Another key moment in this young family’s life together in Bristol was attributed by mum to our counting the pennies. She slipped on the stairs while vacuuming one day, and tried not to let the vacuum cleaner fall down the stairs so that it wouldn’t be broken and need to be repaired or replaced. Instead, it dragged her down and she fell awkwardly, slipping a disc in her back and condemning herself to spend months in a plaster jacket, a solid vest made out of plaster of Paris and designed to harshly ensure that her spine did not move and disturb the slipped disc. Those were hard months, but nothing compared to the agony that she suffered for the rest of her life with a bad back that reappeared with depressing regularity.

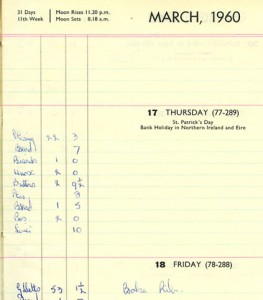

The pennies were still being very carefully counted at home. A 1959 diary entry recites that Moreen and Brian came over to watch “Hancock,” a comedy TV show that was a favorite of theirs. Moreen and Brian came over to our house to watch it because they didn’t rent a TV, and we did. At a cost. Even though dad was advancing steadily up the corporate ladder, and earning as much as any of his peers, we were far from in the clear. Most of the spending fell on mum’s shoulders: she was the one that made ends meet. She had lists of expenses, by the penny, in her 1960 diary.

She miscalculated in the instant when she stumbled on the stairs that day. The vacuum cleaner might have survived the fall better than she did. In any event, if it was broken, one payment would have fixed it. As it was, she was fixing herself, with the family’s help, on and off for years. Dad would help her scratch her trunk with knitting needles during those months that she spent in a plaster jacket, satisfying her terrible itch and unwittingly setting the tone for the future of much of the relationship between mum and each of us. Until I experienced money being tight for myself, after leaving home, I did not understand her miscalculation.

Sue with a patch on her lazy eye. This is dated May 1957, over two years before she had the surgery that was to cure it.

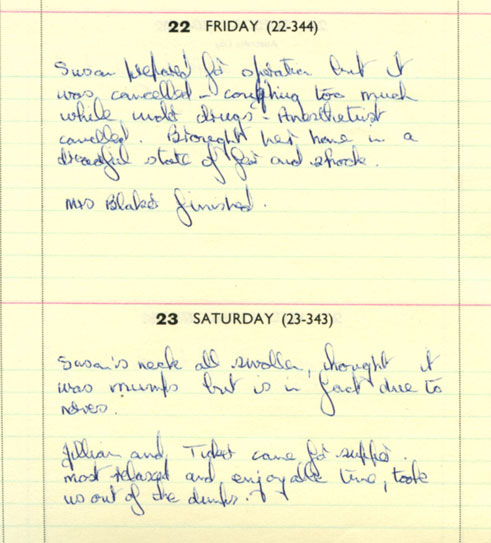

Sue needed surgery at about the same time, still in Bristol. She had a lazy eye, which wandered across her eyeball almost at will, and the doctors said that she needed an operation if she ever wanted to get over it. No guarantees, of course. She was checked into the hospital twice. She could not be operated on the first time because the cough that she developed before going into hospital continued even under anesthetic, and she returned home traumatized. The second time, the surgery was performed, she stayed in hospital for almost a week and returned home traumatized. It was all free: mum’s back and Sue’s lazy eye were all treated almost entirely for free. The only exception was a nominal charge for prescriptions. That was the wonder of the National Health Service. Government could not do away with the sickness, but it did away for a time with the financial penalties that compound health problems.

Mum’s diaries told me about Sue’s two hospital visits. I don’t remember anything but how she looked with an oversized bandage on her eye underneath her National Health metal-rimmed glasses, the sweetest smile under this pathos. One of the class distinctions in post-war England was between attractive frames and glasses and National Health frames and glasses, which again were free or close to it. But they were notoriously unattractive as well as being easy to identify as NHS glasses. The National Health gave Sue her free week in hospital, her free anesthetic and her free eye surgery, and what I remember most is the injustice of her NHS glasses! No wonder that citizens are so easily dissatisfied with their respective States: we see the one remaining small problem when the State has solved all of the big ones. Mum replaced those NHS glasses as promptly as she could.

Mum’s diary from January 1960, showing Sue’s first unsuccessful visit to hospital. The anesthesiologist called off the operation because she was coughing too much, even under the anesthetic.

Sickness and health is one of the key measures of the quality of our lives. The Stocks did pretty well on that scale during my childhood and youth, apart from a few ear infections and flus, although mum probably would not have seen it that way. She focused a great deal on her health, and it did indeed deteriorate while she was still young. As a family, we were lucky until mum and dad got older. Apart from mum’s constant and frequently real ailments, our health did not cause us undue pain or stress.

When mum needed another hospital stay, I forget why, Sue and I were sent from Bristol to Aunty Rose’s. I think that dad dropped us off, but am not sure. Perhaps the hospital stay was something to do with a recurrence of mum’s back, perhaps it was some other ailment. Aunty Rose was lovely, one of my paternal grandmother’s sisters who lived alone in Potter’s Bar with her beautiful face and her miserable life hidden behind the easiest smile in Greater London. Her husband, a shady character according to her side of the family, had walked out on her during the war and never returned. One of her other great assets, and Aunty Rose was just about my favorite aging aunt at the time because of that lovely smile, was that her house was only a couple of hundred yards away from the London and North Eastern Railway main railway line to Newcastle and Scotland.

I already loved trains, and in particular steam locomotives. During an earlier trip to visit her, I actually saw one of the beautifully streamlined Gresley Pacific class steam locomotives that hauled the express trains between London and Scotland. One of their number, “Mallard”, still holds the world speed record for steam locomotives, 125 miles per hour. She attained the record on a long downhill stretch of rail, and blew one of her main bearings either during the record-breaking run or shortly thereafter. But that 1938 record is not seriously contested anywhere in the world. It was night when I saw my first Gresley Pacific, whoomp-whoomp-whoomping its majestic way forward as steamers do at speed, roaring over the road next to Potter’s Bar station, lit up by the streetlights and the platform lights and belching out steam from its funnel and smoke from its driving wheels. You did not have to teach me in later years that engineering was wonderful and brought the world great things; I saw it when I was a small boy and it was roaring along at 80 miles an hour over a bridge across a street in a London suburb.

Sue and I with Betty and Sylvia Ives, Rose’s daughters, presumably in Potter’s Bar. Circa 1958. I was about five and Sue about three.

During this later hospital-induced visit, I managed to ignore the trains’ proximity, which as a train lover was a clear move against my own better interests. Rather than seeing the trains, Sue and I frantically and bizarrely collected sackfuls of acorns in the local park. I don’t remember how it started, or why. We spent hours walking around under the oak trees, hunched over, scooping up acorns by the handful and filling up sacks with them. Where did we get the sacks? No idea. Perhaps from Aunty Rose. Perhaps we found them in the park or on the street. Perhaps the find led us to collect the acorns. But once the sacks were filled and we took them back to Rose’s, I started crying for my parents and just would not stop. I did not want to see the trains because then I would have had less reason to cry. I knew that I was in some sense forcing the tears.

It was really very naughty to Aunty Rose, who had the easy charm and good nature of all the Burrells, her many brothers and sisters. But cry and cry I did until dad was called in Bristol and agreed to change his plans and drive a hundred miles to collect us, and this before there were motorways, to take us back to Bristol before mum came out of hospital. I don’t remember if he took the acorns back with us in the car. I do remember that by forcing my own tears I could push adults toward doing what I wanted. This time at least, they did. At the same time, I felt stupid for missing one of my rare chances to see Gresley Pacifics, guilty for bothering dad when deep down I didn’t really need him, and pleased with myself because he came to take us home.

Perhaps it was our regular moves, the absence of a continuing community outside the home, but we were becoming very close as a nuclear family, unhealthily close. Not being able to put up with staying, with Sue, with one of my favorite relatives, with a chance to see extraordinary steam locomotives, gives some indication that at least from my point of view we had become too close and too dependent on each other.

Clifton Downs during a Sunday walk in 1961, some time after Jackie and Roy Hunt’s wedding (photo below). Mum remembered that the suit I’m wearing, my first, was bought for their wedding.

We developed a ritual over these years. Mum and dad kissed us goodnight in their almost stereotypical manners, a soft and drawn-out hug and sweet nothings from mum, and a brief prickly peck on the cheek from dad, and then the ritual. As she started down stairs mum yelled “goodnight,” and Sue and I wished her a good night too. Then she shouted “sleep tight,” and we shouted it back to her; she shouted “see you in the morning” and we repeated that too; and with all three of us warmed up, she launched into “and I love you, love you, love you,” and we all did, and we shouted it back full throttle. A very comforting little ritual, for all of us, I suspect. It continued almost until I left home, through years where as a male adolescent I would have died before I admitted it outside the home, but it continued. The only variation in those later years was that after a particularly bitter fight with a parent, I would change the last response to “and I hate you, hate you, hate you.” That got the message across!

Family intimacy of a sort did take a small step backward at bath time. Bath time was Sunday evening, when mum, then Sue and I, and then dad, would use the same bath water in succession. What always impressed me at that age was how much dirtier the tub was after dad was finished than after the rest of us had finished. All three of us barely dirtied the water, it seemed to me. But dad had an altogether more visible effect. I was fascinated by the floating grey scum around the rim of the tub. Looking back from 2006, when my family must take 15 to 25 showers a week, with certain of us unable to take a shower in less than 30 minutes, what compelled mum and dad to limit water consumption in that way is simply inaccessible to me. But it must have been something to do with looking after the pennies, probably to reduce the cost of heating water.

Naturally enough, during one of our shared baths, Sue and I explored our differences: we were maybe six and four or seven and five. I don’t remember what we explored, but I do remember the laughter, mum’s as much as our own, and that Sue and I started taking our baths individually, with her first, not long after. Nothing like a little messing about to get to the parents!

20A Skelcher Road, Shirley. It’s out of focus, but dad’s new company car, the Anglia, is in the driveway and mum is in the upstairs window. We moved there in early 1961.

Bristol also marked the start of independence for me, with my being allowed to walk the Paignton sea-front alone for hours a typical example. Naturally enough, that independence became the beginning of a great unending exploration. My first bicycle was the key in Bristol. Dad made me clean the bike regularly and helped me learn how to oil it. But I was allowed to ride alone at a young age in ways that would horrify parents in the 21st century. There were fewer and slower cars on the roads, which themselves were slower than fifty years later, and the dangers were simply not perceived. I never wore a bicycle helmet until my twenties, and would not have recognized one. Consequently, until driving age, the bike of the moment was my key outlet, my nuclear family safety valve, as well as my key to living what you need to live to leave home.

Mum presenting Sue to the bride at Jackie and Roy Hunt’s wedding in Bristol on April 1, 1961. Check out her gloves! Roy played hockey with dad at Henleaze, and Jackie was the first woman I ever realized was beautiful.

I once plucked up my courage enough, and polished my sense of direction enough, to ride for miles over to Filton, to dad’s office with the forerunner of British Aerospace, on the little bike of the time. The bike cannot have had had wheels larger than 16 inches. Don’t ask me how I found his office! I have no idea. I do remember that the roads looked very different than from a car, and that I was very worried most of the way that I was missing a turn or had become disoriented. For a young would-be explorer, this was a peak experience. I don’t remember how old I was, but we left Bristol soon after I turned eight.

I was stopped at the factory gates by a security guard. He would not let me in but he did call dad in his office to come and see me. Dad came to the gate looking rather embarrassed, sheepish almost, and sent me back home on my bike. Being made to feel unwelcome was a bit of a let-down, I must admit. I was so proud of having found his office, and had hoped that he would drive me back home with the bike in the boot of his car. That way, I would not have to bicycle again under the high-tension wires which had been my biggest fear on the ride out. What if one of the wires fell and frazzled me in a flash? What if the strange vibrating-humming sound that they made could do harm? As it was, I again pedaled like mad when I reached the wires to get out from under them in a hurry. I’m tempted to make something of being sent away like that by dad, but don’t believe that it hurt in any real way. The adventure was as complete whatever the welcome at the destination. It was dad’s loss not to be able to enjoy it as I did. He missed out on a lot because of his English reserve, perhaps also because of the era’s requirements of a junior professional position.

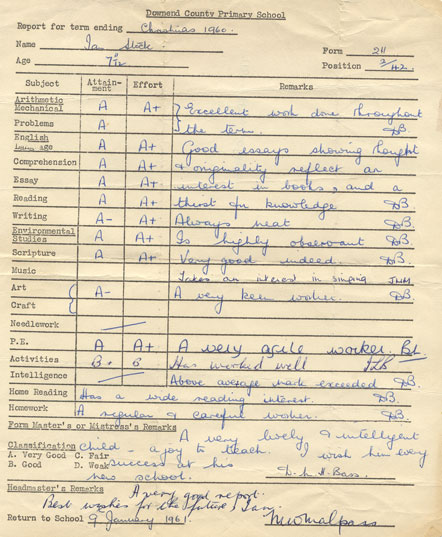

My last grade report from Westerleigh Road School, for the autumn term 1960, which ended just before Christmas. Very flattering, but check out the Music line!

I felt that he let me down upon another occasion in Bristol. The boy down the street and I had squabbled about something, and he had hit me on the forehead with a garden rake, the pointed metal part. I still have the scar. Mum was horrified: an inch away and it could have lost me an eye. Dad was sent down the street to settle things with the neighbors. He didn’t do anything! The other boy’s father was apologetic and said that his son would be punished, and dad thanked him. Now that was a let-down. I get a rake stuck in the forehead and all he can muster up is a polite visit.

I didn’t know why it was so important for me to explore outside the house, as I did constantly, but it was an imperative. We were so close at home, and so locked in to each other, that home was a pressure cooker. I didn’t think about escaping; I thought about where I was going, and how I absolutely had to go there, if it was only the street corner. But I was escaping. I bounced off walls in the house; I bounced off walls and crashed into mum, mostly, or occasionally dad. I was a human pinball, ricocheting as if from spring-loaded cushion to spring-loaded cushion, bouncing faster and faster until I bounced right out of the door.

Aunty Nana and Uncle Frank during a visit to Skelcher Road in 1963 or ’64. They are standing in the back garden, and the postwar buildings of Haslucks Green County Primary School are in the background. Aunty Nana was a friend of Grandma Smith, and helped Grandpa look after mum after Grandma died in 1937 aged 47. Mum had yet to turn 11. That was young to lose your mother.

Mum and dad never fought it. They let me go. I suspect that they had to let me go. If they hadn’t, I would have gone anyway and it would have been worse. The explanation was the family pressure cooker, all that love and all those feelings, corrupted on some level from day one and flowing backwards and forwards among the four of us, bouncing off the walls. When I wasn’t out and about, letting off steam, I was being difficult for mum and dad, doing my part of being the family pressure cooker, although of course I did not see it that way at the time. For instance, I was a very picky and finicky eater, especially on the road. Searching for a café on our Sunday afternoon trips exploring the countryside, or even on our way to or from Paignton, was a constant problem because I essentially refused until age ten or eleven to eat anything out but beans on toast. Beans on toast? Madeleines, they are not! First, they are cooked and eaten hot and sticky. They have nothing that is sensually delicate. They are comprised, no surprise here, of heated vegetarian baked beans served on buttered toast. The beans are rich in tomato ketchup, or if they weren’t at a café I could add some. That was probably the secret of the meal’s success. But the taste of beans on toast was thicker than ketchup, which has its own spicy delicacy, and their gummy texture rolling around in my mouth had more to do with a lump of grease than anything worth melting into raptures about.

The immortal beans on toast. This was taken in 2008, but the meal has evolved little over the years. One of the TV ads from the 1960s featured the addictive jingle: “A million housewives every day pick up a tin of beans and say: ‘Beanz Meanz Heinz!'”

I loved beans on toast to the exclusion of most everything else, at least out of the house, for most of my childhood years. It is a meal still common in the UK. Perhaps they were of wartime origin, because of their simplicity and low cost. They are still served most often in cafes frequented by lorry drivers called “transport caffs” (the e in café is silent). But the importance of beans on toast for us then was the constant hassle that we all had to go through to suit everybody’s different and conflicting tastes on the road, a hassle that I made a significant contribution to with my insistence on eating that particular meal at almost all times.

Feeding me at home was no easier. After the little accident with my front teeth on the stairs, chewing became more difficult, and I could not eat meat. At least, that was how we all phrased the problem, ignoring that it was only the cutting teeth that had gone. The chewing teeth remained, and if meat was cut into small pieces, there was no apparent reason for my not being able to eat it. Mum tried that, more than once, but I never would eat meat until my teenage years. I think that I did make a good faith effort to eat it, and have memories of nausea prompted by unending chewing on stringy beef. It became a flavorless string that I would spit out for fear of it sticking in my throat if I tried to swallow. My refusals to eat or difficulty eating forced mum to put a lot of effort into adapting her menus to suit her budget and my excessive pickiness. My favorites were casseroled liver and onions, with the onions spread on slices of bread, and casseroled cod in Heinz tomato soup, with, you guessed it, the soup spread on slices of bread. Bread has always played a significant role in my culinary life, as has its texture when soup or rich gravy soaks it through: what is the word for that rich and creamy feeling?

My front teeth came back! Protruding a little, it is true, because I sucked my thumb until the orthodontist forced me to stop at around age 11. This photo was taken at Haslucks Green during the “Christmas Term,” according to its cardboard frame. 1962 or ’63, I think.

Chocolate. The only thing that I ate and ate without limit or restraint was chocolate. Not a day went by when I did not crave chocolate, and most days I managed to eat a little. Modern knowledge decries permitting children, especially more active children, to eat unlimited sweets. This constitutes an important advance on the state of knowledge when we were little. My only limit on sweets was budgetary, and I worked around it by spending most of my lunch money on sweets when I was out for the day, as I often was on weekends beginning in Birmingham around nine or ten years old. We had deserts every evening after the main course, up to two little cakes until my teenage years, and little chocolate treats when Sue and I were out with mum, dad, or mum and dad. In short, there was always a little chocolate in one form or another.

The sages who administered and taught at Haslucks Green County Primary School, my first school in Birmingham, took us on a rare school trip to visit the Cadbury chocolate factory in Bourneville, part of Birmingham. This was enlightened education! We trooped around the factory like a dozen litters of excited puppies, shirts coming out of our short pants, skipping and bouncing and snaking our way through the maze of conveyor belts and shiny chocolate making equipment, trying not to touch everything in sight. The whole place was rich with the smell of chocolate, which was surprisingly heavy and dense until we accustomed ourselves to it. They let us eat as many chocolates as we wanted off the conveyor belts as they rolled by. I kept eating until I was forcing them down and worrying that my stomach was going to throw it all back up. What an unrequited treat! Then they gave us free samples of chocolate bars and cream or nut chocolates on the way out. That was my first contact with enlightened marketing. I have been a loyal Cadbury’s customer ever since.

My hyperactivity, my constant demands on mum about food, because being a picky eater is in large part a way to make demands on she who is feeding you, my sugar-ridden diet, mum’s and dad’s budgetary constraints and respective affairs, not forgetting Sue’s and mum’s ailments, all combined to create a maelstrom out of the early years of this nuclear family.

On a day trip to Windsor from Shirley in 1961. We probably stopped in to see Grandma Stock too. She lived in Southall, which was not far away from Windsor by car, a bit further in terms of class. That parrot really hurt!

I was constantly in trouble at home, and almost as constantly convinced that it wasn’t my fault. Sue could not be “excited.” That was the medical advice reiterated ad infinitum at home. If I had been able to think in that way in those days, I would have wanted to shoot that doctor. He asked for the impossible, and set up an emotional dynamic that I could only lose. There were just the two of us, there would only ever be just the two of us, and so whenever either of us did something wrong, or whenever either of us annoyed mum, and mum was easily annoyed, I was the only one who caught it. Who knows how much trouble Sue and I respectively caused? Boys will be boys, and my share may well have been the lion’s share. But what I was inexorably and unbearably and incessantly punished for and yelled at about was everything, because Sue could not be excited and yelling at her risked exciting her. It was only in much later years that I realized that, as much as Sue profited from this principle in the way that children do by doing her share to see to it that I was always the one who was told off, it also made her feel in a way impotent. It was as if whatever she did was really my doing. It was as if she did nothing that was worth a parental response.

By the time I was nine or ten years old, I had become quietly and discretely, but oh so fervently, convinced that my parents were weaving complicated webs of intrigue to ensure that I would get into trouble again and again. I would repeat to myself in a quest for comfort and relief from the incessant reproaches that they were “planning” my misbehavior, they were “planning” against me. It was incessant. Day after day, evening after evening, they yelled and yelled at me. Day after day, evening after evening, I saw it

more and more as their fault, their creation. Can a child really accept responsibility for a continually expanding range of wrongs that his parents identify and then berate him for, shout at him about and punish him for? I don’t think so. Maybe if there are fewer scenes about fewer wrongs, that small person with a big child’s heart could assimilate them and learn from them. But excessive yelling and screaming gets the parents nowhere, because the child cannot surmount the cognitive dissonance that it forms between his neediness and their retribution. Mum and dad knew that the excessive yelling was an issue, prompting their own rule that they both could not yell at me together on the same issue, which they did generally stick to. But that rule did not stop the constant yelling, just occasionally turned it into them yelling at each other about me, which was not a lot better from where I sat. I couldn’t see any way out of it other than blaming them. I was just little me: a normal boy, a nice boy. I couldn’t possibly be responsible for all that they were putting on my fragile shoulders. It was them. It had to be them.

Mum remembered that she bought this dress in Birmingham. She and dad attended regular British Bakeries Midland Region functions, and this must have been one of them, perhaps a dinner for Harding’s or Wimbush’s bakery, or perhaps one thrown by Alan Law, General Secretary of the local branch of the Transport and General Workers Union.

I focused intensely on their planning and the trouble they managed to get me into, and for a while developed a bizarre belief which may have had something to do with it. I was the secretly adopted son of the Queen. I had theories about why she had cause to have one of her sons secretly adopted. The inconsistency between this belief and the stories of my birth, which I simultaneously held dear, did perplex me, but I found ways around that. It was not for long, but for a short while this secret adoption gave me comfort. One day she would take me away, or if she could not take me away for the same reason that she had had me secretly adopted, she would see to it that I was properly taken care of. I seriously needed a refuge!

I once blurted out to both my parents, in the middle of yet another painful session of being yelled at and told off, that I knew that they were making plans to get me into trouble. That session quieted down in a hurry! Maybe they were thinking, “a textbook case”, as my Nevada City friend Ron Snyder commented when I recounted the “planning” to him ten years later. Maybe they realized all of a sudden how much they had developed the habit of telling me off.

Or maybe they were thinking that it was time to put the fish in the oven.

Reproaches and berating were not the sum of their parental actions, but when they occurred for years I was almost their sole object, and it drove me a little bit crazy.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 6 Success at School

Previous chapter: Chapter 4 The English Riviera