(From “Summer Holiday,” written by Bruce Welch and Brian Bennett and performed by Cliff Richard and the Shadows)

Here we are in August 1966 on the banks of Loch Lomond. This photo is in my very first photo album, short and sweet, compiled during the school holidays of my year at boarding school. We’ll get to that.

1964 brought our first family holiday by train. Checking mum’s diaries proved to me recently that we had two, with another in 1966, but they are muddled up in my head and when I started writing this only remembered one. Presumably they were taken on a train at least in part for the family train spotter, which was very kind. I was even happier when we were on a train than ordinarily for holidays, and holidays were already a high spot. Summer holidays were quite a family tradition. Dad used to say that he would work hard all year, but that he needed his summer holiday. We went to Butlin’s Holiday Camp in Pwelli, North Wales, one year, Woolacombe in North Devon another, and took the boat to Ostende, Belgium’s principal cross-channel port, in another. Planning for the holiday began shortly after Christmas, and we were all involved and all spent the winter looking forward to whatever we had decided on.

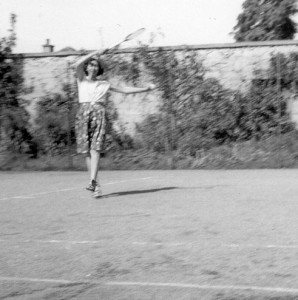

Here’s a rare sight, mum engaged in a sporting activity! The lovely hotel in Nairn, near Inverness, boasted a court.

Sue and I slept in our cabin with a babysitter at Butlin’s, while mum and dad went out, which they must have enjoyed. Holiday camps were all-inclusive holidays with plenty of programmed activities for parents and children, separate and together. Great idea for young families. In Ostende, we rented bikes and pedalos to ride along the promenade whenever we felt like leaving the wide sandy beaches, which was a blast (photos of this holiday are in the chapter on “Success at School”). The seaside was the crucial element.

In Birmingham we were about a hundred miles in each direction from the seaside, and a hundred miles seemed like forever in those days with those roads. Marlow was a little closer, about sixty miles, but not close enough to Sunday drive to the coast. So our summer holidays took us to the sea, every time. Mum and dad saved up most of the year to cover the cost of this one week or ten-day break.

In 1964, we took the sleeper train from Birmingham to Stirling in Scotland, with the car on a freight wagon at the back of the train. This was a one-way trip (we drove back), and on the way up to Scotland the lights of the nighttime scudding by again took center stage the way that they had on the train back from Paddington. Mum and dad had booked two compartments, intending Sue and I to sleep in one and them to sleep in the other, a perfectly sensible allocation. As we sped north out of Birmingham towards Stafford and Crewe, I pulled Sue’s and my compartment window down so that I could feel our speed and see better where we were going, and there was mum, enthusiastically leaning out of her window. After some grumping about mum’s and my windows being down and our tendency to chit-chat back and forth, dad and Sue drew the line and moved into the same compartment, where each apparently slept several hours, and mum and I shared the excitement and the scenery. Each of us slept some, but it was hard. We were much too interested in the strange worlds outside: how could they even think of closing the window and sleeping? What was missing in these people!

Families of four often pair off, more or less happily, more or less pathogenically, and our pairing had been visible for a long time before our sleeping arrangements on this sleeping-car confirmed them. Mum always said that she and I had the same sense of humor. I forget what she said that dad and Sue had in common, but she will have said something. Like me, she always had a theory. This first train ride to Scotland was the summer vacation before I started secondary school, and our pairs were fixed. There would be minor adjustments in later years, but it was mum who cried her heart out when I left for college in California a decade later, when most of what dad felt was slighted, and it was Sue who looked after dad after his first heart attack in August 1972, when I was working at a Youth Hostel in Banff, Alberta.

Sue on the summit of Ben Nevis, looking toward Loch Eil. Between the clouds, I remember the sky as being very blue. Perhaps the photo, already over 40 years old, is losing some of its color.

The train rides to Scotland were amazing, and after disembarking we found ourselves in a different country of heather and narrow winding roads that I for one found more beautiful. The 1966 holiday merits more attention, because I remember more of it and now had a new Agfa 35mm camera. Nothing fancy, and I lived in constant frustration at not being able to buy a telephoto lens or a better flash unit, but I finally could take a few decent pictures. The weather on this 1966 trip was extraordinary for the period. It was warm enough for us to bathe in the Moray Firth east of Inverness, and I have photographs of scrawny little Ian and cute little Sue on the beach. Mum is slim and attractive in the pictures from this vacation, if a little uncomfortable being photographed, and dad young and athletic. He had been one hell of an athlete in his youth, and kept his figure until his late 40s, still a long way off. We drove down the length of Loch Ness, and I for one was disappointed not to see any trace of the monster, although I was well aware that there was no chance that we would see anything. Fort William was our stopping off point.

One gorgeous day there, Sue and I climbed all the way up Britain’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis, while mum and dad sat by the side of the path at about 1,500 vertical feet, watched the other tourists go by and waited for us to come back. The path up went on forever, and turned from dirt into gravel at about 2,500 or 3,000 vertical feet, making the remaining climb up to the mountain’s 4,406 foot summit harder going. I was at an age where I couldn’t stop: I was fit, learning to appreciate my physical capacities, and discovering that I was on top of things and liked being there. It felt fabulous to make the summit.

This is where mum and dad waited for Sue and I to come back down Ben Nevis, at around the 1,500 feet level, not very far up at all. Their faces look uniformly unhappy, and I wonder if perhaps they were annoyed with me for continuing to climb after Sue started crying. She does look more unhappy than at the summit. Note the thermos, certainly full of tea for mum and dad. Mum needed her hot drinks.

But it was all a bit too much for Sue, who gamely kept going all the way up to the summit but spent the last quarter hour or twenty minutes of the climb in tears, just of fatigue, I think. She got over it as we stared out over the Cairngorms: it was one of those classic and rare sunny days where the mist forgets to veil the view and you can see for thirty, forty miles in every direction. We asked other people to take pictures of us, and you can’t tell in them that she had been crying.

Dad and Sue in Morar on the West Coast of Scotland during that same summer holiday in 1966.

I didn’t know whether to feel guilty or not. I could have stopped climbing when she started crying and suggested that we returned to mum and dad. I don’t remember the reasoning involved, but wanted badly to make the summit myself. Maybe I justified doing what I wanted, for instance saying that she would feel better ultimately if we made the summit than if she turned us around. Maybe not. I suspect that the photograph of Sue with mum and dad on our way down from the summit is the only one I have of the rule that we lived by until Sue no longer had fits: don’t upset your sister! Although she had overcome whatever started her crying, it looks as if it resurfaced when we returned to mum and dad. Their displeasure is visible in the photograph.

Sue and I on the pier at Nairn, during that same 1966 summer holiday. We were lucky with the weather.

This is one place where I should ask Sue for her point of view. I don’t remember lording it over her as a big brother is likely to do. But it must have happened, right? Big brothers do that all the time. 1966 gave me a great reason for wanting to get even. Sue stayed at home while I boarded. That wasn’t exactly fair or balanced. I don’t remember getting even, which must mean that I don’t remember how I did. The doctors’ rule that Sue should not be upset was strong, but big brother behavior probably snuck its way around the rule. Just as I have no memory of her fits, I have no memory of lording it over her. I bet that Sue remembers!

A summer holiday of a different kind first made its appearance in 1963. We had all started listening to pop music by the time we moved to Birmingham, at first principally to what mum picked, as dad wasn’t particularly interested. Frankie Vaughn singing “Behind the Green Door,” was one of her favorites: “don’t know what they’re doing, but they laugh a lot behind the green door! ” (Written by Bob Davie and Marvin Moore, and performed by

Frankie Vaughn). She liked all the romantic male lead type of singers, which left Sue and me pretty cold. My early faves (we started using that word a lot later, but it fits throughout pop music) were songs like “Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini,” (written by Paul Vance and Lee Pockriss, and performed by Brian Hyland) as in source of great embarrassment, sung by Brian Hyland, and “The Young Ones” by Cliff Richard and the Shadows. “The young ones, darlin’, we’re the young ones, and the young ones shouldn’t be afraid, to live, love, while the flame is strong, for we won’t be the young ones very long. ” (Written by Sid Tepper and Roy Bennett, and performed by Cliff Richard and the Shadows). The music was sugary, catchy but lightweight, but those were great lyrics for a pre-teen, although I’m not sure that I really listened to lyrics before the Beatles.

This was taken during our previous summer holiday in August 1965 on the beach in Woolacombe in North Devon. We were lucky again with the weather. Odd fact: mum never shaved her legs. So they were normally hidden in photos.

Cliff Richard and the Shadows starred in a wonderful film that had a discrete but powerful effect: called “Summer Holiday,” it was about a charming working lad in London who talked London Transport into loaning him a double-decker bus for a two-week holiday driving and singing around the beauty spots of Europe. That happens all the time in England, of course, and whenever London Transport loaned a bus to a charming lad for his summer holiday in those days, he and his multi-talented friends effortlessly converted it into what we would now call a self-contained motorhome, with bedroom and bathroom upstairs and kitchen and living room downstairs, and then had time to travel. It was a fantasy film, and I was spellbound by the fantasy. The songs were just as lightweight as “The Young Ones,” fun to listen to but with less meaning, but those images of a rolling home, a haven for young people away from home, those images would haunt me for years and years, and still catch my imagination even now. Later Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters would drive their bus “Furthur” through the beatnik years and beyond, and a whole throng of hippies traveled and lived in their school buses. But “Summer Holiday” came first. In 1963 that film opened a whole new world for me, one that would stay with me throughout my life. It was my first exposure to the possibilities of the particular kind of freedom of an RV, a home on wheels. As I grew older, liberty through taking a train or riding a bike to train spot turned into the liberty through my own wheels glimpsed in the film.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 12 “All I want for Xmas is a Beatle”

Previous chapter: Chapter 11 “Summer Holiday”