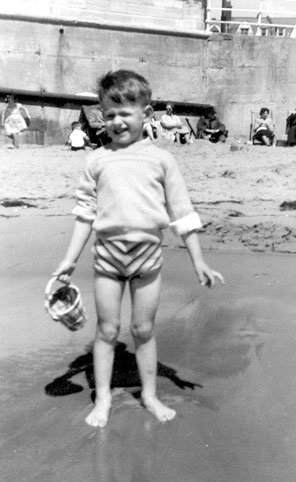

May 1957, on the beach in Paignton. The tide came in along the wall behind me and to my right.

Every Easter in Bristol and for years after, we all drove down to Paignton in Devon with Henleaze Hockey Club to join in their annual hockey festival. Paignton was the first holiday town for us, the first place that we vacationed in regularly, and it was a dream in the way that vacations are, intervals in a more routine and boring and less amusing life. The drive down was itself quite an event for us all. The A38 ran most of the way down to Paignton, and in those days it threaded its way through each and every village and town on the way down and back, a two-lane road for most of its length, almost inevitably filled to overflowing even between the crowded towns.

Dad would overtake with great verve, it seemed to me, but we were still most often stuck in traffic. It took three or four hours or more to cover about 100 miles.

Not that the trips were without interest. The very names of the towns and villages on the way were so strange and compelling. Just as when I traveled in later years, driving a long way always led me to think odd thoughts. One that preoccupied me for a while was how did the space in the car move at a different speed than the space outside? When the window was opened, the difference between inside and outside would become apparent, as it would more convincingly when something was thrown out. But otherwise each moved entirely at its own pace. As I said, odd thoughts.

Then there were the double white lines in the middle of the road that I first saw on one of those trips down the A38 to Devon. The bright new lines with cat’s eyes between them fascinated me, especially at night. They seemed to jump out at you. A single dotted line meant that you could overtake going either way, and a dotted line on one side of a solid line indicated that you could pass on the dotted side but not the other. I later realized that these new-fangled white lines, despite their impressive qualities, were a cheap fix. In the US, thousands of miles of Interstate Defense Highways were built during the fifties and sixties. In the UK, they finally got round to that construction about 20 years later. In the interim, they did what they could with the roads at their disposal, and improving the white lines was one thing that they had the money to do.

Henleaze Hockey Club, sadly defunct during the 1990s, after a game during the Paignton hockey festival held at Easter 1959. Their nickname was the uninspiring “Bluebottles,” a species of fly. Dad is standing on our left, and standing three over from him is Keith Merritt. Mum had inserted this picture at the beginning of an album starting in 1970. I wonder why.

They now refer to the South Devon coast where Paignton is located as the “English Riviera.” This is wishful thinking on the part of the tourist boards of the local towns. South Devon is perhaps 600 miles north of the French Riviera, and a whole lot wetter and colder, especially at Easter when the hockey tournament was traditionally held. But it was on the sea, and it had trains that ran almost all the way to the sea front, and we were on holiday. The few hotels were over our budget at first, but Paignton catered well to those of us below the hotel line with its row upon row of guest houses. These had bedrooms with sinks in for brushing teeth and washing behind the ears, the schoolchild’s morning ritual, and toilets and bathtubs down the hall. They served breakfast in the dining room and sometimes dinner, and although there was not a lot of choice the dining room normally had a relaxed and comfortable atmosphere: not a lot of money or pretense in a guest house.

We moved up in later years to the Hotel Redcliffe, the only hotel literally on the beach at Paignton, with its complete en-suite bathrooms, full and varied menus, table tennis room and even a real tunnel to the beach. The tunnel entrance was hidden behind curtains in the lobby, and it led down stairs hewn in rock and then along a damp and whitewashed corridor in the rock directly down to a very solid wood door adorned with thick, rusting hinges six foot above the sand on the beach. They had to close the door when there were storms to prevent the waves breaking into the tunnel. Needless to say, that tunnel was a schoolboy’s dream. But the Redcliffe never had the same relaxation and comfort as those guest houses with the toilets down the hall.

Except for us, of course: we were the same wherever we were.

Mum took care of that. Her parents were both of Irish origin, and she was truly Irish. Her feelings were all over the place, and not so much worn as paraded on her sleeve. Her laugh was pure joy, and rang through the room like a Christmas carol. She loved to laugh. I remember wishing that the floor would open up and swallow me when, during one of those sensitive childhood periods when embarrassment came all too easily, she let out peals of laughter in the cinema next to Sue and me. She could no more easily fake what she felt than hide it. I am sure that the same effusive and barely controlled self-expression spread her feelings of betrayal and pain after dad’s early straying. As those troubled days receded, and life went on as life will do, mum’s feelings bursting all over the place transformed the mundane and day-to-day of our lives together.

Dad was pure English, intellect and control. His feelings were frequently locked inside where they could do no harm, regardless of what good they might have done him. Fear of your own feelings is a terrible burden, a sorry deprivation. Without mum, he might have slowly deteriorated into a baleful rigidity, a sadder kind of solitude. With her, he became one of the family, sometimes reflective, sometimes playful, always alive.

A photo ripe with meaning: dad stood next to Keith for a team photo after a Henleaze match in Paignton on April 17, 1960, one day after mum and dad’s eleventh wedding anniversary. Coincidence? I don’t think so!

Paignton gave us a red letter event in our modest little history, this one mum’s. She had an admirer in Henleaze Hockey Club! As I write the words now I still find this shocking. Maybe a boy must avoid seeing his mother that way after he reaches a certain age. Maybe it is simply that she loved dad so much. But that admirer still shocks me the way that it shocked me when she first told me about him years later in Birmingham. But she danced with him in Paignton one year, and after one of her dance evenings he made his “declaration,” as the French say. She loved to dance, mum, and dad did not, so she would dance with friends. Keith was one of those friends. After he had told her how much he loved her, after he had offered to leave his wife and children to be with her and help her raise Sue and me, mum was in her own words “more astonished than anything else.” She couldn’t believe that he had fallen in love with her, that his friendly little visits to her house in Bristol and her dances with him meant that much. I could have warned her about the dances. She sometimes wore a full black skirt to dance, with vivid red and yellow flowers that made her look like a wild and graceful gypsy when she twirled, and she loved to twirl.

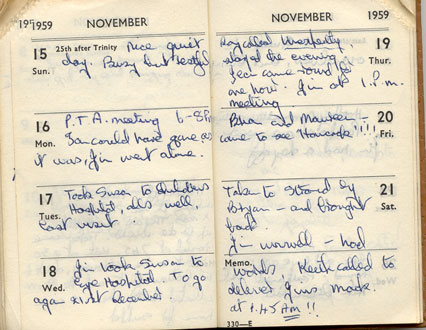

A page of mum’s 1959 diary. Check out the entry bottom right: after noting that she and dad “had words,” and there are very few entries like that in her diaries, “Keith called to deliver Jim’s mack (or macintosh) at 1.45 AM!!” Tell me that she didn’t know that something was happening!

Keith hosted the only Christmas away from home that I remember outside of a hotel. For us as a family, that was almost a contradiction in terms. To make matters worse, I got the flu for Christmas. The fever disoriented, the strange surroundings disoriented, and even the sack of wonderful and thoughtful presents could not make it work. Keith hosted the only childhood Christmas I remember that did not work. Dad told us all later that he knew about Keith’s intentions way before mum found out: Merry Christmas everyone!

Of course, mum was obliged by her circumstances to let Keith down easily, and she duly did so, professing her astonishment again and again, and almost overnight retrieved her self-confidence. The way she told it, it was Keith who finally convinced her that she was worth something after dad’s initial affair in Cardiff.

And she did not even get involved with him, at least the way that she told it. Some of her diary’s exclamation marks intrigue me, however. On the day that Marie-Hélène was born, when mum was home in Bristol a month after Paignton, she wrote “Keith came to visit!!!” Three exclamation marks. Yet he made his declaration in Paignton, she always said, after one of those evenings dancing, driving around with her in his car. So what happened back home in Bristol that merited three exclamation marks if, as she also said, she had turned him down in his car in Paignton? These are things that the children are not supposed to know. But wouldn’t it be a delightful balance if the exclamation marks that seem to symbolize dad’s infidelity in her diaries served also to indicate her own? If I only knew. In any event, they were certainly an expression of an excitement and pleasure on mum’s part. I can’t help but view that excitement as being the equivalent of an affair for her even

if it never really happened, and a more meaningful equivalent at that.

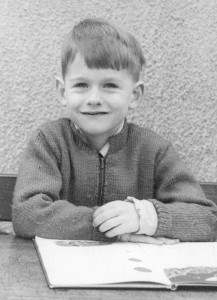

At my desk at Westerleigh Road School, Downend, between St Joseph’s and our move to Birmingham, in around 1960. Happy days! Mum knitted the cardigan.

I too had an incident at Paignton, but rather than being a red letter event it announces another of the fundamental problems with writing memoirs. Some experiences simply do not seem to be made for sharing! I am rarely put off by such niceties. Besides, I was just a child when it happened, maybe six or seven years old, and children do things that grown-ups do not. You have been warned!

My terribly embarrassing incident at Paignton started with one of the loves of my life, watching the sea. More particularly, when I was young, I loved to watch the tide come in, the waves creeping up the beach, constantly advancing where no waves had gone before, even little waves that have almost nothing of the power of the ocean in them. Maybe I first started doing that in Paignton. I don’t remember it starting, I just remember how much I liked it. In any event, I loved to watch the tide come in.

One evening soon after arriving from Bristol, while mum and dad and Sue were settling into our guest house on the esplanade, I bugged them to take me to the promenade to watch the waves. Only lawns and walkways separated the line of guest houses facing out over the sea from the beach. It was a safe walk once they’d seen me across the road, and I needled them, as only a small boy can, to the point that they almost always walked me

across the road.

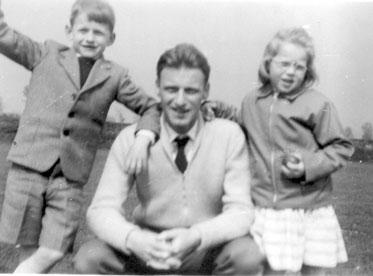

If we couldn’t make the seaside, there was always the country. Mum thought that this was taken at Clifton, downs outside of Bristol where we spent many a Sunday afternoon.

There must have been a storm out to sea that evening, or at least strong winds, because the waves coming off the English Channel were wonderful and strong, surf rolling in and heaving as if the Channel had become the Atlantic, and it was precisely the right time: the tide was coming in fast, and it was reached the places which I most enjoyed watching. So even though I soon realized that I wanted to go to the toilet, I stood there and stood there, walking up and down the beach, and then as the waves covered the sand, up the stairs and along the railings on the promenade. This was so much more exciting than a normal tide and normal waves. In the week or two a year that I managed to see the ocean, there was typically not a lot going on in terms of waves. This was one of the first times that I actually saw the sea on a rampage, and I was in awe.

Were we cute, or what!! This school photo probably comes from Westerleigh Road School in Downend. Based on our faces, I’d guess that it dates from 1959, when Sue was 4 or 5 and I was 6 or 7. The tie was only worn on picture day, I think. Again, mum had knitted the pullover, looking after the pennies.

The waves advanced inexorably. Perhaps that was the thing about the tide coming in that mesmerized me; it was unstoppable even when the sea was calm. With the waves larger and crashing into each other and piling up on each other, that advancing tide inspired awe and fascination, a parade of frothing beasts with nothing to constrain them. The promenade was an L-shaped concrete wall running across the top of the beach and then toward the water. As the tide came in, I first watched the waves rolling in along the part of the wall perpendicular to the sea, and that was exciting with all the splashing and the surf. Then they snuck up to the wall across the top of the beach and finally were slamming into it. The waves did not reach the wall all of the time, and had never before reached so ardently while I was watching. They rammed into it and bounced back and crashed into each other and sprayed over the top of the promenade and churned back out to sea. I wasn’t going anywhere, no way, not until I’d seen all that this marvelous storm had to offer. I’d never seen waves like that. When would I see them again? I just could not leave. I knew that the next morning they’d be gone. It was now or never. The waves churned more and more, and I stood there until I finally realized that the tide was no longer coming in. The waves were still awesome, but the tide was in, as high a tide as I’d ever seen there, at my favorite tide-watching spot, and finally I could leave the sea.

I had been putting off the bathroom for close to two hours, and by this time my hand was stuck down the back of my shorts to hold it all back. Thank goodness it was getting dark! I waddled awkwardly back to the guest house, my stiff posture adopted in an attempt to keep anything from slipping out. My hand remained stuck in there in the same desperate effort to get to a toilet before anything more disgusting happened. I must have looked

ridiculous. I still remember feeling so gross. I don’t remember much of mum and dad’s reaction, except that they helped me wash myself, which probably means that they were understanding about this one-time accident. I do remember my acute shame when I could not get rid of the odor on my hand that night however much I scrubbed.

But I saw the tide come in, and what incredible waves!

In my teens and twenties, I used to look back at this incident with a sort of pride. Staying put on that promenade seemed proof of a capacity on my part, even as an infant, to surmount even the most compelling social constraints! But that interpretation is silly, even pretentious. I was a child. I did dumb things sometimes. Loving the sea made it hard to leave it during my first coastal storm. I’m only writing down the incident because not unsurprisingly it is a strong memory. I guess you could call it a brown letter day!

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 5 Home as a Pressure Cooker

Previous chapter: Chapter 3 Daily Life in a Small World