(From “Keep the Customer Satisfied,” written by Paul Simon and performed by Simon and Garfunkel)

18 South View Road, Marlow, Bucks. The photo dates from a little later, maybe 1973, but the house did not change a lot over time.

I wasn’t with the family when they moved from Dorridge to Marlow, but doubt if anything during the course of the move would have signaled that our rambling around the UK was over. This was the move that prompted my boarding, and it was with very mixed feelings that I received bulletins about it in the boarding house. Although dad did change jobs again later, he always did so in or around London, and commuted rather than moved us again. As the years progressed, it became clear that he and mum did not want to move again, and no longer felt that they needed to. They loved Marlow, and dad could put up with the commute. They had achieved much of what they had wanted to achieve by the time they got there. Mum had been raised in semi-detached houses in the modest parts of Birmingham by the children of Irish immigrants. The one thing that they had taught her at school was to get rid of her native Birmingham accent and speak English well, with what is now referred to as a BBC accent.

What was the point of a BBC accent if not to arrive in a quaint London suburb on the River Thames with real central heating, a successful managerial husband and two bright and engaging children? Dad was comfortable with what he had achieved professionally, and was delighted to be near some of his own school friends from Slough, which was only about ten miles away. The house at 18 South View Road ended up staying in the family until Sue and I sold it after mum died in 1996, thirty years all told. It was, finally, roots for all of us. I began my own wandering before turning eighteen, but Marlow was and is always home. It was easier to feel that way when mum was still alive, but even years after she left us the feeling is strong. We go back regularly for a few days during the summer. My children remember Higginson Park in Marlow, and whenever they say that they want to go there, so do I.

18 South View Road from the rear, with mum at the kitchen window. The view of the back garden changed over time, and this photo was taken relatively early, 1966 or 1967.

I now drive by the house whenever I’m in the UK with a couple of hours to spare, but its first sighting, on a holiday from boarding, was a let-down. I liked the look of the house next door a lot better, and wondered why mum and dad were so excited about this rectangular block of bricks. It was neither elegant nor particularly well decorated, and the hot water heater caused the wood around it to creak in strange but loud ways unrelentingly throughout the thirty years we were there, but it had four big bedrooms and black tile in the bathroom, and I easily forgot my early reservations. The spare room served as a second living room for Sue and me, after we began developing our social lives, as well as a spare bedroom, and the back garden was enormous compared to the little boxed-in enclave in Dorridge. It had been built not that long before by an Irish family of building contractors, H. Murray & Sons, for themselves, and was as solid as it was unadorned.

My first day at Sir William Borlase’s School, Marlow, known to all by the easy abbreviation “Borlase’s,” was less than auspicious. 1966, the boarding year, had begun a downward spiral that would not reverse for years. I couldn’t help feeling like I was running away from boarding, even if I knew dimly that it was too perverse a world to be able to adapt to. Borlase’s revealed that I not only felt small, I was now physically smaller than the average boy in my new class. Among boys whom I did not know, this terrible fact was suddenly and starkly clear. The problem was not just the boys. My sister was in full bloom by the time I returned from Solihull, and she was two years younger. What kind of injustice was that! And what could I do about it but wait and hope and pray that it would change SOON.

Marlow weir on the River Thames, taken from the lock in August 1966. The bridge is in the background, and the parish church (Church of England) on the right. The wall of the Compleat Angler Hotel, a local landmark, is on the left of the bridge. Marlow is picturesque, with a capital “P!”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. On the way back home from that first day of school, January 4, 1967, I took the bus to the end of South View Road. The school was a mile and a half from home, and the bus seemed at first blush the best way to travel. Walking the short distance along South View Road, I passed by a group of boys and girls from Great Marlow School in Bobmore Lane, the local secondary modern. A little cultural background: at that time in England, boys and girls were tested at the age of 11 and streamed according to ability in grammar schools like Borlase’s, if they did well on the test, or in secondary modern schools like Great Marlow, if they did badly. The inherent unfairness of that system is self-evident: most obviously, it determined intelligence based on ability to do well on tests, when the two are not necessarily related. Those diminished by the system inevitably resented it, as the group of boys and girls that I walked by that afternoon expressed with great simplicity. Confronted by a Borlase’s uniform, they blocked my path, and surrounded me on the pavement so that I could not get away. It probably only lasted a couple of minutes, but they sneered and yelled and taunted, and I can see their faces still, contorted by a resentment bordering on hatred. The resentment was perfectly justified: I knew that already. But faces contorted by hatred are terrible to feel glaring at you. A few of the boys slapped me around a bit and punched me a few times, and the girls laughed and showed their contempt. In retrospect it was nothing too vicious, but I was terrified and fled crying the few steps home.

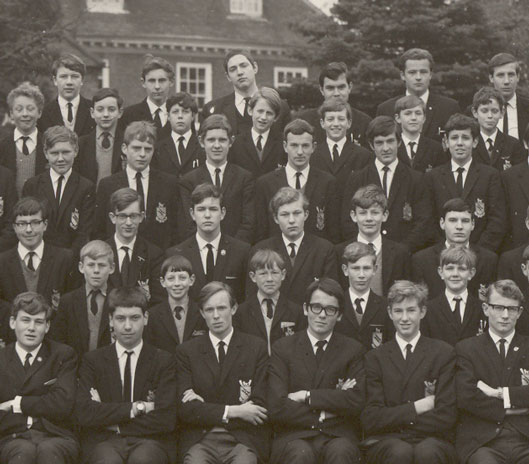

I’m in the middle of the second row from the back in this photo taken in early 1967, with my head tilted and the parting on the right. It is an extract of the Borlase’s school photo. David Milsom is on my left, Phil Slow on his left, and Steve Rodley on his left.

Those random slaps felt like more of the same, more of the violence that boarding school included. But it was not, of course. I was home. Mum felt terrible for me, clucked her sympathy and support, and stroked my hair and wiped away the tears that the terror had prompted. She also immediately called Great Marlow School’s Headmaster to tell him to do something about his nasty, mean pupils. Thanks to the train spotting incident at Tyseley shed and the Cypriot boy who harassed me in the park in Shirley, I already knew about this side of people, even this side of children. With mum and dad’s help, I could work around it. We decided I would bicycle to school from now on, giving me flexibility and speed in case those creeps took it into their heads to pick on me again. They did, of course, from time to time, but only because I would not let them keep me out of the town center on weekday evenings. I avoided them on schooldays with little difficulty. Just because I went to Borlase’s did not mean that I was not encitled to hang out in town on the weekend.

Sir Steve Redgrave is an interesting footnote to this little anecdote about English education and the 11-plus exam. Sir Steve attended Great Marlow School, where he began a career rowing at the Marlow Rowing Club, across the bridge and upstream from the Compleat Angler. Sir Steve was a big boy, and then a big man. I don’t know why he started rowing while attending Great Marlow School, because when I was at Borlase’s, only Borlasians seemed to row, not Marlovians. He was at school ten years after us, and perhaps that rule

had changed. Having started rowing, he practiced and practiced for twenty-odd years. In his case, “practice makes perfect,” as dad used to say. He rowed his way to gold medals in five consecutive Olympic Games. Think about that for a minute. 16 years of gold medals. Needless to say, no-one at Borlase’s has accomplished anything like as much, and probably never will. No-one else in England has ever won so many medals in so many Olympic Games. Sir Steve attained a level of athletic accomplishment that may never be equaled. As a result, the Queen made him a Knight of the Realm. But I bet that the Borlase’s children who all know of Sir Steve still tend to look down on the Great Marlow children, who themselves still resent the Borlase’s children. Such is prejudice, utterly indifferent to reality. Why would Marlow’s most athletically accomplished son change that?

Here is Sir Steve Redgrave, “Marlow’s most famous son,” after winning yet another gold medal. All told, he won gold in five consecutive Olympic Games. By chance, we attended a parade for Sir Steve, complete with open-topped double-decker bus, during our visit to Marlow in 2001.

Borlase’s turned out to be my last school, number six, and I spent three and a half years there, from fourteen through seventeen. Pretty important years. One of the boys I met that first day, David Milsom, has impeccable taste in music and has been a friend ever since. He was a boarder, oddly enough, as was his twin brother Andrew, but was kinder than the boarders I’d been living with, and was kind to me my first day at the school. Any kindness that a “new bug” experiences stays with him. I can still see David, Andrew and Phil Slow at the back of the class that first day, and still feel the fear that being a new boy at school yet again provoked. That was the rule of the game. Not one of those three pushed the point: a good group.

Borlase’s was a state school, unlike Solihull, which was private, and felt more human and less polished, in short a much more pleasant environment for a growing boy. A cottage where Mary Shelley and Percy Bysse Shelley had lived and worked was just along the street from the school, and backed onto its playing fields, although that meant very little to me at the time. There was not that much difference between Bogbrush (Mr. Morton) and

Swatty (Mr. Ansell) in Solihull and Davvy (Mr. Davenport) and Noddy (Mr. Bateman) at Borlase’s: still teachers who really cared, like all four of them, mingled with those who were just doing their job. The boys were similar too, and there were only boys at Borlase’s then, as there were only boys at Solihull, but that enormous difference remained: I got to leave school at the end of every day. The hardness that I feared and resented from some of the boys at Solihull, the occasional negligence of those in charge, was over every day without fail.

Soon after returning home, in the back garden at 18 South View Road. Dad took it, and it’s out of focus!

Mum and dad had not changed, although I expected them to have been marked by the year’s boarding in the same way that I had been. Dad had some sort of a breakdown during that year. He was obsessed with his bodily functions during one of my short holidays away from the boarding house, and sat with us at lunch on the weekend discussing with mum the texture and frequency of his bowel movements that day. Stress went to his tummy, but this was extreme. Didn’t he remember that one did not discuss that sort of thing in front of children, or anywhere in polite society for that matter? Partly it was the anxiety of the new job, of dealing with a major promotion in unfamiliar territory, but partly it was doubt about what boarding was doing to me. For an emotionally restrained Englishman, he showed a lot of reassuring love for me in that breakdown. But by the time I moved back in and started at Borlase’s, he was cured. He was back to his English self-restraint, and I was back to seeing his love, if at all, through interpretation.

With dad in the back garden, on the same day in 1967. Mum took it: it’s pretty much in focus!

Mum was still just the opposite, all emotion most of the time, and she was just delighted to have me back. She had wanted to bring me home within a week of dropping me off at Kineton almost a whole year before, and now she had what her every instinct told her was right. Who was I to argue with the instincts of motherhood? She was almost as delighted as I was to be back. “Gee but it’s great to be back home, home is where I want to be, yeah!!” (From “Keep the Customer Satisfied,” written by Paul Simon and performed by Simon and Garfunkel). Paul Simon wrote “Homeward Bound,” one of my theme songs while boarding, and he wrote that celebration of returning home too.

Tiggy, Sue’s ginger tom, and Honey, my calico cat, also known as Pickle, on the piano stool in the dining room not long after we picked them up from the Slough RSPCA in April 1967. The whole family adored those little cats. Tiggy was run over, we think by a motorcyclist, almost died, and mum and Sue slowly nursed him back to health.

I bought mum and dad a “Teasmade” for their anniversary not long after moving to Marlow. They loved their early morning cups of tea, and the Teasmade prepared them automatically. It was a kettle and an alarm clock built into one small appliance, and the kettle would start to boil the water a few minutes before the alarm went off. The boiling water then obligingly flowed into the teapot that was also part of the appliance and which had tea already waiting in it where it had been readied the night before. After letting the tea steep for a few minutes, mum or dad would then pour it into their cups, add the milk and sugar waiting on a tray, and have their beloved first cup of tea without even getting out of bed. What a great invention! It did have its little problems: for example, the noise of the water boiling tended to wake them up before the alarm sounded. But being able to have a cup of tea without effort first thing in the morning made the Teasmade a much-appreciated gift.

I soon began accompanying dad on his Saturday morning shopping trips down Marlow High Street. Supermarkets were already there, if on a limited scale, but we had particular items to buy at particular shops. The Sunday joint, for instance, was the exclusive prerogative of Clark’s the Butchers, founded several centuries previously, literally, and reliable suppliers of the best cuts of meat in town. Parts of dead animals bled from the

hooks hanging from the ceiling. Dad did the Clark’s shopping most of the time, and mum did a great job of the cooking. Our Sunday lunches were a family ritual, with the roast beef and Yorkshire pudding alternating with roast lamb and mint sauce, and always lovely juicy roast potatoes and vegetables. By this time, she had somehow surmounted her aversion to cooking. Perhaps having such succulent meat to work with helped. Perhaps each of us doing our bit toward the household chores helped. Perhaps she had simply adjusted to the ups and downs of her couple. They were terribly hard for her to cope at first. But she was basically adjusted by our teenage years.

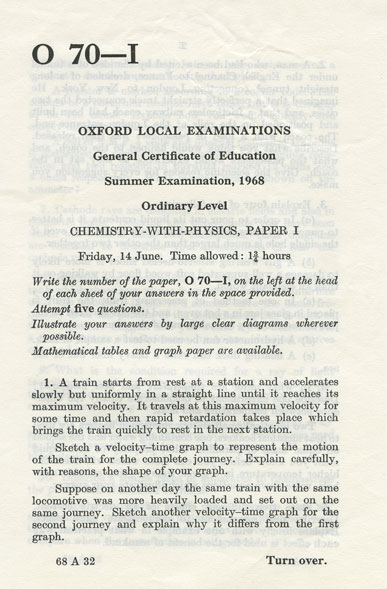

The first page of one of my “O” level exams, found among old school notebooks. I took Physics and Chemistry O levels separately the next summer.

While dad picked out the weekly joint with a little help from his friend the butcher, I seem to remember being responsible for picking out the cats’ fish at the fishmonger’s! Seniority counts for something. Dad and I each bought food at several stores every Saturday, covering as much as possible of the week’s supplies. The guiding principles were to reduce the shopping burden on mum during the week, and to keep the costs of the basics down. I loved doing the Saturday morning shopping with dad. We puttered up and down the High Street, sometime separately, sometimes together, chatting about this and that as the spirit moved us. Our conversations were not always banal or focused on the tasks at hand. I remember asking him one morning, after mulling the question over in lonely moments for quite a while, if the fire in the soul ever died down. I remember his immediate answer: “no.” “But I thought it got easier as you get older,” I persisted. “‘Fraid not,” he added, again without a pause. He looked at me rather sadly. Perhaps it was because he was seeing his boy grow up. Perhaps he wished that it had died down for him.

We also acquired the week’s supply of cigarettes every Saturday morning: before I started smoking, the total was two cartons of 200 Player’s No. 6 non-filtered for mum, a smaller cigarette, and one carton of the larger Player’s No. 3 non-filtered for dad. Sometimes dad substituted Senior Service, and mum would add in an occasional carton of filtered No. 6. They were serious smokers. Cigarettes were everywhere at home, and they smoked everywhere, in the kitchen while preparing food, in bed when waking up in the morning, and constantly while watching the TV. Sue and I didn’t care, at least not then. It was the way they were, that was all.

Sue was just glowing all the time. As I had shrunk and withered during my year away, she had blossomed and at twelve was turning into the striking young woman that Cranny had been so taken with. She had discovered herself and her own capacities, I suspect more easily once she was able to get out from under my shadow. Not that I intended to overshadow her: I adored my kid sister and would not have wanted to put her down in any way. But mum and dad had always treated me as something special intellectually, and had not afforded Sue the same treatment. Maybe it was because of her epilepsy, or maybe it was unconsciously because she was a girl, but Sue never sat for a scholarship to a local prestige school, and never heard all the flattering comments that I heard so much. It must have been such a relief to live without the constant presence of her so special big brother. We were still very close, but the dynamics had changed, and probably for the better.

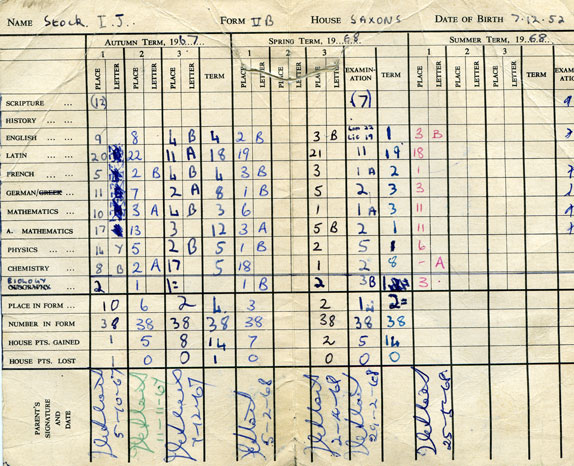

My Borlase’s report card for 1967-8. A bit dog-eared, it demonstrates a poor level of accomplishment in latin. Dad signed it each time the school sent it home. I sat the “O” levels at the end of that term.

Mum’s ailments did take a turn for the worse after my return from Solihull. Her back was periodically “bad,” as she would say, which interfered with her mobility as well as her mood. More significantly, after seeing her local doctor on several occasions as well as a few specialists, none of whom had any clue what these particular symptoms meant, she found a Dr. Lord who ascertained from X-rays that she had three kidneys. She specialized in quirky ailments! Two of them had apparently tied themselves in knots, and needed to be untied. She was duly operated on in Wycombe Hospital, where she spent two weeks in Ward 2B after her four hours of surgery. She was delighted to finally be able to be lodged in a private ward at the hospital. The health insurance coverage provided by dad’s employer to complement the National Health Service permitted this extravagance. It certainly improved mum’s feeling of comfort when she needed it most. She proudly announced that Doctor Lord had removed several pounds of something nasty that had accumulated in her stomach. For years prior to her surgery dad used to tease her about expecting another baby because of her little paunch: now we knew where it had come from.

Surgery rarely seems to be the miracle cure sought by those who suffer it, and this was no exception. Her diary entries confirm my memory that she was regularly poorly even after the surgery, with visits to Mr. Lord almost as regular a fixture as the terse notes to the effect that she spent the day (or three) “in bed.” Her Catholic Women’s League activities were regularly disrupted: “CWL Committee Meeting,” read the diary, “did not attend.” As were her evenings with dad: “Jim went alone,” read the diary, or “cancelled (back).” Then there were periods of a week or two where there was nothing at all. Was she feeling too poorly to make even cryptic notes? Was she upset because she thought that dad was messing around again? Something must have been very wrong during those blank periods, but I have no idea what. I do know that her difficulty sleeping became more pronounced over time, and that her nightly game of choosing which sleeping pill, if any, to take became one of the themes of her middle age.

The immortal (Eric) Morecambe and (Ernie) Wise. This photo is from the cover of an LP that I gave dad for Christmas one year. He loved them. Late in 1963, the Beatles made a guest appearance on their show. Morecambe: “There he is! Hello, Bongo! Hey!” Wise: “That’s Ringo!” Morecambe: “Oh, is he there as well? …”

As for me, the first year and a half at Borlase’s were full of academic work. The UK tends to be obsessed with exams, using them incessantly to make or discover difficult distinctions between people based on the rushed kind of hazing that exams inevitably constitute. I had a selection of exams to take at age 15, called “O” levels. The “O” was for ordinary. Typically, “O” levels were taken at 16, but both Solihull and Borlase’s had a four-year “O” level program for the brighter boys, and that meant that we would take them at 15.

The “O” levels were a big deal. All the teachers at Solihull had talked about them, and now all the teachers at Borlase’s talked about them. By changing schools, I had changed the syllabus for these exams, even the subject in two cases. That sounded as if my Borlase’s studies would be harder than if I’d continued at Solihull, but the new syllabus was somewhat easier and gave me one less subject to prepare. I had promised my parents that I would work hard to make that switch in order to help them justify taking me away from Solihull, and work hard I did. History and Geography were both dropped, but German I took for the first time. I needed to complete a five year syllabus in under two, and spent two evenings a week being tutored privately at “Noddy” Bateman’s house to catch up with his German class. I kept up the hard work until the “O” levels in the summer of 1968. It was a lot easier studying at home than in the boarding house at Solihull, because at home the community supported, even encouraged, my working at the kitchen table after school. It was as if we were all back in Dorridge before the move and boarding.

I took up my old pastimes at home: building things with Lego and Meccano, and of course reading, the great palliative stress reducer. Enid Blyton’s exciting children’s adventures, like “Five go down to the Sea,” were giving way to more grown up material like Paul Brickhill’s “The Damn Busters” and John Buchan’s “39 Steps.” The theme remained adventure, and it was all very reassuring.

My sporting performance never rebounded at Borlase’s to the level that achieved at Solihull before boarding. I did all that I could to avoid the exertions of the prescribed school sports, restricted as at Solihull to rugby in winter. Of course, the inevitable football during lunch and other breaks continued, with the football often played with a tennis ball in the

playground. And later I did take to recreational swimming in the school pool. Letting organized school sports drop was one ofthe initial symptoms of my degradation into late adolescence. I was still very fit, at least until I started smoking, because of the endless football and the bike rides to and from school. The ride home was particularly healthy, with a short, steep uphill toward the end that got the blood pumping before the 200-yard drift home. But the thrill of sport at a relatively high level, learning how to master the fear

and yearning of adversaries worthy of the name, that was gone, and not at all missed.

Nonetheless, Borlase’s gave me the peak sporting moment of my young life. It was the spring before the “O” levels, which would make it 1968, and the “A” and “B” streams of the Fifth Form somehow arranged an informal challenge soccer game and obtained the necessary permissions to play it on the school’s main rugby field, normally the holy preserve of School rugby games uniquely. We were in the “B” stream, a year younger than the “A” stream because of the school’s four-year “O” level track, and this was serious. We all played very well, or at least it felt that way. Nowadays, having seen how well 10 and 11 year-olds can play after a little good training, I’m not so sure. But the way we were playing felt good. Of course I wanted to score a goal, I always did want to score in every game I ever played. And as a midfielder I did from time to time. But mostly I didn’t.

The pigeons scattering before us on Saint Mark’s Square in Venice during our wonderful summer holiday in August 1967.

The Fifth form derby was a tight game, with the score even at 1-1 as we approached full time. The hunger to win this one was pulling me forward out of my typical defensive posture, and I took a pass on a counterattack a little over the half-way line in the other team’s half of the field. Something clicked in a way that it rarely clicked for me, and I dodged and dribbled my way clear through three defenders before lining up to shoot with only the goalie, Chris (“Tool”) Hall, to beat. I sort of fluffed the shot, sending it over Chris’s head in a place that he might conceivably have stopped it. But he didn’t, for which I will be eternally grateful, and I scored the best and most meaningful goal of my young life. It was an important match, and I had made a few great moves in front of spectators.

Getting dressed in the changing room after the game, a couple of sixth formers who had watched the game were nearby commenting on what they had just seen. Their summary conclusion was that it been an average game, which was a conclusion to be expected as we were only Fifth formers, but they added that the goal at the end was quite something. I quietly glowed, and still quietly glow whenever I think about it. Not everyone can score a hat trick in the World Cup Final, as Geoff Hurst did for England in 1966, or run through the

entire English defense and then score, as Diego Maradona did for Argentina four years later, but almost any English schoolboy can make one good run in one relatively important game, score a peach of a goal, and carry it with him, modestly of course, conscious of his own good luck, until his grave.

Being back home brought a return to the routine that preceded boarding. When I wasn’t studying, my bike again became an escape valve, the tool for discovering the town and the local countryside. I spent more and more time riding around, exploring, looking to make friends, finding football games, relishing the return to freedom. At boarding school, I had been locked in at all times during the week except for two hours two afternoons a week. At

home, I was out and about a whole lot. It was like learning to breathe again. And television, almost completely banned for younger boarders, was again a leisure time activity. Favorite shows included the occasional drama like “Z Cars,” some great comedies like the “Morecambe and Wise Show” and “Hancock’s Half Hour.” The totally fab “Top of the Pops” showcased pop stars like Gerry and the Pacemakers, Manfred Mann, the Hollies, the Kinks, Jimi Hendrix, Cat Stevens, the Who, the Stones, even the Beatles, you name them. The Beatles seemed to be on one week in two, and the first time that I saw Bob Dylan sing was on that amazing show.

Same summer holiday. That is Sue and I holding our noses: the smell seeping out of the well was pretty bad. Note the dilapidated building behind us in this Venetian back alley: it still looked handsome.

1967 and 1968 marked our last two family holidays as a foursome. Having wished passionately for nothing other than being with the family the entire year at boarding school, by three summers later I had turned down the family holiday in favor of a week on the River Thames in a rented boat with Joe Kobra, a Marlow friend. Mum, dad and Sue flew off to Italy together, and Joe and I made it on the river as far as Oxford. They had a good time: we had a good time. Families are in constant evolution.

The 1967 holiday was in Lido di Jesolo, the proletarian resort for those wanting to visit Venice, and began with a flight to, you guessed it, Strasbourg. Now Strasbourg has many assets, but one of them is not proximity to Venice. This was classic Jim Stock logic. Mum had been billeted in Venice Lido during the war, and had always wanted to go back in peacetime and see it again. Dad wanted to take her to Venice in peacetime, but could not

really afford to do so yet. But he was already over 40, and tired of waiting for all his very real career advances to turn into the kind of disposable income that they should have already turned into. So he was going to take mum to Venice anyway, and us, even if he couldn’t quite afford to do it right, and we all got on a coach to Lido di Jesolo from Strasbourg, a very long drive in 1967.

Things went okay, to the extent that they can go okay when you’re spending hour after hour in a coach on an autobahn, until we reached the Brenner Pass. They were building an autobahn across that too, but completion was a good couple of years away, and the traffic on the two-lane road it would replace significantly exceeded its capacity. In short, we finally arrived on the Adriatic about six hours late, after mum had made a scene on the coach while we were stuck in traffic that felt like it lasted several of those hours. Right,

mum, that’s going to work! We couldn’t move forward because the traffic was almost stationary and there was no place to pass. We couldn’t turn around because this was the Austrian Alps and there weren’t a lot of alternative routes. Mum shouting at the tour guide, who was as fed up as we were, that he had to do something about it and couldn’t he see that her children were suffering, didn’t accomplish a lot except make me wish that the floor would swallow me to escape from this embarrassment. She was right about one thing: as soon as she started shouting we were suffering! If her children could see the futility of the scene she was making, and we were 14 and 12 years old, why couldn’t mum?

Here’s mum pretending to swim in the Mediterranean in Lido di Jesolo, and dad demonstrating that she is doing anything but. Good times!

As soon as we finally arrived, all this was forgotten. Lido de Jesolo was a discount holiday resort located a good commute from Venice. We didn’t rent a car – the question would not even have come up in those days – and so each time we visited the pearl of the Adriatic, we travelled by bus and boat from the Jesolo hotel, which felt right. Venice itself was a dream. Even when it was grubby, and off the beaten track it was often pretty grubby, it was Venice grubby, with absolutely nothing in common with Birmingham grubby or even London grubby. The buildings were old and often lovely themselves. The canals really were everywhere, and there were only sidewalks and squares around them. We couldn’t afford to stay there, but could afford to walk around soaking in the sights and smells, admiring the myriad scruffy cats that shared the space with the local residents, and stopping here and there for a drink in a café, watching the world go by. We explored the back streets as much as the tourist attractions, and while it was a bit of a shame that we could not afford to try out a gondola or other tourist boat, we could tell that the water buses we used were more real.

In 1968, we again went to the Adriatic. Our destination this time was a city called Pesaro, a picturesque old town with character just south of Rimini, one of the better traps for English tourists. This time, Jim lad got it right. For one thing, we flew into Rimini airport, just ten or fifteen miles from the hotel. So we got off to an easy start, with no coach trips on highways under construction. Then the hotel was very nice, the first time that we spent our summer holiday in a four-star hotel. And we stayed for two whole weeks, not one week, not ten days, two whole weeks. Finally, we had arrived!

The Adriatic beach was so lovely and warm that we spent almost the whole time on the beach. We didn’t know at the time that it would be our last family holiday as a foursome, but we all really did have a wonderful time. That was the cliché postcard home that the English sent at the time, “having a wonderful time. Wish you were here.” Just because it became a cliché did not mean that it was not true. Most of our summer holidays were that way, warm spots that we’ve carried with us ever since.

Mum and dad’s relationship had settled into a type of truce. My guess is that dad admitted to himself that he was doing mum wrong with his womanizing, and thus let her run most of our family life. Guilt will do that in a couple. We had a good example while we were in Pesaro. Poor old Uncle Bert died, dad’s uncle and Aunty Alice’s husband. Mum complained about him interfering with our holiday. As if he had deliberately passed away while we were on holiday! She complained because she did not want dad leaving us in Pesaro to attend his funeral. Realizing that, yet again, discretion was the better part of valor, dad did not fight back much, stayed with us, and the holiday was saved.

I quickly found a group of young people to hang out with on the beach in Pesaro. Most were Italian, and I busied myself learning Italian phrases to be able to communicate with them. They uniformly appreciated the effort, and I appreciated being able to count to 20 in Italian. One of them, an English boy, amused himself by repeatedly pushing me off the diving platform anchored offshore one day, again and again, until the Italians told him to leave me alone. What was it between me and the English? I have no idea. With the Italians, the karma was good. They felt like the Irish to me, all emotion. Miracle upon miracles, I even found a girlfriend. Well, Rosella found me, I think. But she acted like she was a girlfriend. Three of us English boys were found by three Italian girls, and my holiday was assured. Rosella Bufundi. She even did me the honor of crying real tears when I left to fly home.

Mum at the kitchen table with Pickle and Ginge, both enjoying the treats she offered.

These later summer holidays reflected the wonderful ambience during these years in the family. The four of us got along consistently well as Sue and I entered our teens. We were growing up, but the difficulties that entailed were not yet predominant in our lives. We both worried about the opposite sex, me more than Sue, but these worries did not affect our relationship with mum and dad. Each of us still enjoyed learning from them. It was the best time for mum and dad too. They liked us able to reason and discuss more than they had liked us ranting and raving (me) or having fits (Sue). At the same time, they handled us very well as we entered adolescence. Mum in particular really enjoyed making friends with our friends. They both talked with us naturally and easily about issues of interest to teenagers, which I was surprised to discover was relatively rare among the families of friends. Brute authority was notable by its absence. Tolerance and sincere interest in what we were doing and thinking was consistently the norm. I don’t remember when he started calling me “Sunshine,” but by this time dad used that name a lot, and I liked it.

These were the good old days.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 18 “Balls to Ernest Hazelton”

Previous chapter: Chapter 16 Catholicism Lapsing