Peter Stock, dad’s only cousin on his father’s side of the family. Dad’s Aunty Alice, Peter’s mum, willed Sue and me this photo after she died (dad predeceased her). Our family already had a copy. It must have seemed a cruel twist of fate to her that while her son was simple-minded, dad, Sue and I were all so very bright.

Which brings me easily around to organized religion. Catholicism, even religion, has never played that significant a role in my life, even when I tried to make it do so. I regret enormously what I perceive as a lack of spirituality in myself, a lack which I attribute in part to the emotional blockages brought on by serially moving house and community as a child and by boarding. Whether organized religion succumbed to my year as a boarder or simply to the Godless times that we have been living through, I don’t know. But I know that boarding arrived at a bad time in terms of my relationship with the Church, which had been progressing in fits and starts but had been progressing. When boarding was over, it was a bad time for religion in terms of my age and approaching adolescence. After some stuttering efforts upon arrival in Marlow to pick up the thread where I’d left off in Dorridge, I just let it drop.

My religious formation began normally enough, with mum swearing an oath to the Catholic priest who married her to dad that she would raise us Catholic. The daughter of Irish immigrant families, she was born Catholic, and dad was nominally Church of England, a mild-mannered kind of protestant. The priest was thus entitled, I think obliged even, under the rules of the Catholic Church to condition his agreement to marry her on her agreement to ensure that her progeny were not lost to the Church. This, of course, was for the good of the progeny and only of incidental benefit to the Church!

Dad was what you might call an affable atheist. He was not going to impose his particular brand of religion, one based in its absence as a creed, on mum or on Sue and me. He will have gone along with whatever promises the marrying priest asked for the sake of peace in the impending union and because it did not really matter to him what religion mum practiced herself. As for Sue and me, he would leave our religious education to mum. He almost certainly will not have imposed his atheism on that priest, for similar reasons. Why worry him unnecessarily about the potential doom facing these potential Catholic offspring at the hands of this . . ., this atheist! What counted for the priest was at bottom what counted for dad, educating children with some sense of right and wrong, some framework for approaching the world correctly. His atheism was not a badge that dad wore, but it was privately real and important for him.

As I grew up, I wondered from time to time where it came from, and think that it was from sickness, the terrible illnesses that his parents suffered through. It may have been the changing perceptions brought on by the industrial revolution, or it may have been the heightened expectations of a world steeped in science and already able to cure infections, but religion has lost its palliative role. Where once the church gave consolation to the many terrible victims of sickness unto death, now it was beginning to be asked to explain why God permitted so many random acts of insufferable cruelty. When Sue and I buried mum in 1996, as she had willed with her parents in Erdington Abbey in Birmingham, the priest paid a great deal of attention to our portraits of all that she had suffered during her many years of chronic illness and pain. We weren’t asking him to explain why God permitted such things in those whom He was supposed to love, but the priest was addressing the question anyway. My guess is that the Church has identified the artificially prolonged suffering of modern times, because in many cases there is enough medical help to keep the patient alive, just not enough to cure him or her, as a significant cause of disillusionment with its own form of organized religion. The weakness of most organized religion is that it promises too much.

Grandma Stock in around 1960. She did not like her hands and body to be photographed because they were tied up in knots, literally, as a result of the rheumatoid arthritis which had afflicted her from a relatively young age. In her married life, she looked after dad and an ailing husband until 1944. After dad married and moved on, she was left alone with her own progressively worsening ailments.

Dad’s atheism may well have been generated by the failure of religion to cure. He was born at about the same time as his cousin Peter, his Uncle Bert and Aunty Alice’s son. Bert and Charlie, my grandfather, were brothers who both worked for the GWR in Paddington. Both lived near to each other. Peter turned out to be simple-minded, and by the time he died aged around 40 had attained a mental age of about seven. Nothing could be done about it, except for locking him up in an institution as soon as he grew up physically so that his childish anger in a man’s body could not do real harm. He upset dad no end. The benefit for him was that Aunty Alice threw much of her maternal energy into dad, in particular after Peter left home, and in many ways dad had two doting mothers. He was the bright one, clear-eyed and charming, and in those two mothers may be the seeds of his later bad habits.

His own father’s weak heart really distressed dad too. I can still see him talking about it, the pain on his face years after it was all over. Grandpa spent months at a time in hospitals as dad was growing up, with grandma and dad traipsing for miles each way to visit him as often as they could, mostly on the bus. Grandma’s rheumatoid arthritis was a particularly cruel illness for a son to watch in his mother, involuntarily curling her fingers in photographs as early as her wedding day, crippling her more and more as she grew older. Hers was a classic artificially prolonged pain. The steroids that were introduced in the 1950s as the new wonder drug for people with her condition were effective enough to slow down her physical deterioration, but not effective enough to reverse it. Rather than dying in her early 50s, as she was on track for when the steroids were introduced, she remained in the same level of pain and handicap for almost another twenty years.

To the extent that dad’s atheism was based on disillusionment with a God who could do nothing for all the people most close to him, it conflicted with a central tenet of his own personal morality, a tenet visible in his letting mum, Sue and me do what we wanted about religion. Traditionally, that is called tolerance. But during a period when megalomania was becoming more democratic, when everyone seemed to seek more and more control of the people around him or her, I think that it was something more. Dad instinctively knew that his place in the world was not in charge of everything around him. At times he was in control, but mostly he was just there. He had, in the words of the theologist William F. May, an “openness to the unbidden.”

Alice and Bert (together on the right) with Annie Burrell, their sister in law, before Peter came into their lives. One unlucky card, and both their lives were inexorably altered. This must have been taken in the late 1920s. Peter arrived in 1930.

This is called different things by different people, but it is one of the few things that I see as fundamental to our collective future. Will we escape from freedom, or learn not to be afraid of it, even to rejoice in it, as dad did? Will we run away from the mess of constantly malfunctioning democracy and seek the comfort of a totalitarian protector, as Germany, Italy and Spain all did in the 1930s? A little macroeconomic pain, a jolt of unemployment, and three of Europe’s oldest and strongest peoples dissolved into a protective abdication of democracy and personal responsibility. The most evil protectors imaginable ensued. A little more macroeconomic pain, or a little religious disillusion, and any other country in the world could dissolve into the same abdication of responsibility and adoption of evil. At any time.

Whatever you call it, openness to the unbidden, antiauthoritarianism, the assumption of freedom, dad had it and preached it by example. His approach to the rest of the world almost always avoided making judgments or otherwise controlling from on high. Only in his atheism was he perhaps running away from the unbidden, escaping from freedom. To some degree death is the unbidden. But as it is inevitable, it is a manageable unbidden. Sickness is less inevitable, and thus more unpredictable, more unbidden, a constant proof that our control over ourselves and over the people around us is ineluctably limited. Sickness is a manifestation of freedom. As science and technology can accomplish and program more and more of who we are and what we live, we need the unbidden to remind us of our humanity, and some would say that we need the unbidden to remind us of God.

If dad’s atheism reflected the manifold illnesses of his upbringing, then it betrayed his openness to the unbidden in ways that he did not betray them elsewhere in his life. He was almost never authoritarian with Sue and me. There was a kind of discipline, but his control of us children lacked any exercise of brute adult power over us. He wanted to influence us in the direction of his liberal morals, to be tolerant and empathic as he was. I have never found in myself his patience as a father, and am in awe of how he managed to avoid authoritarianism when confronted with all that I threw at him as a child. He must have wanted very badly to remain open to us and not force us into some kind of submission. Children are the ultimate unbidden. How we react to them defines whether we can grow out of our adolescent control fantasies. When the children arrive, will we learn ourselves to ease off on trying to control all around us as a means of overcoming our basic anxieties? Or will we learn again to go with the flow in the face of adolescent excesses? As a father, I have had great difficulty answering these questions correctly. Dad never seemed to.

Dad’s Uncle Bert with dad and me in his and Aunt Alice’s back garden in Cowplain, near Portsmouth. Alice and Bert loved their gardening, as did dad. This photo was taken during the summer of my year boarding, 1966. Don’t I look emaciated?

He had his little proverbs. They were each repeated often, almost insisted upon, and together made up their own kind of education. “You can’t win them all,” was one of the more regular, along with its close cousin “bound to lose a few.” Dad did win a lot, at school, in the army, with women, and in his career. He wanted to win them all, but he reminded himself and us frequently that there were always some that would be lost. Perhaps he wanted to reduce the pain or frustration of losing, perhaps he wanted to point out that losing was as much a result of luck as of personal failure. Either way, these were good little proverbs to learn early in life.

Then, after I actually won something, he typically darted out with a smile on his face: “who were you playing, then, the blind school?” No encouragement of inflated egos in our house! “Self praise is no recommendation,” another in the same vein, was my favorite. It is a good

commandment: simple to understand, and very hard to follow. Modesty and discretion are very hard to teach, especially to a child. Dad managed to do so in a way that retains vitality 25 years after he died.

Not all his little sayings had morals. There was “sort yourselves out, lads,” typically uttered as he prepared to overtake Sunday drivers on a two-lane road. Whenever someone burped audibly, he would stand up straight and intone respectfully “Good morning, vicar!” One that perplexed me was “no peace for the wicked!” It made sense, but he had little peace, the family as a whole had little peace, and surely he didn’t mean that we were wicked? “Patience is a virtue, a virtue is a grace, and both of them together make a pretty face!” I think that that one, oft repeated, was especially for me. Dad was certainly not impatient, and I certainly was. Did it help? Maybe not, but it was always clear that impatience had its downside.

He called himself “Jim-lad,” said with a smile, and normally with a particular tone of voice, clipped, instructional, but friendly. “Get your finger out, Jim lad,” he would tell himself when stuck in the middle of something, bringing a classic English phrase of dubious origin into his repertoire. At school he had been “Ticker,” as in tick, tock, ticker stock. For

us, he was Jim-lad.

Dad at Slough Grammar School in around 1942. He left school to join the army in 1943. There was a war on.

When I try to write about religion, Jim-lad fills my mind and heart. It was like having a live-in guardian of morals, a live-in priest. He knew how incredibly lucky he was, with his brains, his looks, his charm and his natural athletic ability. He played for his school, and that was the measure of schoolboy sporting success in England. He was selected for the school team in four different sports in 1943: football, cricket, field hockey and tennis. Or maybe he only played tennis at LSE. He was a track star too. He compared himself to his cousin Peter in the institution with no way out and no brain to speak of, compared himself to his mum and dad, each more or less crippled in more or less pain living more or less hopeless lives. We learned to be as grateful for our gifts as he was for his. We learned to see ourselves as fortunate, as he saw himself as fortunate. We learned concern for the unfortunate, for the poor, the sick.

We learned without realizing it about prejudice and ethnicity. Gerald Rose, dad’s colleague and friend who had launched Mr. Kipling Cakes so successfully and durably in the early sixties, was with his wife Sylvia a regular visitor at 18 South View Road. I did not learn that he was Jewish until mum and I took the Roses out to lunch in Marlow about thirty years later. His faith was not considered noteworthy in dad’s world. Years later at a birthday party at Law School, Richard Boldt announced with a gleeful smile that I was the only “goy” present. I had not noticed, and was surprised that anyone else had. “So what?” I asked. That was the after effect of a careful moral education.

Dad was much more deliberate in our education than mum. Ethnicity was barely a subject of discussion at our home, which had two religions already, and if it was discussed the purpose was to sensitize Sue and me to its downside. We did not meet or identify people by their nationality or ethnicity, a posture facilitated because we rarely met anyone with a different color skin either. I don’t remember being told a visitor’s background except to clarify an accent or something that the person had said.

This striking young man is Paul Robeson: how many years was he ahead of the folkies and protest singers of my generation? AP Photo/Courtesy Paul Robeson Jr., photographed at Madame St. Georges studio in London in 1925, the year dad was born.

But we were told about a Jewish guy in dad’s class at LSE that we never met. Dad never did tell us his name, or at least I don’t remember it. He said that he was very able, one of the best in his class in fact, but unable to find a job doing personnel work, his chosen career, because he was Jewish. He eventually joined Marks & Spencer’s, a British department store chain which served as a refuge for able Jewish business people excluded from participation in the world of UK business. To say that he prospered would be an understatement. According to dad, he took over the stores’ modest food departments. That business expanded and became a benchmark over the years, until he became one of the four Managing Directors that ran Marks & Spencer’s, very successfully. Food became and has remained M&S’s great distinguishing characteristic. By 2007, there were now small grocery shops called M&S Food on High Streets, in stations and petrol stations all over England. These commercial descendants of dad’s LSE classmate who was not able to find a job in personnel work stand as a stark reminder of the quiet virulence of prejudice in post-war England.

From dad we learned about Paul Robeson, who was not a friend of the family or a colleague of dad’s, but nonetheless became a part of family folklore like M&S’s Managing Director for Food. Whenever we heard Robeson sing, normally on Radio Luxembourg, the less legitimate radio station broadcasting from a boat in the North Sea outside British territorial waters to escape government regulation, dad would explain that the US Government persecuted him because of the color of his skin and because of his political beliefs. I didn’t understand what communism meant or portended, but I knew instinctively that no man with a voice as beautiful as his could merit punishment for what he thought. Paul Robeson singing “Ol’ Man River” is a unique evocation of passion and fury roaring through that incredible voice, and the little changes he made to Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics say it all. In place of “I gets weary and sick of trying, I’m tired of living and scared of dying,” Robeson sang, “I must keep laughing instead of crying! I must keep fighting until I’m dying!” (written by Oscar Hammerstein, modified and performed by Paul Robeson). It is not hard to see why the US State Department restricted his travel, the concrete manifestation of the stupid prejudices he lived in and through. I didn’t really understand the changes in the lyrics, but I knew how Robeson made me feel.

Of course, at that age I saw very little of what dad was teaching. When I did see it, it was fleeting and occasional and not linked to what it meant. They say that youth is wasted on the young. It is more accurate to say that maturity is wasted on the old. How it could have helped me all those years ago!

Beginning in Birmingham, Mum took Sue and me to church every Sunday. In part, she was trying to satisfy the edge inside me, trying to give me a framework for life and its passions. She certainly had no idea that she was living with a priest. The last thing that a priest would do is womanize. She knew that dad had done so in Cardiff, and secretly and privately suspected that he was still doing so. He was away on business one or two nights every week, visiting distant factories and offices, negotiating with unions calling wildcat strikes or with lawyers on employee benefits. All required by his professional duties, of course, but all a bit too convenient for mum’s taste. I didn’t see any of that either, and mum never confirmed her fears. But she would not, would she, because to admit her worst fears would have been too humiliating for her.

Mum decided to prepare Sue and me for confirmation, the Catholic rite through which a person’s faith is confirmed. The older, I was first. From her modern point of view, her children’s faith was only supposed to be confirmed in an informed and educated manner. I was dutifully sent to Sunday school in Dorridge with Father Taylor, a deliberate part-time moral education. There were only a few of us in the class, and the priest was warm and concerned about his charges in a perfectly appropriate manner. But it didn’t work for me. One example that I remember from these sincere little classes was Father Taylor asking the question of whether Judas was sorry about identifying Jesus to the Romans who were to kill him. I didn’t know, and I didn’t understand the difference when he explained that Judas was not sorry, rather he was full of remorse. What difference did that make? Not a lot at eleven or twelve. But Paul Robeson, the black man with the beautiful voice whom dad talked about and who could not travel or perform because of his political beliefs and the color of his skin, that was real, that was comprehensible.

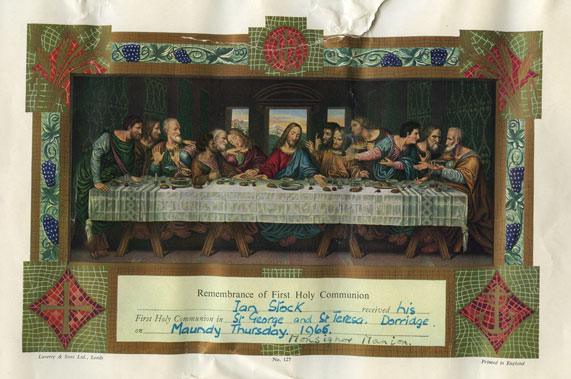

The Certificate confirming my First Communion in Dorridge at age 12. I didn’t follow much of what it was about, or feel much in the way of the spiritual in mass or at Sunday school.

When I moved down to Marlow after that long year boarding, mum took us to St Peter’s Catholic Church most Sundays. Sue attended the parish Catholic primary school located in the churchyard. The young children and their teachers competed for the real estate with the graves. Father Gaffney was the parish priest and a taciturn alcoholic who could get through a full high mass on Sunday, including a sermon, in about 40 minutes. As the norm is more like an hour and 15 minutes, we children were very appreciative of Father Gaffney’s technique. His alcoholism was said to have been induced by the wine that he drank performing mass and celebrating the eucharist every day. That explanation did not satisfy me. I remembered a theologist whom mum had taken me to see in Birmingham the year before I boarded at Solihull. I sat through his seminar only occasionally following what he was saying, which was deep and complicated, I think. But mostly I was distracted. My eyes were glued to the rubber band that he twisted and turned and pulled and stretched around his hands the whole time he talked. I saw the same stress and disquiet in Father Gaffney’s high-speed mass and alcoholism. It was no wonder that dad was my favorite priest, despite his particular weakness. That weakness didn’t matter to me in any event, not until much later in life.

Then there was confession, required of the faithful to purge the soul before taking communion. Confession begins with the immortal phrase: “Bless me Father for I have sinned.” Not an easy phrase or sentiment for anyone, even for a Saint in the best of times. Who wants to admit doing wrong to anyone else? And continue doing so week in and week out? For an adolescent male becoming obsessed with what adolescent males become obsessed about, confession was particularly undesirable. “I spent two hours yesterday evening in bed playing with myself and thinking about a naked woman with long blond hair

covering her breasts and lying on the bed next to me.” Bless me father. Right. “During the day I had a killer boner watching the girls from Bobmore Lane waltzing down the High Street smoking cigarettes with their blouses in disarray. . . “. I never could remember further back than the day before! Then there were the lies to avow, the occasional petty theft, it was all a bit too much. I never ran across the modern abusive priest, but the whole idea of recounting one’s most intimate thoughts to a man whom I could not see in the corner of a church was truly distasteful. That most of these most intimate thoughts were classified as sinful did not help. What was it all for? Three Hail Maries or three Our Fathers was sufficient contrition to cleanse the soul and cure pretty much any boner or lie, and divinity was represented by the hidden man behind the screen in the confessional.

Dad would meet us after church on Sunday mornings, and we would all stroll down to the lock and, like the people on the grass embankment in this 1960’s photo by Ronald Goodearl, lazily watch the boats go by.

The moral education of the church was much less compelling than dad’s proverbs and moral anecdotes. Neither made much of sexual education, but the practice of confession made no sense to an adolescent boy. As teenage years advanced, my attendance at confession first became rarer, and consequently taking communion became rarer. Finally going to mass all but disappeared. I didn’t wrestle with the subject or turn it over in my mind again and again. I didn’t have heartfelt conversations and debates with religious friends or non-religious friends. We barely talked about religion at school. I simply lapsed.

Of the three of us, mum remained attached to the Church for the longest time, but even she stopped going to mass as her various ailments became more chronic and she was in more pain. First her enthusiasm waxed after she joined the local branch of the Catholic Women’s League soon after arriving in Marlow, which became for her the most significant social routine since leaving Bristol and Henleaze. For a while she was the local CWL Treasurer, which kept her well involved in the jumble sales and garden fetes that the CWL ran to raise money for charity and for the Church. Then her enthusiasm waned, beginning

when her best friend, Marian Rooney, a neighbor who was also in the CWL, died suddenly and prematurely around 1969. As her various ailments worsened, her interest in the Lord continued to wane.

We all enjoyed the CWL’s garden fetes, with their stalls, attractions, and jumble sales. It was a small town, with small town excitement. Sue and I got to hang out with other children our age, and run around and go a little batty. Dad was a fan of the tombola, and won something, normally a trinket but sometimes more, almost every time he played. Mum chit-chatted with her friends from the CWL, and helped on the stalls both at the

jumble sales and at the fetes. Thus was the Stock family’s approach to organized religion after we found our own footing.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 17 “Gee but it’s Great to be Back Home!”

Previous chapter: Chapter 15 “(I Wish I Was) Homeward Bound”