(From “Homeward Bound,” written by Paul Simon, and performed by Simon and Garfunkel)

They dropped me off in early January 1966 at Kineton, the annex to the boarding house for younger boys. I had just turned thirteen, and felt very much a small boy in the driveway that day, watching them drive away and trying to hide my feelings. I was old enough to know that I shouldn’t be seen to cry. I didn’t look thirteen, or feel it when they left me alone. I felt so small. I felt so alone, so empty, so abandoned. The sadness throbbed and waned: I ached continually for months. My bright and successful new world as a scholarship boy became something completely different, something that began with an ache that was too strong now, too much to overcome. The emptiness hit me over the first few days at Kineton, as the boarding routine sank in, as the finality of what we had done so casually hit me.

I needed my family so badly. Time after time, I snuck away from the other boys to cry my heart out in private, looking out of the window on to the greyness outside, wishing that mum and dad would appear out of nowhere and take me home, wondering why it hurt so bad. The other boys must have known that I was spending much of my time in private corners of Kineton crying, but none of them referred to it. It was something I would need to get through, something that each of them had already gotten through, more or less, a stage. We all played our parts in the script.

In my summer uniform, complete with boater, in the driveway at Kineton. I can’t figure out when this was taken, because I started at Kineton in January and would have been wearing a winter uniform then. Maybe it was when I was collected in July to spend the summer at our new home in Marlow. I lived in Kineton, the junior boarding house, for seven long months.

I worried mum and dad by calling periodically, but when they called Mr. McGowan, the Headmaster whom we all believed in, to ask what to do about their occasionally hysterical thirteen year-old boy, he told them that I would get over it. I needed two years to derive real benefit out of boarding, he said. It was not the Stock way to quit: I already knew that somehow. Even as I begged mum over the phone at first to bring me home, I knew that I couldn’t go.

That was the biggest part of those early aches. We had made a dumb mistake, which was not so bad, but some sort of misplaced sense of duty or honor, or less nobly some misplaced advice, compelled us all to stick with it and make it so much worse.

In my own letters, I tried to act the part of the boy adjusting to this bizarre and perverse separation, and mum and dad in theirs tried to act the part of the supportive parents who found it completely normal to be abruptly and prematurely separated from their much-loved offspring. All the boys in Kineton played their roles of little men whose parents and family were there, of course, in the background but not strictly necessary. We were asked to grow up overnight and in my case too soon.

There were boys there, Simon Billing was one, who had been asked to grow up at age 8, who were sent to board at the earliest age that the school accepted boarders. At least my beginning to board had a coherent rationale, based on success at the school and dad’s promotion. What was the rationale of those parents who washed their hands of their own sons at age 8? To make men of them?

The grief continued. Most was the real trauma of separation from my family, a family that I had become particularly dependent on because of our regular moves away from every community around us. We four had been the only consistent community in my short life. The tears continued. I was still crying, as regularly as but more discretely than at the beginning, to the point at times of barely being able to breathe.

Two songs that played on the radio during 1966 were the year’s theme music: Simon and Garfunkel singing “Homeward Bound,” and the Beach Boys singing “Sloop John B.” Both were playing on the radio during the first half of the year, homesickness on record giving me the words that I needed to express my feelings. The Beach Boys: “. . . hoist up the John B’s sail, see how the mainsail sets, call for the Captain ashore, let me go home, let me go home. I wanna go home, let me go home, why don’t you let me go home . . . ?” (From “Sloop John B,” written by Brian Wilson, and performed by the Beach Boys). Simon and Garfunkel: “All my words come back to me in shades of mediocrity; like emptiness and harmony I need someone to comfort me. Homeward bound, I wish I was homeward bound.” From “Homeward Bound,” written by Paul Simon, and performed by Simon and Garfunkel). Nothing complicated or subtle: just the raw and insistent feelings of a homesick little boy.

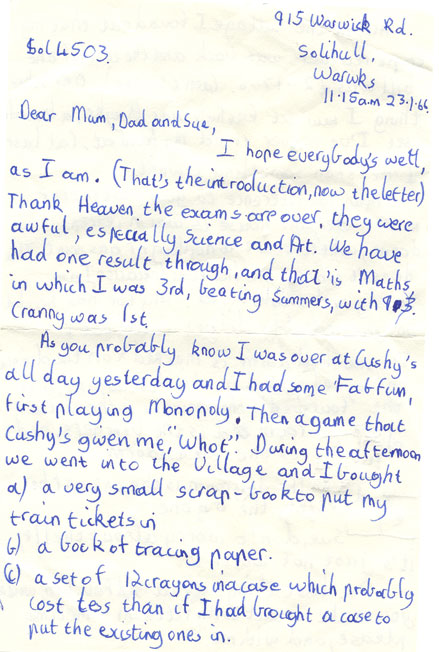

The first page of an early letter home, about two weeks into Kineton. As ever, I was thrilled about doing well in the exams. Ian Summers went on to become Professor of Physics. Cranny teaches maths at a public school. I am tempted to attribute this discrepancy in their achievement to Cranny’s boarding. Ian was always a day boy. Mum had carefully stored all of these letters, and I found them clearing out 18 South View Road after she died in 1996.

Boarding changed all the rules of home and most of the rules of the school for a day-boy, even some that it made no sense to change. Boys were only allowed out of the school grounds two afternoons a week from four until six, and then only to walk into the town center a few hundred yards away. That made some sort of sense in terms of protecting us, at least.

But it meant that my safety valves of evening tours around the neighborhood to bike or play football were gone. All boys need safety valves, room to breathe, to explore. Not only that, but concentrating on the work in the evening was also much more difficult. Missing my family discouraged me, and other boarders did not work very hard and did not want anyone to work very hard. None of them were in my class, and only a few among them were in the top stream of other years.

Rather than applying myself whole-heartedly to the challenges posed by my schoolwork and deriving reassurance from them, I was undermined by the non-conformism that doing schoolwork represented among the boarders. That cannot have made any sense from the school’s point of view, institutionally discouraging its own pupils from studying.

Most importantly, nothing replaced the easy intimacy that we had at home, and nothing replaced the depth and constancy of our communication. The boys at Kineton were neither as kind nor as smart as the boys in my class, but because I was one of the oldest in the house, that difference was not too significant. The other boys in Kineton had no power over me. I doubt that they were poorer talkers than the other boys whom I had known in the past. Rather, mum and dad weren’t there, and neither John Gregory nor Guy Moody, the two older boys who acted as our house mothers, nor the resident adults had much of an incentive to replace them. “. . . let me go home, let me go home. I wanna go home, let me go home, why don’t you let me go home . . . ? “ (From “Sloop John B,” written by Brian Wilson, and performed by the Beach Boys).

The school was supposed to make men of us, after all, and a teary-eyed boy who needed desperately to talk but was struggling to figure out what about hit all the wrong buttons, however kind the older boys were, and they sometimes were kind in a confused sort of way. Underlying their attempts at times to help was an unstated but obvious truth for them: they had overcome homesickness in their turn, and I would need to overcome it in mine.

I don’t remember much of what happened between us younger boys, but do remember one attempt at meaningful communication that was a little troubling. The boy concerned, a quieter boy who wore glasses and was not at all mean, buttonholed me one evening and uncharacteristically ignored my polite attempts to cut short his odd monologue. Normally a deferential boy responsive to others, he was clearly profoundly moved by what he had to say and needed to share it with someone. I was his pick for sharing. He began by insisting on telling me in a secretive and urgent way all about how babies were made. “Do you know how it’s done, Stocky, how a man and a woman make a baby?”

I did not, and did not particularly care to at that point, but this did not deter him. He was involved in a momentary conspiracy with me, and whether or not I conspired with him was irrelevant. Pressing discoveries were preoccupying him a year or two before they would interest me. “You know how your thing gets big, well babies are made by the man sticking his thing into hers when it gets big.” This boggled my mind, and I tried unsuccessfully to imagine it. An odd discussion, and although it was not entirely uninteresting, I had had enough. As I started to move away, he grabbed my arm, still involved in this strange one-sided conspiracy, and went on to describe how at night alone when he played with his after it got big, and if he played with it long enough, he could get creamy white stuff coming out of it, and that was sperm. With no idea yet of these things, I was simply repulsed by this last revelation and escaped as fast as I could.

Sue and Cranny at Bekonscot, a model village in Beaconsfield, near Marlow, during his 1966 visit. Didn’t Sue have a lovely smile!

Summer brought a respite. They let me go home for six weeks, and exactly twenty years to the day before my oldest son Nick was born in Manhattan, the English football team won the World Cup for the first time in their history on their own turf at Wembley in London. 1966 would not be all bad.

The family now lived in Marlow, where they had moved in February. It wasn’t home for me yet, but it was very reassuring to be back with the family for a while. The high spot of the summer was Cranny’s visit. Cranny was Richard Cranston, a friend from Solihull School who had impressed me by being both extrovert for a clever boy, as I was, and being able to make radios in matchboxes, which I didn’t even dare to try.

We were pretty good friends already, and I’d visited his home in Sutton on the other side of Birmingham when still a day boy at the school. He had taken me across the road from his house on to the golf course for my first and only golf lesson, with him doing the teaching. After the summer he was going to become a boarder, and mum and I hoped that he would be the friend there that I needed in the boarding house to help me adjust. Friends who were “day boys” didn’t seem to matter much or help at all. Don’t know why. Cranny spent about a week down in Marlow staying with us.

He had an enjoyable visit, but to be honest it was more with my sister than with me. He was if anything overdeveloped for his age: I had seen him naked in the dressing room. My sister was flourishing in my absence: she could finally spread her wings without an older brother around to cramp her style, and she had both parents practically to herself. I honestly didn’t understand what he saw in Sue, what boys saw in girls, although I had noticed that Sue at almost twelve was beginning to develop longer legs to go with her long blond hair. I didn’t mind Cranny’s interest in her. Perhaps that would help him remain interested in me during the next school year. I so wanted a friend in the boarding house. How I got one didn’t matter. We explored the area, most of the time as a threesome, and after he left we went on our family summer holiday, on a train to Scotland again. I was feeling almost normal again by the time I went back to Solihull.

Poor quality here, taken out of the 1966 photo of the entire School House. The boarders were all in School House, one of the competitive houses to which pupils belonged. From left to right: Simon Billing, John Moore, Clive Duckett and me.

It didn’t last. My fourteenth year seemed to go on a long time. After the summer I moved to the School House, the main boarding house with boys up to the age of eighteen. I was in a dorm of ten or twelve boys, most of whom were a year older and a few years harder than me. Communication between boys was getting worse from my point of view as we grew older. The urge to be cool must characterize boys uniformly across social groupings, even across generations. In the boarding house, this urge was magnified, reinforced by the pressure cooker of our collective lock-up. It was a constant and unremitting pressure.

It was all about being cool, and I frankly wasn’t cool enough. Take the dirty jokes in the dorm, the regular sessions of competitive dirty jokes after lights out. I have always remembered one joke that won the competition one night: I think that it was Simon Billing’s. Two airmen were marooned in a storm in a land peopled by cannibals. They were captured and separated. The cannibal Chief showed the co-pilot the enormous cauldron steaming on the fire, big enough to hold a man, and told him that he needed to bring back a thousand grapes within the hour if he wanted to avoid being baked on the fire. Off he ran and duly returned within the hour with over a thousand grapes. The Chief told him to shove them all up his butt without giggling or laughing if he wanted to avoid the fire. The co-pilot got to the nine hundred and ninety-ninth grape when he burst out laughing uncontrollably. The Chief was perplexed. “Why did you laugh?” he asked, “you were almost there, only one grape to go!” The co-pilot snickered again: “I saw the pilot coming back with two bunches of coconuts.”

I giggled at that joke at the time, one of the few that actually amused me, and still find it funny, but for some reason could not build on that kind of crack in the wall of my differences from the other boys. Even when I could have shared with them by putting in a little effort, I did not do so and continued in my misery with a kind of single-minded determination.

Sue and Cranny playing ping pong one evening on our dining room table.

In part, then, I was doing it to myself. At most times in my young life I was able to be cool enough, to go along with the coolness rules of each particular group of boys that I belonged to. Maybe I wouldn’t go all the way, but I could have at least worked at joining in the coolness of the boarding group with the dirty jokes. Instead, I concentrated on how much I hated them and the boys who told them. I was going too far, like my mum falling down the stairs in Bristol holding the vacuum cleaner so that it would not break. My pattern was the same as hers, the same as my own when I started crying when Sue and I were staying with Aunty Rose, even though she was such a sweetheart. Once I got into it, I was not going to get out of it until I got what I wanted, a kind of self-destructive determination.

But mostly the social world of boarding was doing it to me. The older boys’ whole obsession with dirty jokes, with sex and girls and tits and shit and all that, was very distressing for immature little me. It was hard to be cool when, if I did hear a dirty joke, I was sufficiently put off by the subject matter to find it difficult to remember. Not having reached puberty had its side effects. I did not understand their appeal, and felt different and smaller when I couldn’t seem to join in. I may have done it to myself not to join in, but being unable to made me feel different again, and smaller.

In later years I have always had great empathy with outsiders, those whose beliefs or skin color or predilections separate them from the larger community. Inability to be cool in a particular group is one of the least virulent of these separations, but it conveys something of their quality. That was what boarding was all about for me, especially after moving into the principal boarding house: separation from the larger community. As all outsiders know, however stronger or better they may believe themselves, being an outsider makes you feel small, and not being able to move from the outside to the inside makes you feel smaller even as you profess not to want to anyway. I was somehow outside a boys’ world built on and around the changes that puberty would bring. That was the key difference from Kineton. The ambience there was not as infected by these changes. The older boys did not live in Kineton.

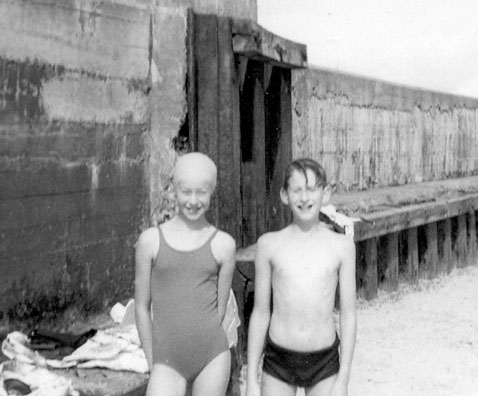

Sue and skinny me on the beach in Nairn during the family’s 1966 summer holiday. I was 13 and Sue 11. I ate very little as a boarder.

It wasn’t simply the older boys establishing and enforcing what was cool based on the preoccupations of puberty. The older boys in my dorm competed to put down the younger, unless the younger tried to act as tough and hard as them. I wasn’t up to that. A couple of times, they had us run down the lane between the beds getting flicked by towels that they wielded with great skill. Light entertainment for would-be sadists.

Even the teachers could inadvertently traumatize. One evening, Mr. H. R. Rickman, known as Harry Crow because of his predatory profile, made his nightly visit to the dorm to wish us goodnight and added an unusual postscript. Before turning out the lights, he gave us the terrible admonition that we should pray for the children of Aberfan. Over a hundred Welsh schoolchildren, he elaborated, had been buried alive in their school that day and killed by a slag heap that had collapsed on the school in a rainstorm.

In the dark I thought about it. I knew that a slag heap was a man-made mountain of black dirt, the leftovers from coal mining when the coal was taken out of the ground. Slag heaps were always very steep sided so that the maximum waste could be stored on the least land. It was a sensible calculation, but on this occasion in hours of heavy rain the sensible calculation had gone horribly wrong. I could not sleep thinking about those tons of black dirt crashing through the schoolhouse roof in the rain and forcing their way into those little warm mouths. Did they choke on the dirt or drown in the flow of rainwater? How did it feel to suffocate? Harry Crow must have meant well, but how can such obvious sadism be inadvertent? “Let me go home, I wanna go home, Let me go home, Why don’t you let me go home, Hoist up the John B’s sail, I feel so broke up I wanna go home, Let me go home. “ (From “Sloop John B”).

My high hopes for Cranny were soon dashed. The reason that he was boarding now was that his mum had suddenly run off with another man, abandoning him and his dad. Not knowing quite how to cope, his dad sent him off to boarding school. It wasn’t entirely surprising that he hardened quickly and fitted in with the other boys much better than me. I still had my family, as he had seen very clearly just that summer, even if they were a hundred miles away. He did not. It was over for him on some level for the rest of his life, and he knew it already. He was probably hardened within a few months of his mum’s leaving.

I have a photo that I stole from the corridor in the School years after I left. It is of the boarding house’s football team in 1970. Cranny is in it with the boys our age and a little older that he became friends with when he started boarding in 1966 and dropped me. His face shares all of the hardness of the other boys’ faces. He was already well on his way that winter to the hardness etched so proudly in the photo, and my best laid plans for him had not worked. I felt a more bitter solitude. Years later I had a better understanding of what had happened to Cranny when his mum abandoned him as well as his dad for some unknown man. But not during that miserable winter term at Solihull.

Of course, family life followed its normal course outside the school. Dave Warrington, Aunty Vi’s older son, married Pam, both to Sue’s right. In the middle here, she was a bridesmaid. Peter Whitton, “Pip,” Margaret and Ron’s older son, is on the right. I was at school, and unable to leave the boarding house to attend.

Bruce MacGowan did his part to try to help. I was made Head Boy’s fag, which despite the language was sort of an honor. All the younger boys were fags: it was another part of the socialization process. A fag did menial work or chores for an older boy, under his control and subject to his substantial discretion. He could not be abusive, but if he wanted to act as a kind of regimental sergeant major he could. If the older boy wanted his fag to scrub his floor until it shone, he theoretically could, for example. That would likely not be considered abusive.

I made the tea for Roger “Bart” Gribble, all-round athlete and the school’s head boy that year. He was kind to me, and had me do very little to fulfill my functions as his fag. Apart from making his tea, all I remember doing was polishing his shoes. He never took advantage of his position to badger me or criticize me unfairly. By picking me for Bart Gribble, the Headmaster was assuring that at least this subset of the school’s social system did me no harm.

It was not enough, and the bitterness started to fester as that winter term progressed. I can’t remember what went wrong at rugby. Perhaps I was just late growing up and building out. I sure was skinny. Dad wondered later if the trauma of being a boarder had not arrested my physical development. In any event, I didn’t eat enough, and was no longer competing for a place on the school team. When this year’s cross-country run came around, I was mortified to finish third or fourth. What was going wrong? I had won it before. The answer was easy, if I could have thought it through or been advised by the PE teacher. The winners had started regular training for the race. I could have recognized or been told that I needed to start training myself, to recover my earlier advantage. But in my growing bitterness, I blamed boarding and the misery it had caused. As a result, I didn’t ask why no-one had advised me to train. I would have if I’d been told.

The same thing happened in that year’s public speaking competition. Not only did I not win it, I failed to qualify for the finals. Again I felt terrible, explaining it to myself as yet another consequence of boarding. The explanation was more congruent with the reality on this occasion, because the homesickness and misery had already closed me emotionally to some degree, and the best public speaking involved a meticulous emotional openness. But in my bitterness I again thought only of what I had lost and not about how to rectify it. For instance, Bogbrush no longer had me reading aloud in class all the time, because he no longer taught me English. I could perhaps have recovered a lot of the earlier ability with a little practice, but did not even think of doing so.

This is the last letter from boarding school that mum kept, dated two months after I started there. Things were starting to read more normally: “rotten swiz”?! Swatty was Mr. P. R. Ansell, who taught us maths.

Studying was viewed as something to be avoided by the older boys. They did as little of it as they could, I think so as to be cool. I would love to know how Cranny evolved. Before boarding, he was very bright. Was he still when he had hardened before he left Solihull at eighteen or nineteen?

I dreaded that heavy feeling of not conforming whenever I studied. Study hall, the required period of an hour and a half each evening when we were all supposed to do our homework, seemed to have been designed to unlearn good study habits. We were all shut in together, the socialized and the being socialized. Studying was very difficult while all around were taking pride in how little they could do and how much they could fool around during study hall. I did study a fair bit, enough to come close to top in my class still a few times.

But if I had been told to study in a solitary place, if each of us were told to study in a solitary place, the deterrent effects of the older boys, of the socialization process, would have been much reduced. But no, I was a non-conformist not just because I was a bit too soft, but also because I was a nerdy swatter who actually liked to study. Being a non-conformist can sound romantic or courageous, but as a child among contemptuous older boys it feels the opposite.

It was beginning to seem as if every way I turned as a boarder I felt smaller. Dougal Mackay was one of the nicer boys of my age who had moved across from Kineton with me. His father was the Chairman of a well-known public company, in telephone equipment, if I remember correctly. Dougal had been adopted, although I couldn’t fathom why his parents adopted him only to send him off to boarding school.

Then there were the amost institutional fights that characterized the boarding house. I remember Cranny having a fight one evening that winter term in our day-room with Simon Billing. He was about our age, smaller than Cranny, but very agile and wiry. He had been one of the only two young boys selected to give the bouquet of flowers to Queen Elizabeth when she visited the school to celebrate its 400th anniversary. In later years, he hastened to explain that honor as being attributable to the number of generations of Billings who had attended the school, and not of course to any merit on his part. In fact, if he remembered correctly, he had detention before Her Majesty arrived.

That was Simon: at 13 already one of the very cool boys in the boarding house. He and Cranny were really going at it, sliding across the linoleum on their backs or rolling over into the furniture, both of them turning red with the effort. I watched and noticed that, much as I didn’t like what they were doing and sought to avoid doing it myself, I felt excluded. Somehow they had created an intimacy out of that fight, although it took a while to surface in normal life. They were learning the right language together, and later became friends, I think. Simon’s younger brother is with Cranny in the photo of the hard boys that I stole years later. Deriving intimacy out of a kind of enforced toughness and proud hardness was what boarding seemed to be designed to accomplish.

Oddly enough, what was accomplished by boarding was accomplished by the older boys rather than the adults, although the latter remained to my mind aware of what was happening and thus the accomplices of the older boys. At one point, the older boys’ desired that Dougal and I fight: another example of boarding school socialization, another way to help us to get harder whether we wanted to or not. No boy wants to be afraid to fight, or to be seen to be afraid to fight. Each of the older boys had fought in his turn at one time or another under that pressure.

So with a little help from them, Dougal and I would fight and get over being the wimps that we were or that they perceived us to be. With Dougal, I got lucky. Neither he nor I wanted to fight, and especially not because these creeps wanted us to. We weren’t close enough to phrase it that way, but when we were escorted out to the edge of the playing fields one evening by one of the older boys to get the job done, we circled each other for a while with the adrenaline pumping as they had intended, but never did let ourselves get into the fight that they wanted. It was an unexpected outcome, for us as well as for the older boys. Perhaps I remembered the shame that I had felt in the past when I got angry enough in a fight to win it. Perhaps I literally could not do it without the edge of that anger. Now I can feel proud in retrospect for not letting that pressure force me into a fight that I did not believe in or even into anger of my own. At the time, I was left feeling terribly small, yet again. Was I a coward?

Boarding in England at that time normally involved corporal punishment, which was then an inexorable part of English education. I had been caned once or twice at the school as a day-boy, for small infractions like daring to cut across a grass corner of the quadrangle when rushing between distant classes. Being caned hurt a lot, even when the punishment was only one stroke of the cane.

Dougal and I went exploring one evening, and found a door unlocked in the corridor outside the school’s main assembly hall. The passageway behind it led up a long stairwell. Being boys with our sense of exploration not entirely extinguished yet, we climbed all the way up, and found ourselves above the ceiling of the assembly hall in a kind of attic under the roof. Planks criss-crossed the beams of the roof, but between the beams was only sheetrock or plaster. We tip-toed nervously around, until Dougal managed somehow to let his foot slip off one of the planks and through the ceiling of the assembly hall. The hole was still there, patched of course, thirty years later when I played tourist at the school, which gave me great satisfaction.

The good news at the time was that Dougal did not follow his foot: the ceiling was a good twenty feet above the solid wood floor that would have killed or paralyzed him. The bad news was that we scurried away leaving a heap of plaster on the floor and an incredibly conspicuous hole, a lot bigger than Dougal’s foot, in the ceiling of the assembly hall. We knew that we were in for it.

The “hard boys,” the photo that I found on a wall in the boarding house in the early 70s. I was long gone from the school, and took the photo with me because it was a pictorial record of the hardness on the boy’s faces. After leaving, I wondered if I had imagined it. Here it is etched, deliberately it seems to me, by the boys themselves, part of their pose. Cranny is bottom right.

We confessed when the housemaster asked for a confession from the anonymous malfeasors the next day, and after a suitable period to reinforce our fear of the impending punishment were called one by one to Harry Crow’s office, where the punishment was to be meted out. For some reason which did not feel very bright even then, I had stuffed a washcloth down my pants to help ease the pain. “Bend over,” he said, flexing the cane in his hand. Perhaps he made a comment about the type of cane he was using, and how it was appropriate for some reason for meting out fair punishment or punishment with no risk of lasting harm. They made comments like that before caning, I suppose to demonstrate their inherent humanity or humanism. Then they caned your buttocks with real force and a big swish. It hurt like hell. He gave me three strokes, which indicated a serious wrong, but with mitigating circumstances. In our case, the mitigating circumstance was probably that we confessed rather than that we had not acted maliciously. I tried not to cry, and succeeded, but the tears forced their way out even when the sobs were blocked. Then he asked me to take the washcloth out of my pants, and bent me over again. The second three strokes hurt more, and I was sobbing by the time I stumbled out, trying to figure out whether it hurt more because my buttocks were already swollen and bruised or because he had hit me harder the second time in expressing his annoyance about the washcloth. I wasn’t singing Sloop John B to myself any more. There was no way out.

I had never experienced the emotionally charged position of presenting my buttocks before Solihull, and had experienced it in two ways there, in scrums on the rugby field and while being caned. The former is virile, and the latter a form of subjugation. Solihull in general, and boarding in particular, was I think an attempt to enhance virility through enforced subjugation. I guessed at the time that it was based on the army’s means of socializing. It makes sense that a soldier fearing for his life needs to be totally subjugated, for example to charge into enemy fire. Basic training enhances his virility by subjugating him, gets him to the point where he is so subjugated and his virility so enhanced that he can charge into machine gun fire.

But what a pupil needs to do does not cause him to fear for his life, far from it. The older boy or teacher seeking to enhance the pupil’s virility through subjugating him is on a fool’s errand. What purpose did that kind of bending over, that kind of excessive subjugation, serve? English education when I was at Solihull had not yet ratcheted back from the Second World War or British imperialism. Solihull’s pupils were being raised for a calling that was almost extinct. In short, the excessive subjugation was stupid and dysfunctional as well as terribly unpleasant and mean.

During the summer of 1966, at home in 18 South View Road with Tiddles on my lap. I was 13: she was 17, and her days almost numbered. The armchair is one of those that matched the sofa in the Cardiff pictures, before it was covered with new fabric.

At the time, it mostly hurt. I calmed myself down and dried my eyes before rejoining the other boys, and for once did not feel little. Being caned had its status. I would never have sought to be caned, because it hurt too much and was offensively humiliating. I mistrust the phrase “bend over” to this day. When it happened in front of our little world, when the hole appeared in the roof of the assembly hall and word circulated that Dougal and I each got three or six for making that hole, there was subdued respect among many of the other boys.

For a change, I felt smaller but bigger. I needed to be beaten until I cried to feel big at boarding school. Needless to say, that was not a sustainable pattern. My solitude in this hardened crowd continued, I never surmounted at the school the picky eating of my childhood, my interpretations of all that happened to me there remained colored by misery and more than a little sense of being persecuted, and all in all I returned to feeling smaller and smaller until, inevitably, I fell ill.

It was not a dramatic illness, but it compounded my increasing sense of smallness until I felt like almost nothing at all. The school treated illness responsibly in general, but there was an undercurrent of intolerance of any sign of weakness. My initial claims that there was a bubbling sound in both my ears and that things were not right were ignored. Thus denied, I felt suitably miniscule. Although I knew enough to know that a mistake had been made, I felt far from that rational at the time. It was raining the evening that I decided that the ears hurt too much. There was no phone that I had access to inside the grounds.

When the impulse came to call mum and dad again, something that I had not done in pain in the three months of this term, I had to sneak outside the grounds in the rain. Simon and Garfunkel again: “A winter’s day, in a deep and dark December. I am alone. . . “. (From “I am a Rock,” written by Paul Simon, and performed by Simon and Garfunkel). Sneaking out was a caning offense.

But I thought that I was sick enough to justify parental intervention, and hoped that I would not be reproached for doing whatever it took to obtain their help. It was it so hard to sneak out of the boarding house and down the driveway. There was almost certainly no-one around, and if anyone had been there distinguishing my small figure from all the other small figures would have been impossible. The phone box was a mere twenty yards from the bottom of the driveway. I was not in prison, but somehow the School had managed to instill the fear of God into the hundred or so boys in the boarding house. It was not a rational fear that held me back, but in retrospect it was depressingly powerful. How easy it is for misplaced authority to emasculate its charges, even a milling throng of bright adolescent boys.

A page out of my Latin notebook. You can tell it is a notebook and not an exercise book that was handed in to the teacher because of Cranny’s comment (some times he was called Dick) on the third line down. Latin was always a challenge!

I was scared scurrying down the dark driveway and out on to the lighted street, and the phone box on the Warwick Road was a sorry shelter. The raindrops trickled down the box’s miniature rectangular windows, glistening in the headlights of the cars driving by. I peered at the cars passing by right next to the box, and dialed the operator. Could she please call Marlow 2450 and ask them to pay for the call? Of course I didn’t have enough money to pay for the call myself. Mum and dad knew me well enough to know that I would not bother or worry them without good cause, and it only took a few sobs on my part for them to hang up to call the School. Suitably chastened, the School immediately made an appointment for me to see the local doctor again, and this time he declared me to be suffering from ear infections that required treatment with antibiotics.

I spent the next week in sick bay, the two or three beds in a separate room reserved for boys who fell ill, spending my most miserable birthday ever, my fourteenth, alone and sick in a creaky bed secluded from the other boys principally to protect them from infection. I have appeared more down to others at later periods, after divorce for example, but that week in sick-bay was the lowest point in my life.

Mum and dad sent a birthday cake, which the school allowed to be delivered, but I just worried about whether it made me appear a mummy’s boy, which I certainly was. Every night I heard giggling from the dormitory next door, my dorm, and was convinced they were giggling about me, mocking me or worse. I don’t remember if Cranny came to visit, but doubt it. A couple of boys did, but what do you say to each other anyway?

The Christmas vacation followed shortly thereafter, and mum and dad sent me straight to see their local doctor to see if the infection reflected any other problems. He told us that I was very run down, a diagnosis confirmed by my terrible skinniness in photos from the period. When they asked him if I should remain at Solihull or transfer to the local grammar school, the doctor recommended the latter. Dad checked with Ernest Hazelton, the Headmaster of Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School in Marlow, and he advised changing schools immediately to enable me to prepare for the serious exams that I would need to sit at either school in eighteen months. It did not take them long to decide.

During a short visit to Solihull School in 2008, I took this photo of the sign commemorating the tree that Simon helped plant during the Queen’s visit to the school. Oddly enough, my memory saw the tree in a different place, prompting the question whether the school moved the sign because the tree that the Queen actually planted was ailing.

As suddenly as it had begun, boarding was over. It had lasted just one year, 1966, a year that remains more than forty years later the worst in my life. I barely felt elated at this long dreamed of, passionately desired, desperately hoped for, and finally unexpected development. I barely felt anything anymore.

When I look back at my rise and fall as a scholarship kid at a public school, neither the ups nor the downs were as extreme as they felt at the time. I was happy as a day-boy because I was with nice, smart boys, and unhappy as a boarder because the other boarders of my age were prematurely hardened and not as smart. As a day boy, I lived with mum, dad and Sue. As a boarder I lived with a house full of lost boys and Cranny after his mother abandoned him.

There was a minor post script, because dad had already paid the fees for the next semester’s boarding and asked for them back on the ground that their school had made me sick. Naturally enough, the school did not see it that way, and I was called to talk to some members of its Board of Governors. They were pleasant enough, and I found myself almost apologetic that I had not returned to the school for more, almost embarrassed that I had “run away,” as they seemed to see it. That is a useful insight into the effects of institutional abuse on a child. However much I knew that I had done the right thing for the right reasons, it felt like failure to leave the abuse behind to protect myself. A Stock doesn’t quit.

The School House in 2008. The dining room of my era faces us on the ground floor, with the boys’ common rooms above. My memory sees high hedges close to the wall facing right.

What was true in my feelings that boarding had been just awful, a feeling that remains with me to this day, was the way that it constantly made me feel smaller and smaller. Being homesick in and of itself made me feel small and inadequate for needing my family so much more than those around me, even though I was only thirteen years of age. The effects of feeling homesick were reinforced by the school ethos that homesickness must be repressed and surmounted in order for the boy to develop as a man. On top of the ever-present peer pressure to become hard were the enfeebling consequences of not being able to conform to the social norms that the boarding community imposed, principally acting tough and not studying. Is it any wonder that 1966 ate into my self-confidence and self-esteem, leaving me with emotional blockages which will remain with me in part until my dying day? Even those blockages made me feel small. It was a vicious, vicious circle.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 16 Catholicism Lapsing

Previous chapter: Chapter 14 The Scholarship Boy

If I Only Knew: table of contents