Mum in front of Grandma’s house in Kendrick Road, Slough, with Tiddles in 1951. That wary black cat, called the “old lady,” lived until late 1966, following us to Cardiff, Bristol, Birmingham and finally Marlow.

Of course I never knew my own birth and infancy. Infancy is the time in your life when your own ignorance is the most obvious, and when we all realize that we are necessarily interpreting events relayed by others rather than describing what we lived ourselves. The distorting effects of our own memory have no place.

The converse of the absence of memory is that almost all that you know about birth and infancy comes from those around you. The story of my birth came from mum and dad originally. I loved to hear it, and would prompt mum and dad to recount it again, pushing each of them for more details. It was shared among us all so many times that as my sister Sue and I grew older each of us could bring up details that we already knew. On the other hand, perhaps Sue was less interested than me!

The fog was the star, a great British pea-souper that covered southern Buckinghamshire and the rest of Greater London for the whole weekend and then some. It obliged my father to walk in front of the ambulance to show the driver the way. Think about that for a moment. The ambulance had headlights, and the road was a perfectly normal road, but the driver could not even see it a few feet in front of him!

This is not what we call fog fifty years later in California, when it rolls in off the ocean on Monterey Bay and slows us down to maybe 40mph on the highway. This was opaque, solid, a complete and impervious gaseous block. It must have been a long walk, too, because the maternity home in Burnham was several miles from the modest little semi-detached home that mum and dad shared with Grandma Stock in Slough. Mum was in labor the whole way.

Mum and dad taken on a day trip to Bournemouth in 1951. Mum wrote on the back, “Day I Caught Polio.” Before I was born, she was given the Catholic last rites, the last sacrament, when the doctors feared that she would die from polio. Dad’s future health problems can be seen in his left hand.

47 years later, a documentary on the History Channel in the US listed that very same pea-souper in December 1952 as one of the ten most significant environmental disasters of the 20th century in the entire world. Tens of thousands of luckless souls are estimated to have passed away over the ensuing months as a direct result of the stagnant concoction of industrialized English chemicals that hung and swirled, thick, yellow and choking, over Greater London for days on end.

The History Channel had extensive coverage of reports of the yellow color of the fog and of the inversion effect in the Greater London basin. London and Paris have the same inversion effects and basins as Los Angeles, although with their European climates each is less conspicuous than LA., except of course when there is smog. Mum and dad never mentioned the yellow color in their recounting the story, or the enormous fatality rate attributed to that fog. Perhaps they didn’t know about all the fatalities.

That is not how the fog and that story made their way into my life in later years. Rather, it served as a pleasant anecdote for the Americans I met to confirm their stereotypes of England. “Is there fog in London? Are you kidding? Why, the day I was born my dad was asked by the ambulance driver to walk ahead to show him the way to the clinic. The driver lliterally could not see through the fog to the road in front of him! Now, that is fog, let me tell you!”

Mum’s problems did not stop when the ambulance finally brought her to the maternity clinic – after how many hours waiting for the ambulance, and plodding carefully along the road through the evening? They discovered that the Ian baby did not want to come out. After some exploration, without modern non-intrusive techniques, of course, they discovered that I was in the elongated breech position, butt first and head between by feet. Ouch! This was a far from natural position that made it extremely difficult for mum to give birth.

In 1952, childbirth was a much riskier and more painful process than it is now, without those amazing ultrasound images of the fetus. Mothers regularly went through the hell that mum went through, and worse. Mum’s hell lasted something like eighteen hours. The midwives were forced to use laundry-style tongs to break the deadlock. I was so black and blue that they would not let mum see me for a week. Dad insisted on seeing me, but never did say too much about it.

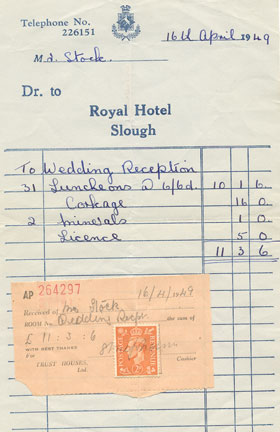

The receipt for mum and dad’s wedding reception.

I occasionally view this sequence of events in an odd way that I am embarrassed to repeat. Especially as she became more and more a creature of her various illnesses later in life, mum could be very controlling and pushy, to the point of driving the object of these demanding attentions to somewhere approaching crazy. My sister Sue and I tended to be the objects of mum’s demands, and Sue was duly driven more or less crazy from time to time. How crazy I was driven is demonstrated by the habit that I developed of reassuring myself that mum could not go too far with me. “She had already tried that when I was born,” I would think to myself, “and it had almost killed her. So now she would show more respect and restraint.” As I say, a little embarrassing.

Mum, Bob and a bear in Cortina d’Ampezzo in 1947. Sometimes orphans do okay: the timing of mum’s military service, almost entirely after the war was over, was as impeccable as were her postings, uniformly to beautiful holiday resorts!

Oddly enough, completing the embarrassing side, the elongated breech and mum’s and my pulling through it gave me an irrational but convincing sense of having overcome great odds from day one.

Not much remains from Slough: receipts from mum and dad’s wedding reception on April 16, 1949 in a drawer at home, photographs of the wedding, black and white, of course, and of mum and dad’s occasional vacations together, and that’s pretty much it. Not much remains except, of course, for the stories.

Another was how mum and dad came to meet. Each was demobilized by their respective armed forces, abbreviated as “demobbed” by all and sundry, at about the same time. Each ended up in Slough. Mum had lost both her parents to cancer, her mother first when she was 10, and her father when she was 17. An orphan of the industrial revolution, which killed with cancer above all else, she had nowhere to go but to see one of her sisters after being demobbed. She picked Vi because Margaret was waiting for Ron to come home from the war, or perhaps he was already home, and they had six years of separation to catch up on.

Aunty Vi was mum’s next older sister (Margaret was the oldest), christened Violet Rose Eliza, a wonderful turn-of-the century English name. She had been recruited to take care of Grandma Stock for a while, and lived with her. Grandma had been widowed in 1944, not by enemy action but by Granddad’s weak heart. He died at the age of 45. Because she herself was chronically ill, she needed help taking care of herself.

Our family’s honest-to-God hero, Uncle Ron, on his wedding day in 1939. He then left for six unbroken years in North Africa and Europe as serial # 10537295, Sgt. R. Whitton, R.E.M.E. The cute little minx next to him biting her lip is mum, then 12 years old! Aunties Margaret and Vi are on the right.

Dad came back to his mum’s house, and started commuting weekly into London to go to LSE (staying with a cousin in town) soon after he started dating mum. He was studying personnel management with a little help from the army, and because he had no money other than the pittance that the government paid ex-soldiers, he lived with his mum. Mum was earning a Certificate attesting to her proficiency in operating the comptometer. A comptometer was a cut above an adding machine waiting for the computer to arrive.

Mum and dad were not heroes, although both had joined the army. Dad had been assigned to an Intelligence unit, and thanked the Army for the rest of his life for identifying his interest in training and people. He had left Slough Grammar School expecting to become an engineer. He was also taught Japanese by the army in Scotland, less usefully for his future, and at age 19 was just about to be sent to help the Americans in the Japanese war theater when they cancelled the trip by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

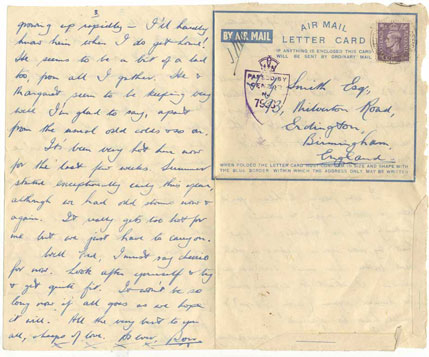

Uncle Ron wrote to his father-in-law, who was ailing, in 1944. He writes about his son Peter, “growing up rapidly. I’ll hardly know him when I do get home!” He writes about Aston Villa winning the FA Cup, England’s premier soccer tournament, because Fred painted the stands at Villa Park and was of course a Villa fan. Uncle Ron was chatty and warm and friendly, hopefully back in England soon. He did not return in fact until long after his father-in-law had died and Peter had turned six or seven years old.

Mum signed on with the ATS, the women’s branch of the Army, at seventeen and a half, the youngest possible age, because she felt that she had nowhere else to turn after her father died. She spent about three years in the service, and somehow managed to be posted to Venice Lido and Cortina d’Ampezzo, two of Europe’s top holiday spots, where she did not suffer greatly from the privations of military life. The GIs that she met there had looked after her. She was very fond of them. She did divulge obliquely in later years that she had found one of them a little pushy, a little demanding on an intimate level, but her enjoyment of their company was clear. She was even engaged for a short period to a GI from Arkansas. I think that his name was Eddie.

Uncle Ron, Aunty Margaret’s husband with the penchant for Jaguar cars, was our family’s genuine hero. He had earned his Jags. Mum and dad’s military years were brief and almost pampered. Uncle Ron had spent six long years as a part of Field Marshal Montgomery’s army, first making its way all across the North African desert, and then all across Europe. He did not once return home on leave to see his wife and son the entire time. He would never talk about what he had lived, even when we would try to sneak it into the conversation, and he tried to be pleasant at all cost, his bright blue eyes constantly shining. He had such beautiful blue eyes. It was as if he willed them to sparkle and shine, to hide what he had seen and make the rest of us forget all about it just as he yearned to. I don’t think that he did forget, and suspect that he never quite got over the effects of those six years away, making war.

Not a lot of pictures of baby Ian to be found, unlike toddler Ian. This one was captioned, “Ian James at 7 months, with all our and his love, Cath & Jim.” Dad wrote it, apparently to Grandma. According to my mum’s notation on the back, it was taken at a park in Cardiff, and the timing, June 1953, was right around when we moved there. From the look on Dad’s face, he’d already run amok.

There were many heroes like Uncle Ron, in Montgomery’s army or elsewhere in the British military, and many stories of incredible valor. Some are well known, like the story of Guy Gibson’s extraordinary “Dambuster” squadron, with its bouncing bombs and heroics that appear almost absurdly courageous viewed after the war, but most surely went unreported. That was the volunteer military.

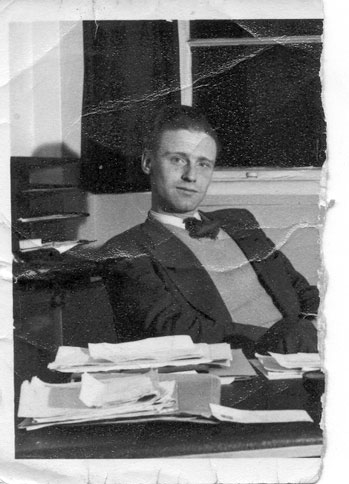

Dad played hockey with the Old Paludians, Slough Grammar School’s Old Boys team, until he left Slough and even occasionally thereafter. Here were a group of them, with dad on the ground at the rear, in Marlow in April 1952. We Stocks would return to settle for good in Marlow in 1966. Who is the young woman almost hiding at dad’s right? Where was mum, who was expecting me?

The majority of England’s people were not in the RAF and lived more or less terrified of German bombs, the random slaughter that threatened so many constantly from the skies for years. The 1940-41 Luftwaffe blitz of London, months of almost nightly bombing, extended from time to time to many of the English industrial cities. For their protection, schoolchildren were sent en masse into the country to avoid the bombs. Families already pulled apart by German hostility were further torn by the bombing.

It was balanced, in a perverse sort of way, that dad escaped active service in the theater of war abroad because our side had rained down hell from the skies on the other side when much of his entire country had spent years dreading a similar rain from hell.

When mum and dad married at a Catholic church in Slough, there was not a lot that they could do but live with Grandma, even after dad won his LSE diploma in Personnel Management and found his first job in Staines, only five miles each way on his bike. “Get a better job at Petter’s” said the company’s adverts. He did, but the after-effects of the war were still very present in day-to-day life. The country was breathing a collective sigh of relief: Hitler was dead, the bombing had stopped and a baby boom was starting. But seven years after the end of the war, as the US accelerated into the most prosperous period in its history, dad was earning peanuts and paying the excessive taxes needed to rebuild a broken country after a terrible war. Grandma gave up her fruit rations to mum when she was expecting me.

Children feel guilty all the time about things that are nothing to do with them. The turn of events that transformed our family so soon after it began had nothing to do with me, even if it may have had something to do with my birth. If psychologists are correct that the birth of a child panics the father into seeking reassurance elsewhere, then what happened was to do with my birth. If it was simply dad’s character, or an inevitable result of his relationship with mum, then I was not implicated.

Mum’s caption says it all: “I wonder where the other half is?!?!” She spent most of her married life wondering where the other half was in one way or another. Which is a great illustration of the fickleness of interpretation. Sure, the other half could have spent its life in another woman’s purse, a poignant reminder of a doomed affair. Or it could have been thrown into the garbage, because dad did not like the person in it. Then again, look at the sadness in dad’s expression in the photo. . .

What happened lurked in the background for a while before it came home to roost, maybe a few months, maybe longer. I’ll never know. Dad found a better job elsewhere, one of the themes of my childhood, in Cardiff. When exactly he and mum moved apart is not clear, but they decided that he should move away to South Wales, something more than two hours away by train, to take the new job. Mum and I were to rejoin him later. Before we could do so, he had embarked on, consummated and finished an affair. Mum and I moved to Cardiff when I was only six months old, and I don’t really understand when dad fitted in the affair, but he did. I never knew anything at all about this first mistress, and don’t think that mum knew much. I don’t even know whether she was in Cardiff or Slough.

To make matters much worse, dad protracted the affair and introduced it irreversibly into the marriage by announcing it to mum. It is a peculiar sort of egotism, expiating one’s guilt by inflicting terrible pain on an ignorant victim. But perhaps she was not so ignorant. Perhaps she was terribly aware of, or tortured by doubt about, another woman. Perhaps that torture was such that continuing with him without his admitting it to her would have been worse for her. Again, I’ll never know, but to be honest I doubt the latter. Mum was more than a little naïve about intimate matters throughout her life, and may well not have had the slightest idea that dad was having an affair. And even if she did, I’m sure that she would have preferred not to know.

They stayed together after that emotional explosion in Cardiff, in part I would guess because that is what married couples did then, in part because mum basically had no alternative, in a city that she knew nothing about with a newborn baby and no parent left to take her in and coddle her. Their life together, our lives together, must have been particularly unpleasant for a long time. Mum must have been hurting dreadfully, and she was not one to hold back her reproaches: far from it! By the time I was capable of reason, I saw her as both very vulnerable and, when hurt, very vituperative. Even dad, the perpetrator of the wrong, was very sensitive and prone to guilt, as was demonstrated by his confessing the stupid affair in the first place. Mum’s misery and reproaches must have been interminable. I doubt that life got back to normal for any of us very easily.

The affair and its aftermath became another part of our family’s collective story, a part of all our futures that remained a lot less pleasant for me than my birth. I was only about nine years old when I first heard about that affair, in our home just outside Birmingham, from mum of course. In a sea of barely remembered and unremembered incidents, this conversation is one that still feels perfectly clear. We were in the lounge at Skelcher Road in Shirley, and mum’s face was so earnest and her voice so careful as she told me what dad had done. I knew immediately that it was an important moment. I remember feeling distinctly uneasy, sympathetic because it was all so important to mum but above all thinking that I could not really understand. A part of me thinks that maybe I thought that it was nothing to do with me, even if it was a shame for her, but that would have been remarkably prescient for a nine-year old.

Here’s the obligatory new baby with sibling shot, with Sue looking very cute on the couch. That sofa, re-covered several times and resprung at least once, was in mum’s home in Marlow when she died in 1996 and was still in use at home in Santa Cruz until 2006.

After she died, I read through mum’s diaries from the time, and upon occasions when dad was away overnight on business, as he was about one night a week for his entire career, there were small indications like misplaced exclamation marks that she still wondered five years after the affair, ten years after the affair, what he was doing on those trips away. Not that mum ever confirmed the meaning of those exclamation marks. After dad died, she went out of her way to insist that he never strayed after that first terrible affair. But I know that she was at least to some degree in denial when she insisted on that, and guess that her denial eventually enveloped everything to do with dad.

But not when it first happened, not when it was all fresh and brutal and incomprehensible.

Us in Paignton, September 1955. That South Devon town on the old Great Western Railway was one of the family’s favorite holiday destinations for over 20 years.

Sue arrived in October 1954, when we were still in Cardiff, into a family poisoned and disrupted by that terrible affair. When she was six months old, during a moment of maternal inattention, the barest moment I always want to say when I tell the story, she managed to crawl off the kitchen counter where mum had left her while she was ironing and fall on her still soft skull.

I always want to, and did, excuse mum for what happened that day, but perhaps Sue never could. Her head swelled up to twice its normal size, scared both mum and dad half to death, and some time later she began to have epileptic fits, or convulsions as they were called. Sue’s fall and (perhaps consequent) fits were all reported to me. They continued throughout her childhood, finishing I was again told when she reached puberty, say 11 or 12 at the earliest, meaning that I was 13 or 14 before they stopped.

And if a kid is bouncing off walls, there’s always the harness! Harnesses were not uncommon at the time. In the background is an ad. for the film “The Egyptian,” released in 1954.

I remember absolutely nothing, not the tiniest incident or detail, about any of her fits. Now that is a personal trauma. I am literally incapable of remembering any iota of any of my little sister’s epileptic fits, despite having the capacity to reason and an often good memory during many of the ten years that she suffered from them.

What did Sue’s fits do to me? That sounds a selfish question, but handling a loved one’s convulsions is more trying than handling your own, and it must all be worse at a young age. My lovely little tortoiseshell cat Honey, also known as Pickle, whom we brought home from the animal shelter in Marlow in April 1967 with her ginger brother Tiggy, or Ginge, had fits as she got older. They were all terribly distressing. They were terribly distressing when only a cat was involved and when I was in my late teens and early twenties. Her little legs would pound uncontrollably, driving her head first at full speed into the wall or the door, again and again, as she zig-zagged wildly and crazily around. She would salivate and her eyes would lose all focus, and there was not a damned thing that any of us could do to stop it as she pounded on and on. Each fit seemed interminable, but probably only lasted a couple of minutes. We couldn’t pad the wall or the door before she crashed into it because her direction was unpredictable and could take her head-first into several solid surfaces in a matter of seconds. At least I remember these horrible events.

Of Sue’s fits, I can’t even discern an inkling. If I only knew.

Playing with dad in the back garden. He grew rhubarb and potatoes and peas and I think green beans in the various back gardens, all of which we duly ate. That was the order of things until we left Birmingham in 1966. My favorite dish from his garden was stewed rhubarb, with custard.

My best guess is that her fits made for a dreadful kind of guilt. My relationship with guilt has been one of lifelong confusion, reflecting its raw and primal nature. Like sexual desire or patriotic fervor, guilt belongs to the family of base feelings modulated with difficulty by intellect or experience. I have always had trouble identifying or recognizing guilt feelings.

Yet I remember that each of us other than Sue was not supposed to excite or upset her, for fear of provoking a fit. This was the doctor’s imperative. Mum and dad were old enough to understand the limits of their own responsibility for breaking that rule. I was not. Mum and dad knew that Sue could have a fit even if no-one broke the rule. I did not. Plus she was my little sister, just 22 months younger. How could I avoid exciting and upsetting her! Whichever way I look at it now, I must have believed that I was at fault for pretty much all of Sue’s fits that I saw. Did she literally bounce off walls like Pickle? Or foam at the mouth like a spastic in a B movie? If I only knew, perhaps that would mean that I had finally forgiven myself.

Chubby chops! This portrait has printed on its back: “Gainsborough Studio, 35 Park Place, Cardiff.” Mum and dad found a way to afford the occasional professional portrait.

Looking back at this unremembered past, the tapestry of my first few years woven with mum and dad’s memories and not my own, I am saddened by the absence of color and dreams. Where are the savors and sounds, the feelings and the music? Instead of walks in the park or stories of my first step, infancy was made up of paternal treachery and maternal anguish. Instead of stories about siblings playing, I heard about Sue’s terrible fall off the draining board and ensuing convulsions.

Out of all the hundreds or thousands of possible worlds that mum and dad could have created, the stories that remain are the regrettable errors of their lives. Those errors became more important than anything else, certainly more important than Sue and me, and reduced the first years of my life to their bad feelings. I didn’t realize it until I started working on these memoirs, but the picture that mum and dad drew of the years that I don’t remember was rather empty, a black and white image of a grey time.

They were young and in love: it was the beginning of their lives together, after the war had ended, and where was all the joy?

The effects of these early family dramas on adolescence and adulthood can only be imagined. But it is not only, or even principally, the older child’s reaction that appears in later years to the family drama of infancy. That much is under the older child’s control, at least as far as he or she remembers. It is the infant’s reaction that counts.

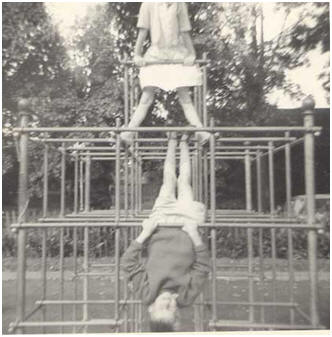

This may well have been taken later, judging from Sue’s and my size, but it illustrates the kind of climbing frames that we loved from day one and were then found in parks and school playgrounds.

I suspect that what I was not told about the era influenced me more than the stories I was told. I was raised by a betrayed mother, a beautiful young woman who hurt every day for years, to be precise my formative years, because of her husband’s follies, and that was the essence of my home environment.

No story could adequately describe that, or how she felt or how often. How much pain another’s infidelity can bring! I can only imagine her rage at dad’s unfaithfulness, the emotional distance and incomprehension that she must have felt. And dad was certainly no better off. He was decent at the core, and would have been going through the soul-destroying guilt that the affair left in its wake. Then he too will have not understood her distance from him, emotionally and the rest. Maybe mum was constantly worrying about dad relapsing, maybe dad was embittered by her coldness, and then Sue’s convulsions arrived. More guilt, more self-blame and inevitably more or less spoken reproaches. Their beloved daughter was having fits.

Inflict all those emotions on a little boy, and watch him bounce off the walls! That must have been what I did. My early hyperactivity was another part of our family history, in the role of a curse more than a blessing. Close to the angels, I was not! The curse continued through adolescence and beyond. I don’t remember it during infancy, but that must have been how it was. I have always been emotional and empathic. Add in the natural osmosis of a child, and I will have picked up on all those intense emotions flowing around the family.

A theme of modern times has sneaked into these explanations: I was the way I was not because of character but because of externally inflicted stress. We all examine what we do for ways to blame it on any of the significant others in our lives, whatever it is, from simple anger or impatience to infidelity or perversion. The legal system accepts some of these excuses, sociology validates more of them, and psychology understands them all.

Here we are in Cardiff in 1955 with Peter Whitton, Ron and Margaret’s first born, who visited on a bicycle during a summer’s ride around the Southwest, or was it Wales? Peter must have been about 15 or 16. As a young man, he was always kind to his little cousins.

But ultimately, I must hold myself responsible for who I am and who I have become. If not, there’s no motivation to better myself. That is the problem with blaming others: what you do yourself becomes irrelevant. Then again, on the way to assuming responsibility, it does help to understand where particular traits came from. Not all empathic people are hyperactive as children, or bounce off walls as adults. The emotional environment of my infancy did play a role.

Hyperactivity brings its own consequences, the typically negative reactions of those around you. Needless to say, I barely remember these either, but they will likely have compounded the bouncing around. How discipline was back then, how punishment was back then, is almost a complete mystery to me now.

There is one memory, one glimpse in my mind’s eye of mum cutting Sue’s hair in the kitchen one day, but no discernible pattern. I must have been bothering her. I must have been bouncing off walls and driving her crazy. I don’t remember bothering her, driving her crazy, but it is the only way to make sense of what followed. She flew into a rage, yelling at me to the point that she messed up her hair from shaking her head from side to side and bouncing it up and down as she yelled, and finally threw the hairbrush at me. I ducked and she missed, but I doubt that my ducking caused her to miss. She was so worked up that she could not have hit a wall! I remember thinking that it was very odd that she threw the hairbrush at me, and obviously a mistake because it broke on the linoleum floor. Mum flew off the handle and then its handle broke off her hairbrush! I asked myself what had gotten into her. We all quieted down, in my case without realizing that I had been worked up. Mum fixed her own hair and got on with Sue’s haircut. We used that broken hairbrush with its truncated handle for years later, a silent testimony to childish emotion and maternal

rage.

My only glimpses of the normal course of discipline are indirect, filtered. I tended to smack my own children, and had moments of excess, losing my temper even with a small child. My guess is that I learned that off mum. It certainly wasn’t from dad, whose anger was rare and when it finally appeared cold and biting, not venomous or expressive. My children have remained relatively difficult to discipline, suggesting that my bouts of temper and the punishments that they received were not enough to force them into submission. That does not appear to have been the case for Sue and me. Our rooms were always clean and tidy, things were always picked up and put away, and as a teenager I vacuumed the whole house, upstairs and down, the edges and the carpet, the tiles and the linoleum, once a week.

In short, whatever was done to Sue and me sufficed to make us submit and behave by the time we reached the age of reason. Not complete submission: anyone who has ever raised a child will know that total submission is unachievable, but at our house my guess is that great efforts were made in that direction, with a fair bit of success. That probably was not easy. How did mum obtain that submission? I remember that once she was pursuing me around the living room in Shirley with a cane in her hands, threatening to use it if I didn’t do this or that, but she never did. She couldn’t go that far. How did she go far enough to keep me in line? I suspect through constant and unrelenting pressure. That’s my best guess as to how it was at home.

Hopkinson’s Electric Company, dad’s employer in Cardiff, laid him off, although you can’t tell that from the photo, which was taken professionally at the departure party they organized for him. They gave him that radio, which became the family transistor radio, back when you could physically see transistors and it only took a few of them to make a radio. It must have been six or seven years later when a thief broke into our Ford Anglia when we were at the cinema in Birmingham and stole that radio off the back seat, where it lay for all to see (no car radios yet).

Another reason for parental discipline was that I lived for physical activity. My favorite games throughout childhood were principally expressions of agility. Climbing trees was a constant challenge that never abated, even after I hurt myself jumping down to the ground from too high a branch. The metal climbing frames in playgrounds and parks preoccupied me for a while, but became less interesting relatively quickly as mastering them became less difficult. I ran and bicycled all that I could, and was constantly at some sort of risk.

While anything more than cuts and bruises was a rarity, some of the excessive agility was, inevitably, misplaced. There was the time that I tried to jump up the stairs on my knees without using my hands. How I made one step is beyond me: try it and you’ll see what I mean. I was about five years old. After successfully going up three or four steps in this manner, my knees slipped off the next step up. My hands were behind my back so that I would not use them to brace myself: I took seriously the challenges I set. When my head jerked forward and down as my body followed my slipping knees down, my mouth rammed into a higher step. Blood everywhere, and five or six front teeth were bent back into my mouth. Mum rushed us to see Mr. Cheffins, our dentist, where all of those precious front teeth were removed, leaving me with an enormous hole in my smile for years, because the second teeth were in no rush to break through. One stupid mistake gave me over time a serious dose of self-consciousness about my gap-toothed smile.

Mum was constantly averting minor catastrophes like that. I have photos of my being in a harness when mum took me shopping with her when I was two or three years old. She did not do that for long, but must have felt herself to be under great pressure to do so. When she talked about it in later years, she was clearly embarrassed. But Sue had already had a serious accident: mum was not going to have another on her conscience, and I was always and constantly an accident waiting to happen. The teeth on the stairs accident was, as it turned out, the worst of my childhood, but the constant possibility, threat even, of others fretted mum for years.

Bouncing off walls is a part of who I was and of who I am. It has never changed, even as I entered middle age. I don’t know now what to do with it at times, although I’ve obviously learned a great deal about managing it over the years. How I handled it then is opaque. I doubt that I handled it at all, and suspect that mum handled it all. There are too many anecdotes showing how she reacted to it, too much that proves that it drove her crazy. I may have just been a small boy having fun, but the indications are that it was pretty much torture for mum. The indications are also that she got even, as parents do, by using parental pressure to restrain me. We’re arriving at a pretty vicious circle here.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 3 Daily Life in a Small World

Previous chapter: Chapter 1 “I have a photograph”