Sounds easy doesn’t it? But it took more than three years for our furniture to move from La Bellanderie to Santa Cruz. Why?

This used to be a nice, solid inner-spring sofabed. It cost about $1,000 in New York City in 1983, and had lasted several house moves, including one international move, but not the Tison treatment. It’s here at the top of the page because it really was strongly built piece of furniture, and yet its back was broken. An accident?

First and most importantly, Tison S.A., the furniture moving company based in Coignières (78), west of Paris, which Marie-Hélène picked to do the move for us, was crooked. In trying to con us in 1997, Tison succeeded in depriving our children of all their toys and most of their clothes for over three years. Its President, the chief con artist, was one Arnauld Bourlé. There are several examples of Arnauld’s con artistry on this page.

After realizing that we were being conned, and to help us recover our furniture, we called in “La Chambre Syndicale du Déménagement,” a French self-regulatory organization. As one of this association’s jobs is to protect moving company customers, and as our furniture was being held for ransom by Arnauld Bourlé in Tison’s warehouse to blackmail us into paying amounts that should never have been due, we asked them for help. We told them basically what is on this page, explaining Bourlé’s various cons to them. Associations like these typically know who their bad apples are, and know what the basic cons are. It is their job to know. The Chambre Syndicale did absolutely nothing for us.

Our final fallback, after all was delivered with the inevitable damage of three years of being moved around, was SIACI, a French insurer of goods in transit, now called DiotSIACI (I think). We had paid substantial premiums to SIACI (to the tune of about $1,500!) to insure our furniture in transit. They weaseled and schemed and stalled and finally did not pay us one red cent in compensation, despite all the damage we had suffered in diverse ways.

* * *

Here’s more detail. We were trying to do a lot in a short time. Our wedding was on May 24th, and we were scheduled to fly to New York on June 23rd. As always happens when you’re self-employed, work picks up when you need more time for personal matters (no complaints there: it pays the bills), and I barely had enough time to do everything.

The major collective task was packing and arranging to move our furniture to California. I had accumulated mine from my my own home (what Sunshine left behind when she moved out), from my mother’s house after she died and from Great Aunt Alice. Marie-Hélène had accumulated hers from her mother after she died, from her apartment shared with Pierre, and from her Tante Lucette.

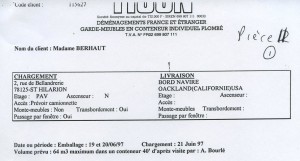

The famous Tison estimate for a maximum of 64 cubic meters of furniture, “in the opinion of Arnauld Bourlé.”

In short, we had a lot of furniture by this time, in a big house. We didn’t yet have a home to move it to, but were counting on having all the furniture delivered to the Port of Oakland and having it collected by a local moving and storage company once we’d found a place. A bit messy, but not too bad, all things considered. The cost risk we thought was manageable, the warehousing in Oakland or Santa Cruz.

The overall con evolved slowly, inexorably. With the gift of hindsight, it was all so clear. Sitting in our bare and empty house in Santa Cruz, looking at the documents and trying to get our furniture back from Tison’s warehouse, where it was being held hostage, it became clearer and clearer.

Arnauld Bourlé sweet talked Marie-Hélène and gave her an estimate for loading a container and shipping it to Oakland. I was in Paris working the day that he visited to make his estimate. It was a little lower in price than the other estimate that we obtained, although not much. We had used the other company before, and had been satisfied. But expenses were mounting up, and price won the day. We paid Tison the two requested deposits.

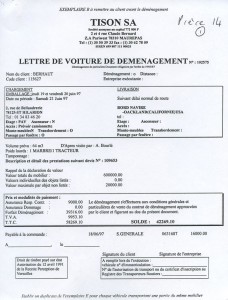

VAT is called TVA in French. It is one of the line items in the box lower left. If we had paid that almost 10,000 francs on the day that we left, Tison would have had no duty to pay any of it to the government. In short, Bourlé would have made another 10,000 francs for nothing. Of course, it would have been a fraud, but not the only one in this story.

The estimate itself read “volume of 64 cubic meters maximum in a 40 foot container, according to Mr Bourlé’s visit.” Marie-Hélène, who had escorted Bourlé around La Bellanderie, told me that he had expressed a little concern that perhaps we had a bit more furniture than the 40 foot container would hold. We had been planning on leaving some things in France in any event, things like appliances that would not work on US electricity, and arranged with Bourlé for 10 cubic meters to be shipped to Marie-Hélène’s Oncle Alain in Autun. As Bourlé had confirmed a volume of 64 cubic meters in writing, we felt comfortable that arranging to take an additional 10 elsewhere would cover us against any underestimate of the volume.

Then on the final day of the move (the men were in the house packing for three days altogether), amid the insanity of trying to inventory and complete the packing of a 4000 square foot home, Bourlé’s men “discovered” that all did not fit in the 40 foot container supplied, even when 10 cubic meters was separated out and loaded into a separate van for delivery to Autun.

The men did not appear to be at all surprised.

This was Charlie’s changing table before we left. Of course, by the time it was delivered, over three years later, Charlie no longer needed to be changed. We had to buy another one for Alex while we were waiting for delivery of this one. In a way, you could say the fact that it was broken in transit didn’t matter.

We were frazzled and worried because not everything had made it into the container, but still aware enough not to pay all of the balance. Our alarms were going off. We paid the rest of the cost for Autun (all that left correctly, if without the inventory that Tison was supposed to prepare), but withheld 10,000 francs of the US balance (about $1600) pending clarification.

Two other events at the end of that frazzled day added to the number of alarm bells ringing in our heads. First, the final invoice for the US shipment added VAT, which was not due on a shipment to the US. If I wasn’t a business lawyer with some familiarity with VAT, I would never have known that. As it was, I ignored the 10,000 francs (again about $1,600) in VAT when calculating what to pay. Imagine someone less versed in the intricacies of French taxation, confronted with an invoice at the end of an insane day of organizing and separating and packing: that person would likely have paid it in full. Arnauld Bourlé apparently had several possible cons covered. If one or two failed, he had more up his sleeve.

The second event completed the day. Bourlé had asked us to obtain export documents from the appropriate government agencies and have them ready to give to his driver when he left pulling the container. The principal document was (and you could have guessed this!) confirmation from the local fisc that we had paid all taxes due. The driver refused the documents, which we had scurried around collecting, as did his men. We asked the British Airways counter person at Heathrow Airport in London (our flights went CDG-LHR, and LHR to JFK) to send them for us as we rushed through on our way to New York. They did get to Tison, although Bourlé of course claimed the contrary.

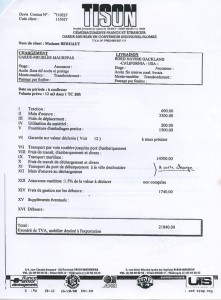

Here’s one of the first invoices we received after arrival in California. Bourlé got this one to us fast! It covers only the additional 20 foot container that Tison was insisting we would need to pay for. $3,500.

Upon arrival in California we received faxes and registered letters billing us for one or other (or more) of (1) the additional 20 foot container that would be needed, said the letter, to ship the balance of the furniture for Oakland that did not fit in the 40 foot container, (2) shipment of the initial 40 foot container to Le Havre (where it could not be loaded onto a vessel because of the “missing” customs documents) and back, and (3) storage of our furniture at Tison’s warehouse (where it was never supposed to go) during the ensuing period.

The amounts being invoiced were pretty significant. We had paid 38,000 plus francs toward the estimated 48,000 plus francs for the US move (and 5,000 francs for the move to Autun). Just the additional 20 foot container was going to cost us an additional 21,840 francs (excluding insurance), around $3,500. The back and forth to Le Havre of the original container was invoiced at over 23,000 francs (almost $4,000). Another 15,000 francs (about $2,500) covered “deposit of the container in our warehouse” and the first two months of storage there.

That’s $10,000, on top of the initial $8,000 that we had paid! Then we started receiving regular invoices for storage, invoices that increased every month.

Would Tison have settled in late 1997 for an amount below the aggregate of these early invoices? Perhaps. But the amounts were just too high, it took me nine months to find a real job in California and the balance of mum’s estate, which I had been using to cover emergencies such as this, had been the deposit on our home. We simply didn’t have the $6-7,000 that such a settlement might have arrived at. It wasn’t worth trying for.

Whoops! This was actually more serious than it looks. Several of these dark glass doors were broken or cracked, rendering unusable the entire (rather nice) piece of furniture of which they were a part.

Plus, I have to admit that I was furious and in no mind to accept this kind of blackmail. It offended the English part of me. As we got further into the dispute, the extent of Arnauld Bourlé’s deliberate and planned cheating became clearer, and infuriated me.

Here was the basic con. Immediately we contacted Tison, right around the time he visited La Bellanderie to give his estimate, Bourlé asked his shipping agent in Le Havre for a quote for 85 cubic meters of furniture to the Port of Oakland. Unbeknownst to us, the agent apparently gave him that estimate.

In early July after we arrived in California, Bourlé explained in a fax that his written estimate to us of 64 cubic meters, the amount that he said fit in a 40 foot container, resulted from Marie-Hélène’s request to him to limit what we shipped to the US to 64 cubic meters to fit in that container. She had not wanted to pay the excess for the balance, his letter explained. If that excess was the $3,500 he claimed in his simultaneous invoices, that might have been logical. In light of the final amount that we paid for the excess, and why it was so much lower at the end, her alleged request made no sense. But I’m jumping the gun!

Even then, this basic con did not appear to be a very good one. The language that Bourlé used in his estimate made it clear that it was his estimate (“according to Mr. Bourlé’s visit”), and did not mention any limit on the volume made at the request of his client. He obviously should have made such a mention, along the lines of “total volume = 85 cubic meters; volume for shipment = 64 cubic meters, as requested by client.”

Otherwise, what was to protect his company against any claim from us based on his own blatant error in the written estimate that we received? Of course, he couldn’t have written enough to protect his company at the time, because that would have alerted us in advance to the con. The language that he actually used was proof of the con for anyone bright enough to see it.

There are other common sense arguments that revealed the con. What woman who is emigrating will ask that one quarter of her personal effects be left in limbo, even to save a few thousand bucks? Wouldn’t she have obtained an estimate for storing or shipping this quarter elsewhere? Well, guess what, she did arrange for shipment elsewhere of more than she believed would be left out of the container. (By way of a sidebar, most of what was shipped to Autun, apart from the French appliances, was my stuff that Marie-Hélène didn’t like: this was normal feminine behavior!) She didn’t arrange for more to be shipped to Autun or put into storage because we had no idea of the total volume.

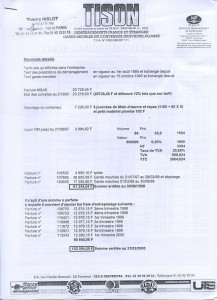

Check this out! The final Tison invoice (March 2000) before the court entered its judgment: over $25,000!! On top of the $8,000 that we’d already paid back in 1997!

But ultimately common sense didn’t matter. The mere fact of preparing his con by having his shipping agent give him an estimate for 85 cubic meters caused the court to believe Bourlé, on that topic at least. This was not the smartest court in the world. Neither was it the fastest. How long did it take this Versailles court to order Tison to deliver our furniture? Almost three years!

We had tried for a more urgent decision from the Court, seeking an order early on that the furniture be moved here promptly pending resolution of the dispute. But the Court had found questions of fact to be resolved, and thus refused to order the furniture to be sent until full exposure of these facts. So we waited for three years.

But I shouldn’t badmouth the court. It did smell a fairly hefty rat here, the diminutive and dapper M. Arnauld Bourlé! That was Marie-Hélène’s description: I never met the man. It found that he had lacked diligence in obtaining the required customs documents from us. I’ll say: having his own people refuse them certainly lacks something!

Accordingly, the court held each of us and them half responsible for what happened and ordered us to pay Tison an additional $1,500 for delivery of the 64 cubic meters. You could hear the sigh of relief all over Santa Cruz! Of a final invoice of $25,000, we only had to pay $1,500. If that’s how you split the difference, I’m all for it!

My dad brought five of these century-old English contracts home from his office while I was at law school: nice touch! They were contracts from his company’s past. Mum framed them so that both front and back were visible. Not a cheap framing job. Fortunately, only one of the five was broken by Tison.

Which brings us to the final con, or should I say the final element of the first con. Throughout the process, Tison claimed payment for an additional 20 foot container to move to the US the balance of our stuff that would not fit in the initial 40 foot container. We discovered soon after our arrival in Santa Cruz that there was such a thing as a “high top” container, and we later ascertained that it holds about 76 cubic meters. Doing the math in our case, assuming as Tison claimed after the event that there were 85 cubic meters of furniture in our home, after 10 moved to Autun that left 75. Did we need a second container? No, all should have fitted in one 40 foot “high top.”

But we didn’t know for sure until after the court’s judgment, which left the treatment of the remaining 11 cubic meters to the parties to work out. Tison, by now affiliated with UTS, a more reputable group of moving companies, proposed that we paid 4,000 francs, less than $700, to include all of our furniture in one high top container. That was explicit in their settlement proposal: we would only need to pay $600 more if the remaining 11 cubic meters was shipped with the original 64. This offer was not made by Bourlé personally, by the way.

You guessed it: all arrived in the fall of 2000 in one high top container! The whole circus had been completely unnecessary, uniquely designed to con us. Even if 85 cubic meters had been the initial estimate, then after taking out the stuff for Autun, a high top container could have taken everything as arranged to the Port of Oakland in June 1997.

To summarize the bare bones of the more serious cons: (1) there was never any need for a second container, even if Bourlé had told us about the 85 cubic meters as well as his shipping agent, just a higher container of marginally more expensive cost, (2) refusing or losing the export documents, which required (a) shipment back and forth to Le Havre and (b) deposit of the container at the warehouse and ensuing storage charges. I doubt that shipment to Le Havre ever happened, in retrospect, because the driver refused export documents (and no driver leaves for a port without export documents) and because such a shipment would have required Tison to pay third party costs, costs which it might never obtain from us and never did in fact obtain from us. My guess is that the container went straight from La Bellanderie to Tison’s warehouse, and that the whole Le Havre story was contrived to bolster the additional amounts that Bourlé claimed from us. A reminder of those amounts: (1) about $3,500; (2)(a) about $4,000 and (2)(b), about $2,500.

* * *

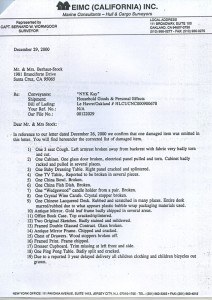

Here is the first page of the insurance company’s expert’s report on the damage the shipment suffered.

As it was, when the container arrived it was holiday time at our house! There was just so much stuff. We’d been living for so long with rented furniture, cheap things that we’d bought to tide us over until our furniture arrived and even other people’s cast-offs: we felt rich and royal as we unpacked out own things, which are themselves far from rich and royal.

It took days to move the furniture inside, weeks to empty all the myriad boxes. There were things that we’d forgotten, and things we didn’t want to remember. All of the children’s clothes had been outgrown, of course, and their toys were no longer age-appropriate.

But there was a ton of everything. I was thrilled to recover my cranky old bicycle and my old LPs and musicassettes. We all found things that felt like old friends. Music, books, posters, rugs, you name it. It was such a treat that I would plan to empty another box that evening or the coming weekend, just for the sake of it. Furnishing our home, finally, went on for months.

Every cloud has a silver lining. Marie-Hélène made a trip alone to Paris in February 2000 to help our lawyer (he had been unwell) at the court hearing. She was able to meet up with Faby, Maeve and Fiona at the airport, one day before Faby’s third daughter, Leah, was born.

It had been over three years. We had left a little food in the wardrobe boxes, not perishable, but with a view to recovering it when it arrived, in a few months. Strains of green stuff had been generated in some of the packages, which we tried not to examine as we jettisoned them!

Then there were my suits, which had all shrunk a couple of sizes despite being 100% wool. This we attributed to dampness in the warehouse where their wardrobe box had been stored. I certainly hadn’t put on any weight over those years, despite having given up smoking in January 1998!

The furniture moving was (along with our two-year separation from Nick and Tom) the bad part of moving to the US. We quickly found a lovely home on a ridge in the redwoods outside Santa Cruz, the children found a lovely school less than a mile away, and Ian found a very rewarding job where he could relearn his field in the US. Not so quickly, but soon enough.

* * *

Stories like this one always seem to have a sorry footnote. On many occasions, like this one, that sorry footnote involves an insurance company acting in bad faith.

After the furniture was delivered, we needed to deal with the damage. Not surprisingly, after having been packed and unpacked twice (from the smaller container to Tison’s warehouse, and from Tison’s warehouse to the high top container), there was some breakage. The insurance company’s own experts visited us to survey and assess the damage, and by Christmas 2000 had it all listed. How much damage did the insurance company’s own experts identify? Between $17,000 and $25,000. And that did not include the missing items, which we had a nearly impossible time remembering in the absence of a complete inventory. Did I mention that Tison’s men did not complete their inventory as they loaded? You could have guessed that too, right?!

There were odd things missing, a box of tools, a box of videocassettes, a box of crockery, that sort of thing. I’m tempted to describe it as normal wastage over three years in a warehouse. The one thing that really upset me was the box of videocassettes. Mum had recorded the Beatles’ Anthology when it played for the first time on British television in several weekly installments in 1995, the year before she died. The recordings weren’t great, and there were one or two episodes missing, but obviously they meant a lot to me. Even the replacement cost of these lost items was not included in the insurance company expert’s report.

Of course, the report also did not include all the money we had been obliged to spend outfitting the entire family and our six-bedroom home for the whole time that our furniture was withheld. Think about how much that involved.

Christmas in a house with no furniture! This was our first year there, 1997. The house remained bare, uncluttered, through September 2000.

SIACI, the insurance company, waffled and stalled and negotiated and asked for more information, estimates to repair what was damaged, that sort of thing. But they seemed in their obtuse bureaucratic way to be approaching a settlement, and that kept our guard down. Finally, when we started getting impatient and wrote yet another demand letter, we discovered that if we didn’t sue the insurer before the first anniversary of delivery, it was too late. It was too late already: SIACI had successfully waffled and stalled for a year, and now were in the clear.

* * *

The two participants in this story who are really and truly the scum of this earth, as the story itself proves, are M. Arnauld Bourlé, who takes the cake for the sheer diversity of his con artistry, and DiotSIACI. Watch out for both of them if you ever move furniture in France!