(“All I want for Christmas is a Beatle,” written by Gladys Benton and performed by Dora Bryan)

John Lennon, from a magazine published by the Daily Mirror newspaper on the Beatles in America. Unless he was playing the fool, Lennon was quite difficult to photograph. I found this magazine, and others bought when I was an obsessed fan, at 18 South View Road after mum died.

John Lennon was shot four times and killed in the entryway to his own home in Manhattan late on the day after my birthday during my second year of law school. December 8, 1980. What a terrible night! He had been living only 80 miles away from New Haven: I had walked past his apartment building, the Dakota on Central Park West, one weekend in New York City not long before. A black cloud of loss washed over me and millions of others. I cried and gave up studying for a few days. Law school is a miserable interlude in any life, designed as it is to help inure you against humiliation and panic by making you experience both often. But it was the shock of Lennon not being there anymore that knocked the breath out of me, not that winter of accentuated intellectual sadism. No more “Bed Peace” in the Amsterdam Hilton; no more lines like “Everywhere people stare each and every day. I can see them laugh at me and I hear them say: ‘hey you’ve got to hide your love away‘” (from “You’ve got to Hide Your Love Away,” written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and performed by the Beatles). No more crazy gestures and wild giggles, never more in his own odd write, no more John Lennon.

And there was the other implicit loss, the one that George Harrison put into words years later when he deadpanned during an interview that the Beatles would not play together again until John Lennon came back from the dead. December 8, 1980 marked the first time that the entire world, all of us who dreamed of their return on stage, knew for a certainty that the Beatles would never perform in public again. What a terrible moment. With the exception of the loss of each of my parents, I do not remember feeling so bereaved.

Maybe that’s why I was once going to write a book with the title “The Beatles and Me,” a whole book. Not that I ever knew the Beatles or any of them personally, not that I ever met any of John, Paul, George or Ringo. No, I have nothing to brag about or gossip about. I was just there when Beatlemania happened, in Birmingham, which is in many ways a lot like Liverpool, where they came from, both industrial cities that grew out of villages during the industrial revolution, Liverpool in the North of England and Birmingham in the Midlands. Liverpool was the home of Liverpool and Everton, two traditional powerhouses of English football; Birmingham was the home of Birmingham City and Aston Villa, two other traditional powerhouses of English football. Fred Smith, my maternal grandfather worked for a time before the cancer got him as a painting contractor at Aston Villa. Liverpool was the home of the railway and of Liverpool Docks, where the industrial revolution’s production was exported, and Birmingham was the home of Fort Dunlop and Rover and Morris motor cars.

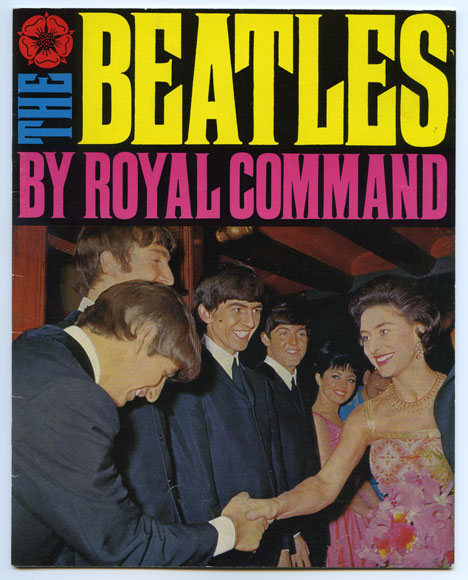

Ringo bowing to Princess Margaret, who herself looks pretty happy to be there, while George beams and Paul smiles. This is the front cover of another Daily Mirror Newspaper magazine found at 18 South View Road, this one published after their Royal Command Performance.

I joined in Beatlemania as much as an eleven or twelve year-old could. I joined their fan club, made scrap books (four of which I still have) out of Beatles photographs and other memorabilia, and mum knitted for me a Beatle jacket, a collarless dark blue and green cardigan with gold buttons that was my single favorite article of clothing before the Carnegie Street era of my later teenage years. Most of all, I listened to their songs again and again and again, as many of them as I could get my hands on.

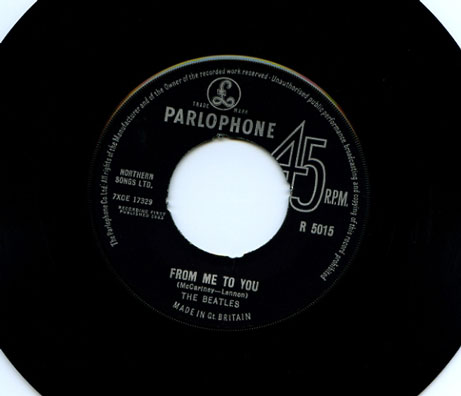

But when I first heard them and heard about them, I wished they’d go away. That’s an inherent conservatism, not wanting to see the favorite of the moment replaced. Cliff Richard was at the top of the charts again in 1963, with “Summer Holiday” no less, and “Please Please Me,” The Beatles’ second single, lodged at number two for weeks before finally becoming “Top of the Pops.” The beat, the Mersey beat, was upon us. It didn’t take long for it to get to me too. “From Me to You” was the second number one for The Beatles in England a few weeks later, and I bought it, loved it and still have it, a mono 45.

“She Loves You,” the Beatles’ third number one, climbed to the top of the British charts twice, propelled the second time by their Royal Command Performance earlier in the month. Already a serious fan at the age of eleven, I watched that concert, courtesy of the BBC. John Lennon told the audience a joke. “For our last number, I’d like to ask your help. Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands? And the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewelry.” The rich laughed. The Queen Mother laughed and waved her handkerchief in acknowledgement of her appreciation of the joke. We laughed, clustered around the TV at home. I know now that the British Royals need to co-opt people like the Beatles, definitely lower class, definitely no social position, but with an appeal that exceeds their own, despite all their social and financial advantages, so that they, the Royals, who give society much less than the upstarts of the moment, will not be replaced. That Royal Command Performance was designed to ingratiate the Royals with the mass of people like us at home in Birmingham. But John Lennon was teasing them and getting away with it. Remembering his accent now, his far-sighted peering out from the stage, because he could not see very well and never did know what his adoring, screaming audiences looked like, brings tears to my eyes, still. Such personal charm, such talent, such depth.

I cut up most of these little magazines to tape the photos into my own Beatles scrapbooks, which is what happened to this one. Arranging photos on pages has been the habit of a lifetime. Only one Beatles Monthly remains intact, number 25 dated August 1965. There are still four scrapbooks full of Beatles clippings and photos.

After “She Loves You” and “I Wanna Hold Your Hand,” the Beatles had a string of number one hits in the English pop charts throughout the sixties, I think it was eleven consecutive number ones, a string that has never been equaled. I bought as many as mum and dad would let me afford, which was quite a few, and listened to them again and again. I pored through every issue of the Beatles’ Monthly that my fan club membership brought to the door. I eagerly watched news items about them, and their press conferences, waiting for the next joke, the next harmless giggle. There was never a shortage of jokes. The entire country went a little bit mad, the girls especially falling in love by the millions, and because they were girls knowing it for what it was. “She Loves You” had the world’s simplest chorus: “Yeah, Yeah, Yeah!” Mothers wrote to mum’s conservative daily paper, the Daily Express, that their little ones, who couldn’t say a word yet, bless their little hearts, sang “Yeah, Yeah, Yeah!” The radio waves were full of their marvelous melodies, their infectious harmonies. Their fans pursued them relentlessly, screamed after them relentlessly, loved them relentlessly.

What did they do in return? They got rich, of course. They gave an entire generation role models full of self-deprecating talent, intelligence fueled by the common sense of the street and humor that burst out of them and left you not knowing whether to duck for cover or laugh. But it was not always a one-way street. Much as it seemed that things worked in their favor, being teen idols and working class heroes had its costs. George Harrison got it pretty much right: “the Beatles gave their nervous systems,” he told an interviewer during his 50s, his last decade. He became a gardener in his home not far from mum and dad’s house in Marlow, dedicated a book to gardeners, and was almost killed by a madman who broke into his house a couple of years before cancer took him. That was a little more than his nervous system that he gave.

As I pored over the scrap books of pictures of the Beatles painstakingly put together out of Beatles’ Monthly magazines and daily newspapers, as I listened day in day out to their songs on the radio or on our little gramophone, as I studiously learned the lyrics that they sang so that I could sing along, as I eagerly awaited each snippet of news on the TV, there was a constant little wish. “If only I could see them one day. Just once, in concert. If only.” I didn’t want more. I didn’t want to know any of them: we were a different generation, I was ten years younger, and no musician. But I wanted so badly, as badly as secretly, because I knew it was too much to ask mum and dad, to see them up close. I yearned to share the colors that they brought into my life and the life of my post-war generation. But it was okay not being able to see them: the music was the key thing, and I could hear that almost as much as I wanted. That’s what I told myself, again and again.

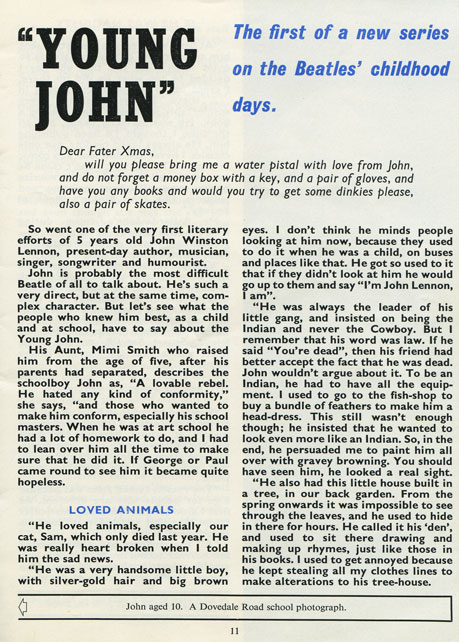

From the Beatles Monthly issue # 25 dated August 1965. Was “Fater Xmas” a deliberate play on words? Let’s hear it for the indians in a world of cowboys! Even if they are bossy little indians.

Christmas was special when we were children. Whatever reasons mum and dad had for being cheap were forgotten at Christmas; well, perhaps not forgotten, but they weren’t allowed to hold sway over our good times. As we had only one ailing grandparent, grandma Stock, and no presents from grandparents, mum and dad always found ways to give us several little gifts so that we did not feel alone.

They gave us paper sacks full of gifts every Christmas. The tourist trips to the leading local toy departments, the decorations all over the house, the occasional midnight mass, and the carol singers coming to our front door, all built Christmas one day at a time into a marvelous time of year. Through a child’s eyes, the emphasis was on marvel. To this day, the only mass that I look forward to is midnight mass on Christmas Eve. In Birmingham, we would drive around in dad’s company car to spot Christmas trees in peoples’ homes and count them, and we would take trips to see the public decorations and the department stores in the City Center wrapped for Christmas. Every Christmas, Sue and I each received one serious present. I don’t remember the details, but one year there was a climbing frame, another a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and another a second-hand model train set.

So Christmas morning 1964 was beginning to perplex both Sue and me when, as we approached the bottom of the last paper sack of presents, neither of us had received a serious gift. It was very confusing. We knew that there was more money around in the household as dad’s job had improved, and so why were there only cards remaining at the bottom of the sack? We were too excited to be preoccupied: the present opening on Christmas morning was the single most exciting time of the year. But it was odd.

I forget who opened the last card, Sue or I. It was addressed to all of us, in mum’s writing. In it were round-trip train tickets for all of us to London. I started leaping up and down and screaming with delight. That was great present: we’d see the Christmas illuminations in London, and maybe do a little shopping during the after-Christmas sales, or maybe go to the zoo or Hyde Park, or even the train stations. London was the capital city of trains, and in our children’s world it was the center of the universe. The Queen lived in London, at least when her flag was flying over Buckingham Palace. We knew that rule already.

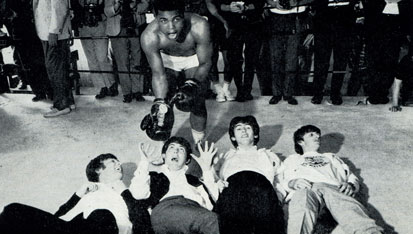

Cassius Clay was training in Florida for the Sonny Liston fight when the Beatles visited Florida. Naturally enough, he invited them down to tell them that he was the greatest. Looks like they agreed with him uniformly! From “The Beatles in America.

Mum and dad were obliged to calm us down to show us what else was in that little envelope: four little tickets (they really were tiny, no larger than a ticket to see a film at the cinema) to the Hammersmith Odeon the very next day, Boxing Day 1964, to see the Beatles live in concert. The Stock family, from the drab suburb of Shirley just outside Birmingham, with their three-bedroom detached house, no central heating, on a tiny piece of land backing up on the playing field of Haslucks Green County Primary School, the shops at the end of the road, a company Ford Anglia to take dad on his commute across town and two bright young children on the cusp of growing up, were going to go a hundred miles to London, a magic city for people all over the world, to break through all that and see the Beatles. All four of them. Live and in person. In a real concert, that would be Sue’s and my first ever concert. What had we done to deserve that? How did I get to live my wildest twelve year-old dream? That Christmas Day of 1964, somehow mum and dad came up with the most perfect Christmas present in the world for Sue and me, and we had tickets, and they were so hard to get, and we were on our way.

From the moment that I realized what was going to happen next, as simply and easily as going to the movies, it was all a blur. It turned out that dad had obtained the tickets through one of his company’s suppliers. As easy as that, he made it sound. I couldn’t believe how lucky we were. I have no memory of the journey down, or of the hotel that we must have stayed in, but the concert stuck. We were in about the seventh row, the four of us next to each other in what felt like a sea of crazy young women. They started screaming before the group even made its appearance and, building on each other’s excitement and longing, they screamed and howled and laughed and cried. It was almost scary before the concert started, and I was glad that mum and dad were there. I don’t remember the lights dimming before the show started, but I do remember that the Beatles were all in light grey suits that seemed to shine, and that their instruments sparkled in the bright lights on stage. They blasted into the music, and the gaiety and the melodies flowed over us. They were partying, partly for us because we loved their music, and partly among themselves, because they knew that we could barely hear it in any event.

I sat in awe, tearing and weeping with my own excitement and the collective hysteria around me. It was collective hysteria: there is no doubt about it. I’ve lived something similar a few times since. There have been other marvelous rock concerts, like the Neil Young concert with Pearl Jam in Paris in the early ’90s, all of them belting out “Keep on Rocking in the Free World” at the end of the show. There have been sports events too, like the night that dad took me to Highbury when I was a teenager in the late ’60s to see Manchester United play Arsenal. 65,000 passionate fans roaring their teams on, and the crowd lunging backwards and forwards uncontrollably between the few metal barriers distributed around the stands. No seating in the Highbury stands then, at least not in our part. Dad and I were squashed and pummeled by the surging throng, unable even to stay together as the passion of the crowd moved us up and down and across and around, in a spastic and terrifying dance following the action on the field. I was suspended in mid-air several times by the adults around me, all of us unable to do anything but be tossed and turned by the surge.

Three months after our overnight stay in London, in March 1965, the Beatles recorded a TV show in Birmingham. We didn’t see them again, of course, but we probably did watch the show on the tele. From “Birmingham in the Sixties.”

But no collective hysteria has ever compared with that concert at the Hammersmith Odeon. I doubt that I have been surrounded by so much naked passion at any other time in my life. What for Sue and me was puppy love was something a lot more serious for the young women all around us. The screams around us were incredibly loud, incredibly passionate. The young women were being egged on by the music, which they knew and which woke up their feelings in the same way that it woke up ours. They screamed louder and louder as the concert went on, laughing and crying at the tops of their longing voices. The music took us all with it, and when my favorite songs came on, I smiled back at them on stage as if they might see a small boy through such pandemonium. I was twelve years old, and I was in heaven. I didn’t really understand what had taken over all those young women, what made them lose as one the British reserve that they had been raised with and turn into lightning rods of uncontrollable desire and longing. But it washed over the four of us, and in my own twelve year-old innocent way I shared it. They played all the number one songs of the year, I think, and they played through more noise than I could have tolerated, and they had so much fun doing it and fooling around when it was too loud to hear themselves, and we had so much fun watching and listening and weeping when we could hear nothing above those terrifying screams. Beatlemania was something beautiful for all of us who were there. John, Paul, George and Ringo may have sacrificed their nervous systems to it, but not at the beginning. At the beginning, it was as beautiful for them as it was for us. In the Hammersmith Odeon on December 26, 1964, we were all still close to the beginning. You saw Beatlemania in “A Hard Day’s Night”, and for one glorious night in London I watched it, weeped it, wondered at it, lived it.

Then we went home, and it’s a cliché but it is true, for me nothing would ever be the same again.

Where did Boxing Day 1964 at the Hammersmith Odeon come from? What was this Beatlemania that bought the youth of an entire country out of a fitful sleep? Why did these four lads from Liverpool, more or less tormented and more or less poor, take over the consciousness of an entire generation? How did they turn us on, so far on, before we even knew what the phrase meant?

One of my first Beatles 45s, From Me to You. I punched out the center later so that it could be played on the portable record player that we brought back from a summer holiday in Italy. “MacCartney-Lennon!”

It was not just the songs, although as we look back now forty years on we realize that the lyrics were sometimes brilliant, their melodies have aged very well, and even their films and videos, arguably the first music videos, do not appear dated. We begin to suspect that their music might well have a classical lifespan. Generations other than my own now listen to the songs incessantly and love them.

It was only in part their lyrics, striking or moving or even quirky as they often were. Their second single, released back in 1963, effortlessly juxtaposed two meanings of the word “please.” Dad’s favorite Beatles song was “She’s Leaving Home” on Sergeant Pepper’s. John and Paul collaborated on the lyrics, about a young woman who left home to meet “a man from the motor trade.” Paul started out the writing: “Father snores as his wife gets into her dressing gown, picks up the letter that’s lying there, standing alone at the top of the stairs, she breaks down and cries to her husband, ‘daddy our baby’s gone!” In comes John: “Why would she treat us so thoughtlessly? How could she do this to me?” Then for the chorus John and Paul bouncing off each other: “She (‘we never thought of ourselves’) is leaving (‘never a thought for ourselves’) home (‘we struggled hard all our lives to get by’)” (written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and performed by the Beatles). Paul, evoking the sadness of her departure with tact and charm, and John, abruptly and painfully spitting out the authentic and inexcusable truth behind it, and the combination was so much more than the sum of its parts. The combination of the four of them was always so much more than the sum of their parts.

There was something about the four Beatles together that suggests that as we evolve genius may become more collective than individual. In his later life, when he was asked about his religious beliefs, George Harrison would say that he did not so much believe as Know. Perhaps the Beatles were in part how he knew. He knew that four scruffy lads with a musical bent but nothing much else to distinguish themselves had created something extraordinary and transcendent. In some small way, something close to a miracle had happened in Liverpool.

They represented something more emotional for us. In all of England’s industrial cities, less than 20 years after the end of the war, the dirt was still plastered on the buildings and in and on the trains, and the national heart was still traumatized by an industrial revolution that had blighted our land and killed off our ancestors like some invading army with its cancer and lung disease. Our cities and their people still suffered the after-effects of a real war that had terrified most of them with its bombs and rockets and infernos in the hearts of our cities, and that had driven us as a country too close to the poverty line and a few of us too close to hell. In most cases, including Liverpool and Birmingham, our bombed-out city centers had not yet been rebuilt after the bombs, even if a start had been made.

Taking a well-deserved bow. In this case, it was at the end of the Royal Command Performance in November 1963, and is included in my magazine of the same name. They are looking up toward their majesties in the Royal Box. Or this could be the rehearsal of that bow: hard to tell.

My generation was ready for something, almost waiting for something. We were tired of the funereal air of England, tired of the grey, the falling drizzle, the dirt. We were the grey, the flat, the morose, the energy of our youth locked up in sympathy with our parents’ hardships, memories and fears, and they were many and real. But there were no other Hitlers on the horizon, nothing to make us hold our breath the way that our parents had been obliged to hold their breath before and during the Second World War. The Beatles were our first proof that Hitler and his ilk were really dead, or at least more than temporarily silenced. They were our first youthful movement out of the shadow of that damned war, finally, our first stand against the dimly-perceived wrongs of the past, our beginning in the colored world, our first love, our first opening to the possibility of something different, more meaningful, better. In many ways, my feelings for them were those for an idealized lover. I was too young to know it, but it was real love.

We all wanted to live something else, and we were all ready to be shown the way. When the Beatles let their hair grow and then their beards, we were ready. When their clothes grew scruffy again, and wild, we were ready. When the Queen awarded them national honors “for services to export,” we were surprised but found the award sensible and richly deserved. When they showed us on Sergeant Pepper’s how meaningless a routine “day in the life” could be, we understood what they meant. When they told us on Sergeant Pepper’s that they would love to turn us on, we were ready. When they told us on the White Album that revolution was not for us, we agreed. When they told us on Abbey Road that “you’ve got to be free,” it was totally obvious. Beatlemania was an entirely reciprocal process. They were so in tune with us, and we were so ready for them. “Come together, right now, over me” (written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and performed by the Beatles). We did.

The last album that they recorded together was the immaculate, almost perfect “Abbey Road.” It was recorded in one last burst of creative energy when they knew that on an interpersonal level their end as a group was nigh. Squabbles and different views of their world conspired to lead them apart. But listening to that album you can have no idea of the disruptions that have already claimed their collectivity. It is an extraordinary display of virtuoso pop, of unique songs strung together by an overabundance of talent. I listen to it about once a quarter, holding on to them still. “Here comes the sun” (written by George Harrison, and performed by the Beatles) sang George Harrison, and it came and it came and it still keeps coming.

The sticker shows the price for this EP, which came out in June 1964: 10 shillings and ninepence. I bought it on the Stratford Road in Shirley. In his liner notes on the back, Derek Taylor writes: “Dip this in gold and give it to your grandchildren.” How did he know?

Some parts of your past never quite let you go. Your longing for them transcends nostalgia and is so strong that they appear again and again, in as many different ways as they can, and you remain as spellbound as you were the first time around.

I developed for a while a fantasy about a concert at Happy Valley School, the small Northern Californian elementary school where five of my children have been educated, happily indeed. The idea for the concert arose when I figured out that the two surviving Beatles, Ringo and Paul, and the two surviving members of the Who, Roger Daltrey and Pete Townsend, play complementary instruments. The Who have lost their drummer, but not the Beatles, and the Who have lost their bass guitarist, but not the Beatles. Ah-hah! What if these four survivors joined forces and played a concert together? Would that be fun or what! This being a fantasy, the chosen site for the concert was Happy Valley School’s playing field, which could barely handle a concert with an audience of a few hundred, and then only if their cars were parked miles away and the audience was shuttled in. The musicians of course thought that this was a great idea, and agreed to donate all proceeds to the school.

I lived the fantasy first through the name of the band, a blend of the names of the two original bands, a pretty silly name to be honest, the “Hootles.” I then made the choice of songs, which was actually quite difficult because with the exception of “Helter Skelter,” which the Beatles recorded on the White Album in tribute to the Who, the Who’s songs and the Beatles’ songs really do have very little in common. Daltrey agreed to play and sing Lennon. As he is an actor, that sounded doable. Townsend agreed to play Harrison, and McCartney to do harmonies with Daltrey. The musicians did informal rehearsals on the deck around our own home, where a limousine could not even make it around the switchback on our driveway. There were long discussions with the County Sheriff’s Office on how to control the crowds and my own role as the announcer for the concert. “Far-fetched,” you may well say, and you would of course be right.

But all that mattered to me in my fantasy world was that it could happen. That is what is so important: it really could still happen.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 13 “Bye-bye Love“;

Other chapters: Chapter 12 “I’d Love to Turn You On”