A moment’s pause with Alex and Charles on her lap during an energetic tour of Disney World in August 2000. It was really hot, as you can see from a photo of Alban and Charles spraying each other to cool down on one of the Disney pages.

Being a mother is the center of Marie-Hélène‘s life. She was the office manager at Kevorkian & Rawlings, the law firm where we met in Paris, and has been at various times a cafe manager at Liverpool Street train station in London, a stewardess for Air France (or was that for the SNCF? Most of these jobs preceded me!) and a salesperson in a book store on the Left Bank: the list goes on.

On the right is from the 1999 summer vacation, taken in one of the boats for tourists that ply the Thames in central London. Daphné and Alban were with Pierre, their father, in France, and the rest of us went to the UK and Brittany (La Grée and St Malo). Tomwas wandering off, as was his wont, when this one was taken. He was looking at the river.

But as long as I have known her, mothering has been her purpose in life.

She shocked me when she divulged that during her youth she could not imagine herself having children and didn’t even care for them that much, especially babies. I’ve no idea where those youthful feelings came from, if not from a girl’s fear of losing herself in her children, but there was nothing of them visible throughout our years together.

The daily life of a mother is frequently missed by the camera, which tends to come out mostly on vacations or during days out, which is where most of these photographs come from. So how can we portray that daily life?

Let’s begin at the beginning, this family’s beginning. For various sad reasons, she moved on and away from Pierre, Daphné and Alban’s father, when she moved into Le Tahu in August 1994. Before doing so, literally years before getting involved with me, she introduced me at length to her children. There was no question of her even dating me if things did not seem to work out between the children and me.

Before the meal at Seascape Resort. This is one of papa’s faves: each looks good enough to eat! This was taken on Mother’s Day in 2006, which gave us some lovely pictures, two of which are on this page.

To be honest, I’m not sure that such a test works, because young children pick up their mother’s feelings for a significant other almost by osmosis, and thus do not really exercise independent judgment about that other. But her intention was clearly to ensure that the children were as okay as possible in the circumstances.

Starting in October 1991, we had a few “childcare” dates. The first happened when she let it be known that Nick, Tom and I would be welcome to join her, Daphné and Alban at “le Jardin des Tuileries” one Saturday morning. It was a touching invitation, in part because “les Tuileries” had a special place in her heart. She had been there when her mother died the year before. I had a great time, as did Nick and Tom, and for once I even have pictures.

One of several taken during our first collective visit to le Jardin des Tuileries. Marie-Hélène and I were years away from actually getting involved, but the children were already hanging out together, if only occasionally. Nick, as ever, evoked something between consternation and interest.

There were the swings and the roundabout for the children, and a cafe for Marie-Hélène’s beloved coffee, all in close proximity. The children ran around in relative safety with distracted parental supervision: no traffic was easily reachable.

We also spent a little time together with the children in Brittany, around La Greé, just a couple of occasions, but it was always made very clear that she was first and foremost with her children.

By the time she decided to move in with me, years later, looking after Daphné and Alban also meant improving their financial health. I didn’t think about it, but it had always been obvious that moving in with Marie-Hélène would inevitably involve supporting her children.

She told me a sorry story of how one day Daphné (then 5 or 6) and Alban (then 3 or 4) snuck away from their parents in a cafe near rue Boursault, where they all lived, and were begging for money on the street when their parents found them. I say “sorry” because Marie-Hélène had relayed the persistent financial problems her family faced, and her children’s begging seemed to manifest their familiarity with these problems as much as children playing roles or otherwise having fun.

Pierre had been an IBM sales guy when he and she got together, but in going into business for himself had somehow managed to reduce his available cash to the point where it had become a real concern for Marie-Hélène, as much as for his numerous creditors.

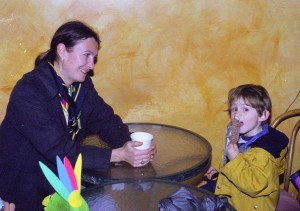

Sharing a quiet moment with Alex in a cafe in Sausalito, California, February 2001. Note the coffee: Marie-Hélène and her coffee are almost inseparable.

The system of taxation of the self-employed in France had something to do with that: I too experienced its downside. You basically pay in arrears, with the current year’s amounts due for taxes and social charges based on the prior year’s revenue. When your revenue drops year to year, and everybody’s does sometimes, it’s hard to meet those still high tax obligations. That’s a torture which he and I shared at different times.

There was another aspect of Pierre’s “poverty.” He had learned from his first divorce that marriage and divorce cost him dearly, and used to boast that he had let his first wife keep the house, everything when they split up. It did not seem entirely unrelated that he never married again.

So as not to hurt her feelings, or so he said, his first wife (with whom he had one child) remained his legal wife through his relationship with France-Lise (three children) and Marie-Hélène (two), giving him a good reason for not marrying either, or any subsequent girlfriend. It was all bit too convenient for me. One of Marie-Hélène’s more perceptive friends described him as a cuckoo, depositing his chicks for others to raise in their nests.

Outside the Santa Barbara Mission in 2001 with her three sons, one or more of whom is inevitably fooling around!

I personally felt that he was committed to hiding his money rather than truly poor, so that the fisc, girlfriends and ex-girlfriends could not get at it, but she was sure that he was broke. By the time she moved out of the apartment they shared he had no car of his own and had appropriated hers. He was supposed to pay the rent at their apartment in her parents’ building, and almost every month whether he would in fact come up with it was a drama.

In short, her and her children’s financial predicament was a real concern when she moved out of the apartment she shared with Pierre. She had put up with his romantic escapades, but could not see subjecting her children to a lifetime of want and financial need. Her children’s needs were as important than her own.

Not that I was ever rich, as she has reminded me upon occasion! When her family moved into Le Tahu, I had already been self-employed in Paris for two years, and finding work as a solo American lawyer in France was a real challenge. But she was able to move in and not worry about where the rent was coming from and not worry about looking for work.

With Daphné and Alban (and Charles coming along fine!) at l’Ecole de Saint Cyr, near La Grée, in July 1995. Denis, Marie-Hélène’s brother, is a graduate of that prestigious military school.

In return, she put her whole heart into looking after Nick and Tom as well as her own children. My boys tended to be more expressive and out there than she was naturally comfortable with, more visibly aggressive, but she worked hard at accepting them as they were.

She was visibly surprised when the Versailles court awarded me custody of Nick and Tom, and their mother extended visitation rights. It was unusual for a father in a contested custody proceeding in France to win, and she probably did not expect it. But nothing changed in terms of her effort for, and calming influence on, Nick and Tom. I was so very grateful. The effects of the divorce on my children worried me sick, and having a calm and caring stepmom brought many sighs of relief.

On the monorail in Disneyland, Anaheim, a little over fifty years after it opened. There’s one of Alex and papa here.

The first hiccup was my failure to earn enough in France after a few years. 1996 saw a drop in income that I could not seem to remedy. Six years before, at the firm where Marie-Hélène and I met, I had drafted and managed the largest acquisition ever then made in France by a US multinational. In 1996, I could barely find work, and what I found deteriorated rapidly.

It’s not all a bed of roses: here we are handing a Charlie tantrum with aplomb at Carmel Mission in May 2001

I felt like I was doing my best to try to stay in France, but must admit that my desire to escape from there was still strong. I had only intended to stay for four years maximum. So perhaps when mum died and I was free to leave on that level (no longer any need to look after her with regular visits and the like), I let it happen. Maybe I did not try as hard to stay as I felt I did.

Either way, leaving France for me to find work in the US was a major upheaval for the family. Not only would it separate Marie-Hélène from her homeland, it would also separate her older children from one of their parents. That is what distressed her the most, and her children too. She, Daphné and Alban would all need to learn a new language, English, and a new way of living. This was definite hiccup from a maternal point of view.

I tried to do what I could to fix things, both the lack of income that last year in France and Daphné and Alban’s loss of the proximity of their father. I spent my entire inheritance on paying for us all until starting full-time work again in early 1998. It was not a fortune by any stretch of the imagination, but only the down payment on our home in Santa Cruz was preserved as my separate property.

The fun side of motherhood! Every year, the stores in downtown Santa Cruz hand out candy to trick-or-treaters. This photo of Charlie (on his mother’s right) and Alex (on her right) shows maman in costume too for Halloween 2007. Note the Santa Cruz Book Store, a genuine tourist attraction!

Arrival in the US did bring the most significant change that our blended family went through during the sixteen years we parents were together. The Versailles court changed its initial judgment and moved custody of Nick and Tom to Sunshine in Paris so that these anglo-american boys would not be deprived of their “native” France. We were down to three children living with us, four after Alex came into the world six months after we arrived.

At the time, this made Marie-Hélène’s life easier. There was just so much to adjust to and learn in the New World. The fewer children to look after while going through that adjustment and learning, the easier for all of us. Except for me. It drove me a bit crazy, just trying to see our missing boys.

The problem was that as it dragged on, this period of having just four children became the norm for our family. Two years is a long time when children are growing and evolving. The relationships among parents and children were recalibrated during Nick and Tom’s absence in France, and the recalibration remained when they returned to live with us. The fine tuning that we had accomplished relatively well when we all moved in together in 1994 was lost by 1999, when Nick and Tom moved back in. The two years away undid a lot of the good work of the first three years.

Life’s a beach: Santa Cruz! Warming up the dynamic duo after an afternoon’s boogey-boarding on Capitola Beach in May 2004. The significance of the two contrasting beach images is a question of temperature. Marie-Hélène feels the cold very keenly, and on the early visit delighted in the warmth of Southern California, even early in the year. Unfortunately, that warmth does not quite extend north to us, and the shivering boys on a local beach personify the difference, one that she deplores!

I don’t want to give the impression that Marie-Hélène did not want Nick and Tom to move back in with us. She did everything that she could to bring them back. The psychiatrist appointed by the Versailles court to examine them and advise on where they should live came to interview us and see us in Santa Cruz. He interviewed Marie-Hélène alone. Without fear of retribution, she could have used that private interview to discretely discourage their return into her home. I would have been none the wiser. A recommendation to stay living with with their mother would have been entirely normal, and could have had a hundred reasons other than anything that she may have said during that so-important interview. But that his recommendation was that they live with us proves that she advocated for such a move, even in private.

Nick and Tom returned to a household where Daphné and Alban were the big kids with the friends at school and the activities and, particularly in Daphné’s case, the clear roles as the older children. Nick and Tom were essentially interlopers in this world.

Life’s a beach: Southern California. Showing Charlie how to swing on a San Clemente beach during her first visit to the US, April 1997.

They didn’t help things by returning with a piece of their mother’s feelings for Marie-Hélène. Both absent parents told the same story. In Sunshine’s case, Marie-Hélène was presented as the evil being who had stolen her husband and destroyed her marriage (in Pierre’s, I had the same role). She had told this story before, when we were all living in France, and it had not been adopted by Nick and Tom, perhaps because they were younger, perhaps because they had the reality check of Marie-Hélène’s presence and caring then. During that prolonged absence, on some level they absorbed Sunshine’s version of events, and returned to us more distrustful of Marie-Hélène than when we left.

The ingredients were there for a deterioration in the relationships within the household. I don’t know how quickly that happened, or even understand why we were unable to divert and repair what had been set in motion by our move to the US. I can’t help thinking that we should have been able to do so.

The proof that we didn’t is visible in Nick and Tom’s respective departures from our home later on, as Daphné and Alban stayed put almost continuously. Most notably, Tom moved back to his mother’s in Paris at the end of 2007 and never came back to us. He must have felt pretty bad at our place to have done that.

Finally, here she is at her her father’s house in Brittany (see here) with her four children, on June 30, 2007. Daphné and Alban managed to join her for a week or so during their summer vacation with their dad. As in most summers, Marie-Hélène spent a month or so visiting her father with Alex and Charlie.

The children who felt like interlopers left, the children who felt that they belonged stayed. I do feel that Marie-Hélène could have used more of her considerable mothering abilities to rectify things after Nick and Tom’s return. But I also see how it was a very difficult task. Not only were the boys giving her a fair bit of grief, prompted I suspect by their mother’s overly expressed feelings, but also she was essentially being asked to help Nick and Tom again be equal to Daphné and Alban, which meant on some level being asked not to favor her own children. It was a terrible bind.