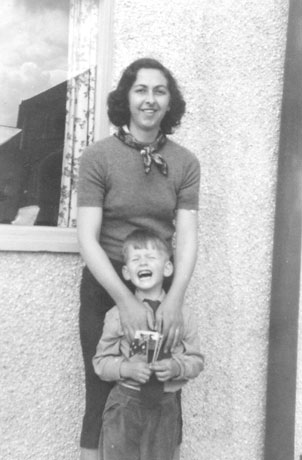

Still bouncing off walls. May 1957, in Downend, Bristol. I was four years old.

It is hard to focus on the mundane, our day-to-day life during those early years. Again, what was passed down to the next generation, Sue and me, was predominantly the emotions happening around us during infancy, the parental passion plays. Now that’s a thought: did Sue hear the same stories as I heard, or was she shielded from them because she was a girl or because she should not be upset?

Day to day life was a side show to these passion plays. We rented a semi-detached home in Cardiff after leaving Grandma Stock’s semi in Slough in 1953. Having been widowed in 1944, Grandma did not have the means to help mum and dad with a down payment even though dad was an only child. Mum was orphaned in 1944, and very little if anything was left from her side of the family. Her father’s home had been sold and the proceeds divided among his four children. I never did learn what happened to mum’s share. Mum and dad were children of industrial England, the chemicals and the grime, and of that terrible war. For all practical purposes, each inherited essentially nothing. They would need a windfall to be able to make a deposit on their own home. In the meantime they would pay rent. We had no car.

Were we cute, or what!! This school photo probably comes from Westerleigh Road School in Downend. Based on our faces, I’d guess that it dates from 1959, when Sue was 4 or 5 and I was 6 or 7.

A Cardiff memory that remains, and there are not many, involves more worry about Sue. One beautiful summer Sunday, dad took her and me to an enormous wide sandy beach, perhaps at Barry Island, for one of the proverbial visits to the seaside that was then at the heart of enjoying summer for the great majority of Britons. Of course, it was the kind of summer Sunday that brought out every other family in South Wales with the same purpose, and somehow in the middle of that interminable throng Sue got lost. At the time, I could not imagine how dad managed to lose her, or even how I had managed to lose her, but having lost a child myself I now know how easy it is. Dad and I were looking for her, together of course so that I couldn’t get lost as well, walking carefully and thoroughly up and down and along the beach: I could tell that he was carving the beach up in his mind so as to survey it accurately and completely. But even with his thorough approach, it took what felt like hours to find her. I was so worried. I remember that dad had his urgent and distant expression on as we carefully made our way back and forth through the crowds. I peered to left and right as he did, very worried. That is how it was when we were little and she was my little sister: I always seemed to be worried about Sue. I also remember the white semi-detached house we lived in in Cardiff, and a little girl across the street, but not a lot more.

We left South Wales when dad was laid off, and moved house in 1956 or ’57 to just outside Bristol, in Southwest England not a long way from Cardiff, where again dad found a better job. The lay-off payment became the windfall that mum and dad needed to buy their own home, and was the down-payment on 2, Amberly Close in Downend, Bristol, another semi-detached house. They owned their first home. They tried to own a car too, a black 1953 Ford Anglia with the license plate number RAE 534 that they bought in 1960, late during our stay in Bristol, but dad told me later that it almost broke them.

Mum’s diaries for these years often list every penny that she spent, on groceries, bus fare, wool for knitting Sue and me clothes and darning dad’s socks, everything. Almost fifteen years after the war, and with dad advancing reliably in his profession, this was still post-war England. My family had no car until I was seven or eight, and when we finally bought one it almost broke us.

Here they are, for those of you who missed this classic British cultural icon. It’s Bill and Ben, Flower Pot Men, and their friend Weed, presented by BBC TV as a part of their “Watch with Mother” series, based on, you guessed it, their earlier “Listen with Mother” Series carried by BBC radio. TV was easy for the BBC back then: it was radio with pictures!

Mum washed our clothes in the sink, scrubbing and rubbing them until the dirt was out, which she gauged by sight, and then wringing them out through the manual wringer that fitted onto the side of the sink. It was strenuous work, hard work, especially cranking the wringer, which took all mum’s strength. Housework involved more real work before the labor-saving devices came along. Drying involved hanging each item on the line across the back garden, a marketing phrase to describe the minimal lawn and verges behind the house, and the cooperation of notoriously unreliable English weather.

Drying laundry was a pantomime that repeated itself incessantly. Mum would worry out loud about when to do the washing, sometimes for days at a time, so that when it was done it could dry without being rained on, and then when it was hanging on the line would complain that it looked like rain and why couldn’t those forecasters get it right sometimes? Half the time, literally, she would have to run out into the garden and haul it all in again until the rain stopped. Needless to say, we did not change our clothes that often, perhaps once a week unless a football accident happened (dirt on the shirt!), which was severely sanctioned. No washing machine or dryer or toaster or fridge, but we did rent a television.

Again from May 1957, one of the few rolls of film on the back of which someone (it looks like Grandma’s writing) kindly wrote the date. Don’t know where it was taken.

Recognizing that the cost of a television was prohibitive for the many English families who ardently desired one, several companies sprang up to rent TVs at a very reasonable monthly fee. Ours was small and black and white, and the BBC was only slowly learning to master the medium, especially when it came to children’s programming. My earliest TV memories are of Bill and Ben, the flowerpot men, oddly articulated creatures, perhaps puppets, who lived, you guessed it, in flowerpots, which they would pop out of periodically to commune with Weed, who lived nearby and spoke with an excessively feminine and nasal whine. Only serious boredom could compel me to watch daytime TV, which only started about three or four in the afternoon in any event. Our paternalistic government was protecting its tender charges from too much TV, or at least that’s what I remember. Perhaps the BBC simply did not have the money to produce or purchase more programs. Nowadays, I drive our children crazy implementing similar restrictions, although at the beginning of the 21st century there are many more enjoyable and interesting shows for children.

Christmas at the Broughty Ferry Hotel in Bournemouth, I think in 1959, when mum’s diary refers to a trip to Bournemouth. Holidays were a great time, and the cameras come out. These two photos (one more below) were taken by a professional at the hotel. There’s a lot to be seen here: the expressions of the other man and dad, the older lady behind, mum almost out of the photo, the cigarette in dad’s left hand. “Every picture tells a story, don’t it?” © Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood

My first consistent memories of childhood date from our years in Bristol. The principal difference between infancy and the years that I remember is that the existence of memory is likely to mislead me into believing that I really knew what was happening. Not so. First, the earlier an experience, the more I find it hard to distinguish my own memory of it from someone else’s report of it. Second, even my own memory is bedeviled by what has been built onto it subsequently, by layer upon layer of interpretation and confusion. And third, every memory is distorted because of prejudices or beliefs, and mine have evolved over time. I remember different times in different ways at different times, with the filter of the present changing as much as the salient events of the remembered past.

My stronger Bristol memories tend to be of the night, of the darkness and the small feelings it brought on, of the fear of the dark and what it might contain. Those feelings of being small were so prevalent back then, which makes sense if you think about it: I was small! Every day, or almost every day, I learned to deal with those feelings and cope with them, with less effort and anxiety as time went on. As an adult looking back, it’s hard to relate to feelings of being small or understand where they came from in our cozy semi-detached little home. For one thing, the house was always carefully locked, whether we were home or not. For another, all the rooms were intimately familiar and well-explored, as were all of the spaces in them, under the beds, behind the sofa, in the cupboards. I explored everything rigorously, in the daytime. And mum and dad were either in the room or in the next room or just downstairs. But there it was, small feelings in my cozy little home every time darkness fell.

It was cold in the house most of the year, and it was colder in the bedrooms than in the kitchen or living room. There was no central heating. The coal-fired fireplace was in the kitchen, I think, but perhaps it was the living room. Logically, it was where we spent most of our time at home. Dad’s first task every day through the most of three seasons a year was lighting the fire so that we could get up and warm up. The fire was made up of coal on sticks of wood laying on crumpled newspaper to start it all burning. It took a lot of maintenance, carrying in the coal and the wood, crumpling the newspaper, and cleaning the embers out of the grate. But it gave off a heart-warming deep heat. We also had an electric heater, one of those burning hot radiating coils of wire that reflects and radiates heat for about two yards in front of it, but no further and nowhere else, and always is either too hot, if you’re close to it, or too cold if you’re not. We moved it around to where we needed it. So the bathroom was warmed for our weekly bath and for washing our hands and face in the mornings. Downstairs was comprised of the living room and the kitchen, neither particularly spacious, and once the coal fire warmed through, it was warm downstairs. All the fire then needed was more coal.

Here’s mum during the same holiday in Bournemouth, getting into the spirit of the thing. Does she look watchful? Or is it me? How about the little girl’s glowering expression? There’s another cigarette (they were everywhere then) in the left hand of the man in the middle.

But our respective bedrooms were not heated. Going to bed was rushed and shivery. I had several blankets for warmth, and several stuffed animals for comfort. The stuffed animals were arranged in a constant order around my head on the pillow. I forget exactly which little creature was where, but they were all laid out next to me, and my stalwart, stuffed pony was always laid behind my head to protect the rear. That was how I looked on it. He was the biggest, and I was the most vulnerable from the rear, because I could not see backwards. I lay there after mum kissed me goodnight, slowly warming up the incredibly fresh and cold bed with my content:encoded, and I would check that the pony was in his place and stop worrying about what could come at me from behind. Except for earwigs. My big fear was earwigs. I had heard somewhere that an earwig could burrow its way into your ear and across your very brain and out the other side. It seemed terribly savage, and it was difficult to imagine how such a thing could happen in England, but I worried and worried about those earwigs. That was definitely not how I wanted to die. I always ensured that the blankets covered my head. My bed was a fortress, with the little stuffed animals in front, my stalwart pony behind and the blankets over my head.

My nights had one regular interruption, right around the time that mum and dad went to bed. One of them would gently wake me up and lead me to the bathroom, where I would dutifully and half-awake take a leak. One night when they were out and a babysitter was looking after us I woke up covered with sweat, all over my body it seemed. I examined the question and my wet pajamas, and thought it over and thought it through. Right around the time when mum and dad came home, I finally figured out that it was not sweat at all. The babysitter had not been warned to give me my nightly break, I suppose because mum and dad were coming home anyway. But it was a weekend night, and they came home much later than their normal bedtime. The wet pajamas were quickly changed.

St Joseph’s School, Fishponds (really!) in Bristol. The first school I remember. Mum obligingly drew a circle around my head to help us identify who I used to be. Very few memories of that school, none of other children. Two boys were good friends in Bristol, Nigel Scutt from around the corner in Downend, and Michael Palmer, a bike ride away in Frenchay past the enthralling sewage plant at the bottom of the hill.

Despite the tight purse-strings, Bristol was the start of happier times for this young family. Dad had played field hockey for Slough Grammar School and then at the London School of Economics, and in Bristol he started playing hockey again for a club called Henleaze, and mum and he made a lot of friends through the club. They made friends at Henleaze who lasted the rest of their lives. They have all moved on now, long gone, but I still exchange Christmas cards with one of the couples that they befriended, Brian and Moreen

Newman, who in 2007 still lived near Bristol. Mum and dad found the money to go out as a foursome or invite people over, for hors d’oeuvres rather than a meal to conserve the precious pennies. The vivacious dialogue that they maintained for the rest of their married lives, whatever their ups and downs, had begun. I remember the fights too, the arguments and squabbles, but the communion that characterized most of their marriage had also arrived.

One flash of memory of mum and dad in Bristol has stayed with me, perhaps embellished as it was rerun over the years or by the adolescent poem that I wrote about it, but too simple to be overly deformed. All four of us were walking in the neighborhood in Bristol one sunny summer afternoon. Sue and I were running around and playing ahead of mum and dad. We almost always did that. They would walk, and we would run around them, hiding in doorways or behind bushes, non-stop scampering back and forth. The flash occurs when I looked back at them, walking arm in arm in the sunshine. Mum was so slim in those days, and she was wearing a white cardigan draped over her shoulders, her black hair bouncing on it. Dad had a white shirt on too, but of course his hair was short, only a little longer than the military length of his service in World War II, and pulled back off his forehead as he always wore it. They both smiled at Sue and me, as I teased them about holding hands. Whatever the bitterness or mutual recriminations of their later years, and there were plenty, those moments of delight in each other’s company never faded completely. Perhaps there was the occasional long delay before they resurfaced again, but they always resurfaced.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 4 The English Riviera

Previous chapter: Chapter 2 Daily Life in a Small World