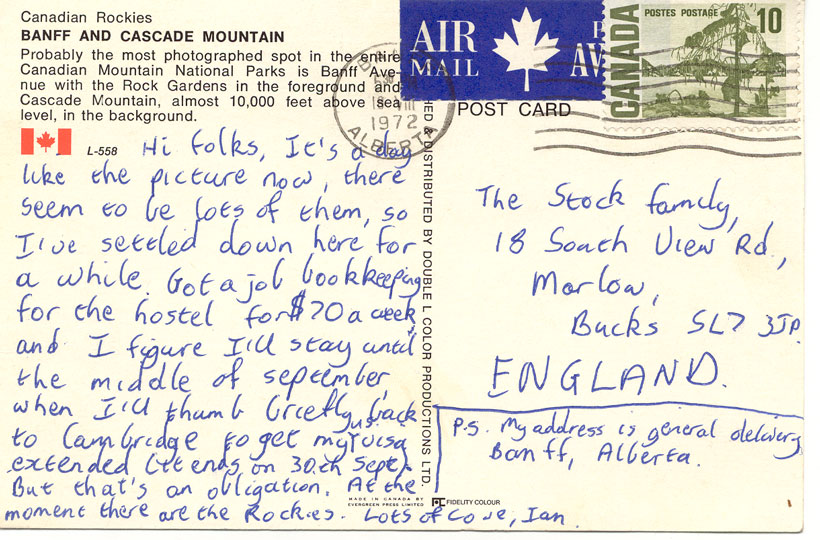

As soon as I found the hostel job in Banff, I sent a postcard home to give mum, dad and Sue my address: General Delivery, Banff, Alberta. The picture on the card is in the middle of this post. On holiday at nineteen, keeping in constant touch with my parents was not at the top of the agenda, but my keeping within reach did seem to be important to them. So whenever I was going to be in one place for long enough to make it worthwhile, I’d let them know.

I also periodically called them. Not too often during this summer, because the phone company had linked the telephone credit cards I occasionally made use of (whose numbers were published in an Abbie Hoffman vein – “Steal This Book” – either in the Village Voice or Rolling Stone: I forget which) to the Roys in Cambridge. They had been my initial hosts in the US, on the high school exchange trip which became my first step to emigrating. No longer having access to to those credit cards, and having been discouraged from making collect calls home (dad was always very focused on money!), I was not making a lot of calls to the family.

I made one from Banff on Thursday August 24, according to mum’s diary at the time, which I found in her papers after she died in 1996. I was just checking in before leaving the hostel when it closed at the end of its summer. Mum was delighted that I had called, and informed me that, with no apparent warning, dad had had a serious heart attack the preceding Saturday. He was 46. I was shocked: mum was our sick parent, with sometimes bizarre ailments, not dad.

Mum immediately went out of her way to reassure me that he was over the worst of it, and no longer in any danger. In her first letter, she wrote that the tests administered after the attack confirmed “that the heart is as sound as any other heart in a man of 46, so much so it’s puzzled everyone including the Specialist . . “. In retrospect, I see that medical conclusion as pointing to the inadequacy of such tests in 1972: then, the specialist’s opinion was very comforting.

Mum wrote to me quickly, on the day that I called, to fill in the gaps in what had happened. They (mum and dad) were rushing around quite a bit that summer, and dad spent the week before he fell ill helping the decorators, moving furniture, cleaning up after them. Not quite sure how that happened: gardening was his hobby on summer evenings, and helping the decorators allowed him no time to garden. He was working as normal all day in central London, an average of twelve hours a day including a difficult commute, and then doing the decorating at night.

Dad did not like to feel sick, and denied it as much as he could. His own father had a weak heart, which had kept him off his feet in a care home for most of dad’s teenage years. No way that dad was going to repeat his own father’s pattern!

That Saturday, mum wrote that he started feeling indigestion after a late lunch, and began complaining about it to her at tea time as it worsened. After a walk to try to settle his stomach, he went to bed around 10 pm, feeling very bad, and refused a doctor’s visit when mum suggested it. Twice she suggested calling the doctor, and twice he refused.

“For the first time in our married life I ignored him and phoned the surgery,” wrote mum in her letter. In doing so, she likely saved his life. I was in Banff. Sue was out on a date with a boyfriend, and did not return home until about lunchtime the next day.

Dad was taken to hospital very soon after mum called Doctor Spink at the surgery, arriving around midnight, and stayed there for ten days of specialist treatment and often sedated rest. Nowadays, hospitals rate their performance with heart attack victims by the number of minutes it takes them to get the victim proper treatment. They say that this is because minutes count in preventing fatalities. My guess is that the urgency was similar back then.

Dad did not necessarily see what mum had done for him. His strongest feeling for a while was annoyance about falling so ill. As he wrote from his hospital bed, “I am having an enforced rest, much to most people’s delight, if not to mine.” I want to add an exclamation point there!

After hearing the news, I didn’t go straight home. I didn’t return to Marlow until months later. Writing that now, it does feel insensitive. But it didn’t feel that way then. I thought it over late that August, but not too much. Dad was in good hands, medically and at home, and by all accounts, was convalescing as well as could be expected. He, mum and Sue wrote regularly during and after his hospital stay. I did not see that I could contribute a lot.

I was aware that by staying in North America I may have been hurting his feelings, especially if he wasn’t himself, as mum had written more than once and as the sometimes quirky portions of his short letters seemed to indicate.

For his birthday on September 5 (he returned home from the hospital on the Saturday, September 2), I sent him a little verse I’d composed for him on the inside of his birthday card, another postcard, this one with a photo of Lake Louise. It read in part:

“I looked at all the greetings cards parading in the store, and some should have said a little less, and some a little more. . . .

By way of a birthday greeting, I don’t know what to say, save enjoy yourself and be careful, and have a trippy day.

And now don’t feel bad, you’re just the perfect dad, and remember we’re sharing today.”

We weren’t sharing the day, and I did realize that a glib rhyme couldn’t change that.

But it didn’t matter. I was 19 years old, and finally free. Lauri had already sent me $20, real money in those days, to bring her some rabbit’s feet from a trading post in Banff to her place in Aspen, Colorado. And that’s where I was going next!

In England, dad was released from hospital on schedule, and a few days later mum and he took the train down to Cornwall for a week’s rest. The doctors did not yet allow him to drive. According to her letter, mum was quite pleased with herself for making those arrangements.

Reading between the lines, the strain was beginning to tell, and during the next holiday, a previously booked week in Italy, something seemed to snap. Mum wrote in her diary that the week would be “best erased from mind and memory.” Then her diary went pretty much quiet for a few weeks. That tended to happen when she was very upset.

The diary started up again a month later, in October, when she initiated a plan to come and visit me on the East Coast. Whoa! She was coming to visit me to help herself get over the strain of looking after dad. As I pointed out to her, relatively gently, it was dad who had suffered through a heart attack, and yet it was mum who was coming to convalesce!

Her response was a conviction that dad was fine with her going, and understood and supported her. Yet in his first short letter to me from his hospital bed, only a month or two earlier, he had written, “I wish very much I could be, or we could be, in Banff too – it looks rather smashing.” His initial impulse had been to visit me himself in North America.

I felt trouble brewing, but could not refuse mum’s visit if dad was okay with it.

Accustomed as mum was to dad looking after her during her own various serious ailments, from the polio of the early days of her marriage through the constant repercussions of a slipped disk and on to surgery to untangle her three kidneys, she had been completely taken aback by the role reversal that followed dad’s heart attack.

She needed a break, a period of being looked after herself, and that’s where I came in. Dad wanted mostly to keep the peace, and once mum raised her desire to visit me, my guess is that he will have accepted it, even encouraged it, to make her happy. That’s how he always was, trying to keep everyone happy.

Not an easy task, as the complaints in mum’s diary showed, and as his own letters revealed between the lines during this period. He was clipped, even edgy at times, not like him at all.

But there was nothing said or written directly, certainly not to me, and I would guess not to mum. He and Sue did write to me during the period while mum was visiting the US and Canada, and it was very difficult indeed to discern any resentment about mum’s “convalescing” on the part of either of them in those letters.

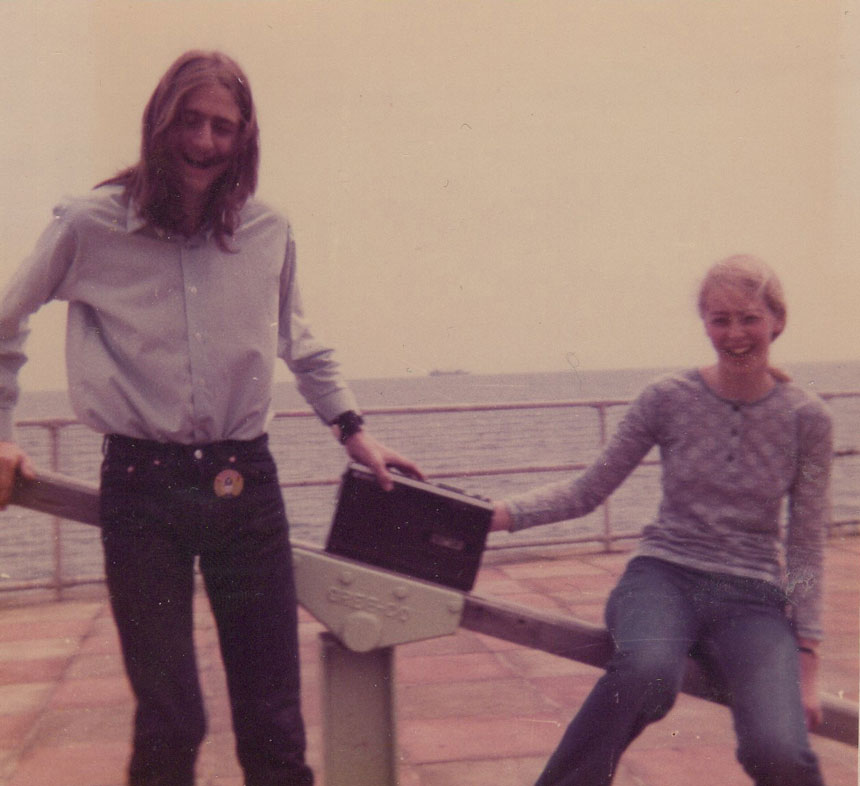

A little surprisingly in the circumstances, we had a great visit, mum and I. I thumbed back from Colorado to Cambridge, east of Saratoga, New York, where we were based with the Roys for most of the visit. Mum was concerned that I might be bored there (no way!), and so we were going to make a little tourist visit to Toronto, one of dad’s regular ports of call on business.

Dad had made it clear that mum and I were not to thumb (as if I would hitchhike with my mum!), and mum rented a new car, a Mercury Marquis, at Bennington Ford across the Vermont state line, for the middle week of the trip. We drove up to Ontario together, by way of a friend’s place near Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. I was showing her something about what it was like for me to travel in North America.

The roads were frozen for hundreds of miles, and the car slipped and slid most of our way to Canada and back. I had already learned how to drive in snow and ice on the Trans-Canada Highway. Mum implored me not to pick up a derelict guy thumbing near downtown Toronto, and so I left him on the side of the road. Imagining some convoluted and criminal scheme, US Customs emptied her bags searching for contraband, and didn’t so much as glance at mine!

Mum returned home at the end of November, as did I a few weeks later, and life progressed pretty much as you might expect. Dad recovered well and went back to work on schedule, first part-time and then full. Sue continued with her schooling, taking her “A” levels at the end of the school year in July 1973. I continued traveling.

The heart attack and its aftermath did have real effects on us as a family. The generational conflict which had such a profound impact on so many families raising children had not happened in mine. I always wanted to return to the American West, true, but that meant nothing against mum and dad. I still felt very close to them, and felt sorry for the young people with parents less in tune with the new order of their children. I had already forgiven them for sending me to boarding school five years previously.

I remained proud of how well my parents got along with my friends, even those like Adrian who gave them pause. I was relieved that they still let me go, as they had done when I was still a child and rode on trains by myself to trainspot, even though there was obviously much more in play now from their perspective. Enough was going on inside me that I was grateful for the absence of the kind of harsh parental conflict that so many people I met on the road reported.

But unstated or understated conflicts did increase. Mum had written to me in Banff that Sue had taken dad’s illness particularly badly. She was only 17, and dad was her “rock of Gibraltar,” as mum put it. 1972 had already been quite a year for Sue. Her dating habits were evolving rapidly, as she explained in a couple of her letters during the year. The letter which mum brought with her to the US blew me away. She was “going out with those three blokes,” previously described in the letter, including a new one named Derek, “who makes me laugh.” Following her September “depression,” she was “undergoing a considerable realisation of my self-confidence.” Great news!

Then there were her relationships with mum and dad.

Before dad’s heart attack, mum had written that she and Sue were getting more distant, which was “alright” because dad and Sue were getting closer. Then Sue wrote that she had broken the house rules when mum and dad were away for dad to convalesce, because it “was so nice to get away from having to watch what I was saying and where I was going and when.” That came out because mum read a letter that Sue had written and deferred sending to a friend of hers. And mum was the disciplinarian, not dad, whose modus operandi was to influence, with subtlety, rather than discipline.

The heart attack set in stone the period of mother daughter difficulty that often characterises late adolescence. Not only was mum enforcing order, she then went away and left Sue alone to look after her rock of Gibraltar. Sue never forgave mum, and that spread to me too.

So it was that at my niece Laura’s wedding in 2009, over 35 years later, Derek, the bloke mentioned for the first time in Sue’s November 1972 letter, who had married Sue a couple of years later, cited my not returning home after dad’s heart attack as possibly a key reason for Sue’s and my having drifted apart over the years. I must suppose that as her husband, Derek has a pretty accurate sense of what Sue feels. It wasn’t what she felt at the time, but it became the future.

Dad and I splintered apart too. He never talked about it, literally never, but he did try again to bring me back and settle me down near home. If I didn’t want to go to University, he would look elsewhere. In early 1973, I worked for maybe two months 12 hours a night five nights a week for BRS Parcels, a nationwide parcels delivery company, at their warehouse in the Cressex estate in Wycombe.

The work involved moving boxes off the few big trucks which arrived early in the evening, hand-trucking them around the warehouse and depositing them in the allotted spaces for the numerous delivery vans that were to deliver them the next day. Doing this 12 hours a night was mind-numbing. The overtime suited me, because it was the best way to make a warehouseman’s pay suffice to save quickly, but the trip home at 5.30 am, before the first bus, was a real drag in the early cold and mist. I would hitch as I walked the three miles home, but sometimes greeted the dawn and walked all the way.

The warehouse manager apparently liked me, and suggested that I sign up as a management trainee for the company. Dad jumped on this idea, and eagerly supported it. “Thanks, dad, but I don’t think so.” How would being a BRS Parcels management trainee be any better suited to me than being an electrical engineering student at Imperial College?

It would take me many years to realize it, long after he died, but he would never really forgive me for not coming home from Banff. We never discussed it, and he never reproached me. I only perceived it indirectly. The advantage of his indirect approach to family issues was that explicit conflict almost never happened. The disadvantage was that each issue was rarely clear, and the air around it was often never cleared. We never did reverse the damage done by the combination of a weak heart and a nineteen year-old boy on holiday in a paradise of girls. I never meant him any harm. I hope that he knew it.