to him for a while, telling him how happy I was that after ignoring my Berkeley graduation he had attended the one at Yale Law, and thanking him for the year after when he mostly supported me as I thought things through. That had been a great year, living beyond my means in a windowless studio in San Francisco’s Mission District, and partying all across the city!

I was grateful for his appreciation of my starting the kind of career that he had always wished for me, as a corporate lawyer. He didn’t visit my office that trip, but he did stop by our first New York apartment, a corner one-bedroom, still pretty much unfurnished but with great views, on the 21st and top floor of a doorman building on the north side of the Village. I choked up as I saw him again as he waved goodbye at the front door on his way out. My last glimpse of my dad.

In a bit of a state by the end of this discourse, I started examining the cards on the numerous bouquets arrayed around him. This time, thankfully, I saw the problem even though I wasn’t looking for anything. Some of the bouquets, four or five, had a solitary feminine name on the card, and wondering about that through my tears, I realized that these might be women that dad had been involved with. I arranged with the funeral parlor to put these bouquets in dad’s closed coffin.

My apologies to any one of those women who was not involved with dad, but I had to try to save mum from the worst.

Not sure that it worked, because I did notice a few women at Amersham Crematorium the next day who could well have been looking, unhappily, for their bouquets. But it was a busy time, and mum might not have noticed. There were a lot of people paying their respects, family, friends, colleagues, and many wanted to give mum in particular their condolences.

That was it: the death had been ritually competed. We all went on with our respective daily lives.

There were more consequences, of course, over time. Mum professed her personal certainty that the woman in the London hotel was a one-off, and that dad was basically faithful to her. I don’t think that she believed it. She was too smart for that.

When the Crematorium wrote to her in 1993 to ask if she wanted to renew his little plaque planted in the garden there (apparently the initial fee only covered ten years), she ignored it. Wanting a continuing memorial to my dad, I arranged for his name to be added to mum’s grave in Birmingham after she died. This confused people, who thought that dad was there too, although the other occupants of the grave were mum’s siblings and parents. I regret causing confusion in such a place.

I thought for a long time about going to see the woman whom Sue had told me had been with dad when he died, but decided against it. She had been through enough already. “Pull yourself together woman,” she wrote in that famous letter, “you can manage Mr. J. E. Stock.” And after a pause, the second postscript read: “Will this join the category ‘Famous Last Words,’ I ask myself.” It did, but hardly in the way that she would have hoped.

Mum lived another 13 years of declining health, financially comfortable, often evoking dad but rarely his possible excursions, at least with me. I think that a part of her died on the day that she read that letter out loud, but that may be me assuming that she felt it as strongly about it as I did.

Forty years later, I have come to terms with my dad. The manner of his death had disrupted my unbounded enthusiasm for his character and moral education, but over time it became a part of him, and not the main part. He had been admirably careful in his excursions, always, even if dying “on the job” – I joked at times that he had not known whether he was coming or going! – caused that careful structure to crumble. His concern for the workers in his companies, for the mistreated and dispossessed, never faltered.

He was a beautiful man. It’s that simple. He had a weakness – don’t we all? – but the beauty won, at least for me and Sue, if not for mum.