My mum died in July 1996 after a long series of illnesses.

At the time, Marie-Helene’s and my family was busy blending, meaning going pretty much crazy, her two children, my two children and Charlie (less than a year old) all sorting themselves out in a forest southwest of Paris. The living were taking precedence, and I didn’t write anything then about losing mum at all, except in my capacity as co-executor of her estate.

I’ve been going through archives, reducing the number of boxes in the old stable, and recently discovered letters and other odds and ends collected and filed away back then. I took the time to read them (retirement and an empty nest do have their advantages!), and doing so gave me a big jolt. No-one gets over the loss of a parent very easily, although the passage of time helps distill the memories.

I easily go back to the last days we spent together, three or four days before she died. I had brought Nick (then nine) and Tom (seven) over to Marlow to visit her for the weekend – we made occasional visits together from France, although I tended to visit by myself by this point, because mum was so ill – and it was a fine visit. The boys did very well, behaving themselves, only a little bouncing off walls.

She put us all up in a hotel in Maidenhead, perhaps five miles away from her home, because even with only two children out of five she now found collective visits tiring, and on the last evening, the Saturday, I returned to visit her again after putting the boys to bed. That was unusual – I didn’t normally leave them unattended – but something drew me back.

Mum, who been quiet and a tad withdrawn throughout the weekend, woke up as soon as I walked back into 18 South View Road. Her arm was very sore, an unusual and recent symptom, and so she called the doctor to check it out, one of her hobbies. The poor chap duly arrived at the house, as they did at that time in England, and basically asked what we wanted of him. That was a difficult question, and we passed on it. The local doctors did know how ill she was, but also that there was very little that they could do.

After he left, mum and I had one of our chats, full of life and laughter, as if it was 20 or 30 years earlier. I don’t remember what we talked about, just that it felt like her and my best times together, when I was in my late teens and early twenties. Maybe the chat lasted an hour, because it was already late and I was worried about the boys being alone. Maybe a bit longer, because we were both so happy that evening. She always said that we had the same sense of humor; we had been so close for so long.

I didn’t know that I would not see her alive again, but when I left for some reason couldn’t use the front door.

Leaving through the french windows in the living room, directly in front of her on her sofa in front of the tele, I looked back at her to smile an au revoir, and she looked at me “with a kind of wariness or bemused curiosity,” as I described it in a letter at the time, as if she was looking out of a tunnel. Never having seen that look before, I thought about it as I drove away, and again when Sue told me three days later that she had gone.

I have only ever seen that look one other time, in Santa Cruz on the face of Banane, the calico cat we had brought over from France. Banane died the night that she had that same bemused look, inside a tunnel.

Like mum, perhaps she knew that she was saying goodbye.

This is not the place to repeat all that mum did for her family and for Sue’s and my families. Her love for each of us, her efforts on all our behalves, should be visible elsewhere in these memoirs. In particular, her kindness during her last years – the annual passes to Disneyland outside Paris, the constant support – has already been written down here.

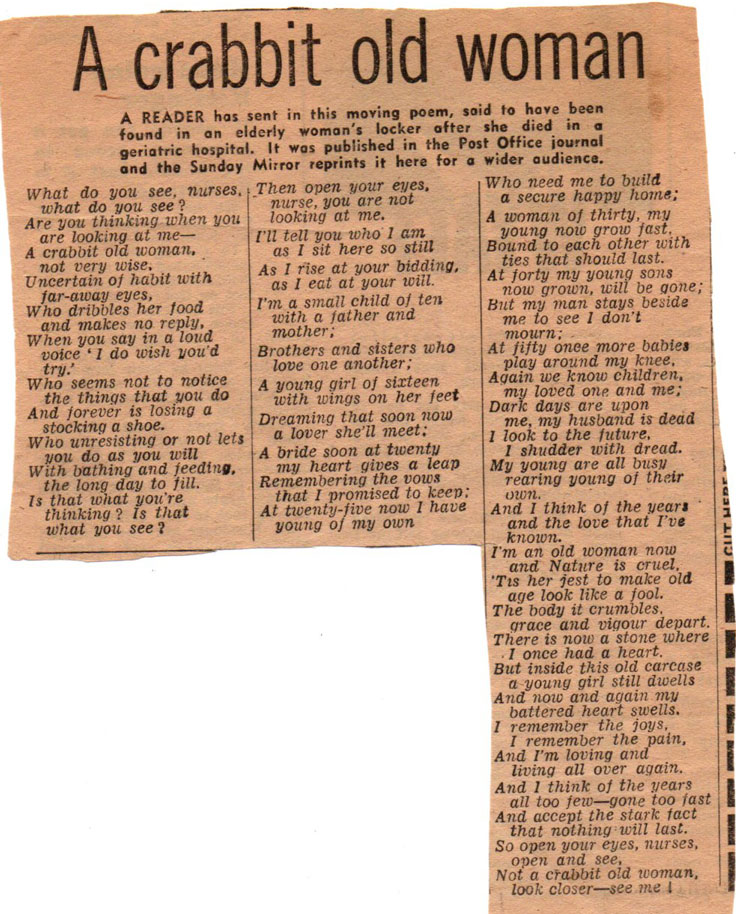

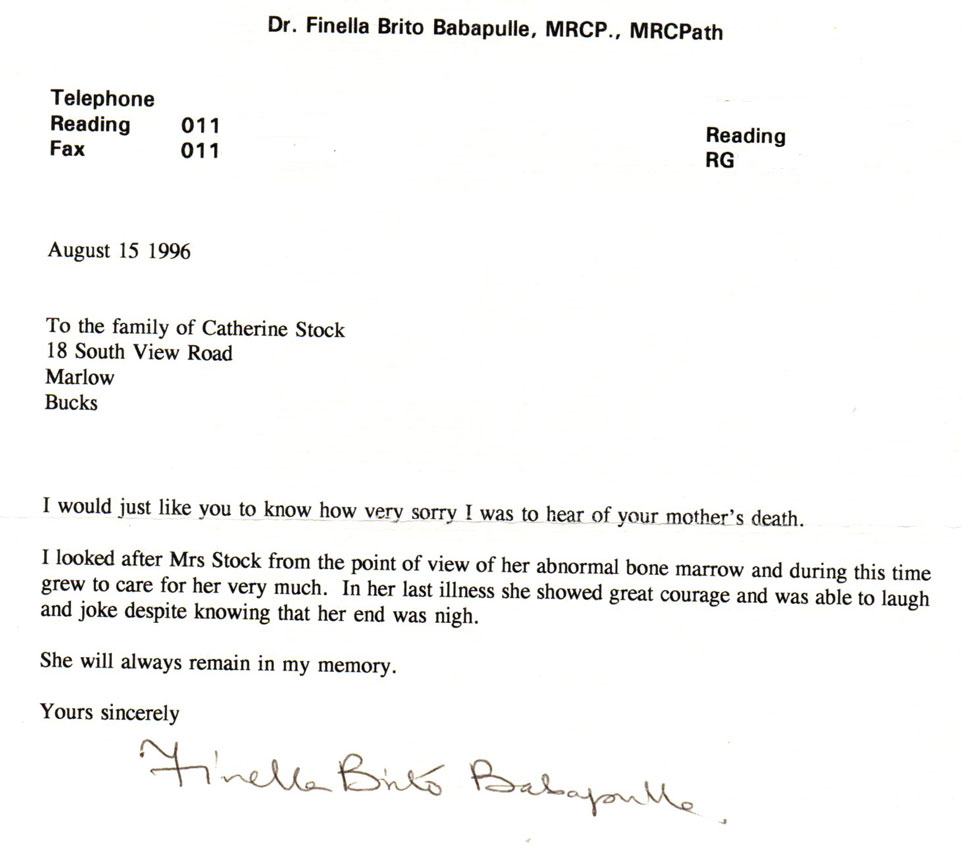

Rather, the documents and scraps that resurfaced recently bring up the sadness in her life as she aged, her solitude after her children had both emigrated, the years of coping with chronic illness, and her courage as the end approached. I mean this post as a kind of tribute to her, honest rather than saccharine, and perhaps a little off key.

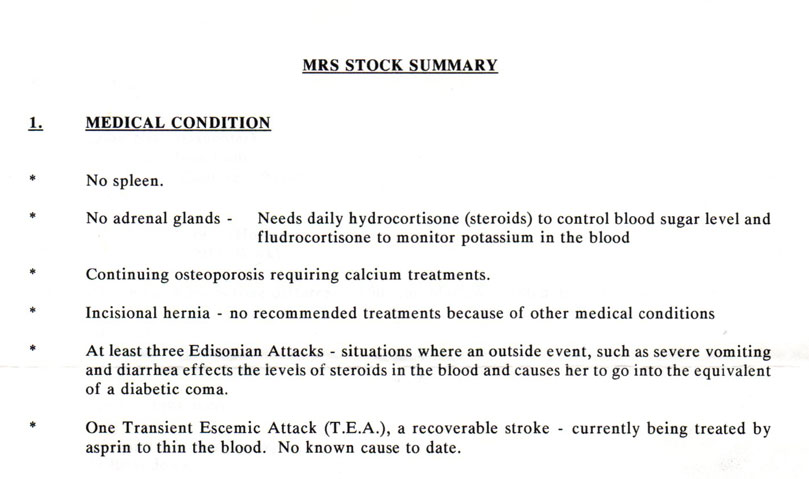

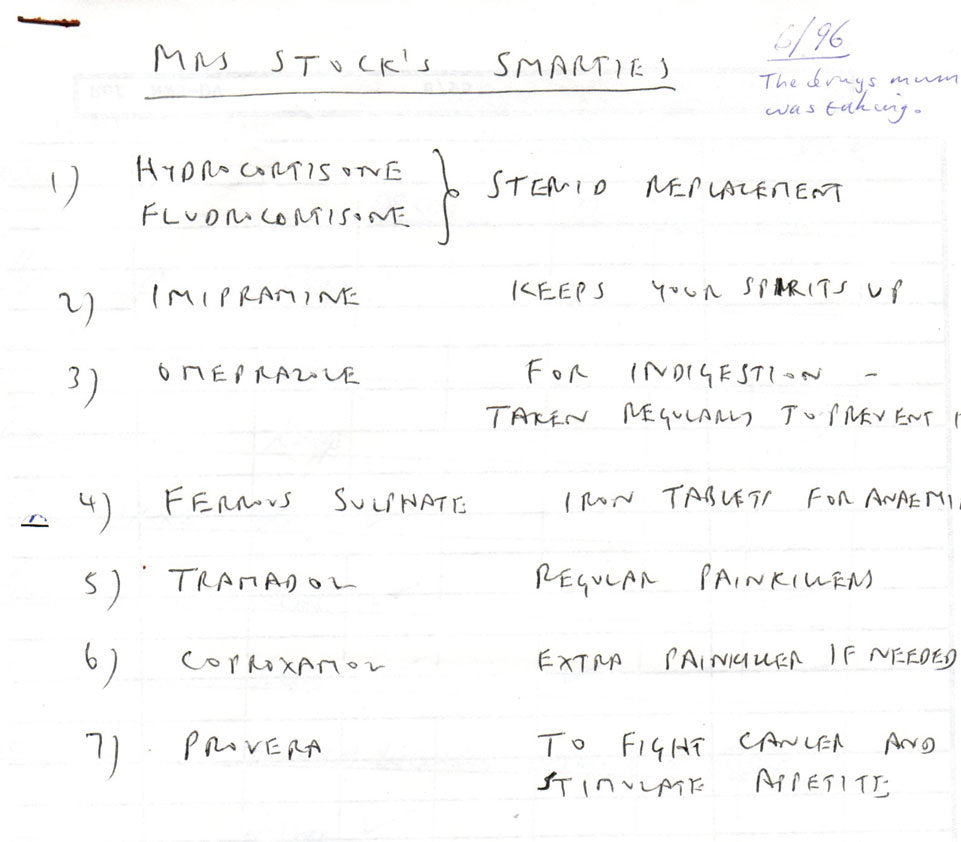

First, the sickness unto death. Mum had been ill a lot during her life, more as the years advanced.

In contrast to dad, who kept his heart problems inside, she also talked about her health a lot: it was, understandably, one of her great interests. A family member’s ill health is hard on the whole family, and harder the more you hear about it. You always want to help a loved one feel better, and it’s frustrating when you can’t.

I suspect that it works the same way for doctors. Mum’s local medical group meant well, but her symptoms were so diverse and insistent, constant only in the regularity of their appearance and evolution, that the doctors in some sense gave up on her after referring her time and again to specialists. As did we in the family at times. So many symptoms, so little that we could do. At times, we felt that she was a bit of a hypochondriac. Maybe the local doctors did too.

But now when I look back, she had very real illnesses, which took extreme measures to fix. The first that I remember well was in around 1968 (she was about 40) when a specialist at Wycombe Hospital, Dr. Lord, recognized in a set of X-rays that she had three kidneys! And they had become tangled up inside her. That took four hours of surgery to fix, and Dr. Lord removed several pounds of waste products that had accumulated because of the knots. Until this happened, dad used to tease mum about the third child that she appeared to be carrying! The operation stopped that particular tease!

Apparently unrelated symptoms proliferated over the years, until mum was sent to see a specialist at Bart’s Hospital in London, Doctor (later Professor) Michael Besser. He was an endocrinologist, on his way to becoming an eminent endocrinologist, and diagnosed her as having Cushing’s Syndrome, among other related illnesses.

I don’t remember when she started seeing Besser, as he was known around the house, in the late 1970s I think (she was around 50), or when he diagnosed her wide-ranging collection of ailments, but during her later years he asked her to come to classes that he taught at Bart’s on her illness(es) so that she could be introduced (shown) to students. She was not entirely comfortable being used as an example, and felt like a bit of a freak, but normally attended as requested.

No-one asks a hypochondriac to serve as a teaching specimem! And in retrospect I find it hard to understand why I ever doubted mum’s own reports of her health, but I did. We all did, even her local doctors.

There was perhaps something in our incapacity to help which turned us against her, at least on that level.

Living on steroids, as she did for 20 years or so, did not help her emotional life either, or make it easier for her family. I remember her berating me vigorously for not calling or visiting often enough. And this was when we lived in Paris, and I was visiting her every four or six weeks, sometimes with grandchildren! Which felt like I was doing my bit, but not for her.

She had lived alone since dad died in 1983.

Sue’s and mum’s relationship had become increasingly problematic since dad, the peacemaker, had died. Sue and her family had moved to California in 1987, the year that I moved from New York to Paris, and her visits to England became a source of great stress for both mother and daughter.

Sue dreaded her mum’s reproaches, which were frequent, and at times took the extreme step of not visiting her mum during one of her trips to England. Mum would always find out, of course, and was deeply hurt, not forgetting infuriated, each time that happened. Her reproaches became more ardent, and Sue again sought to avoid them. A vicious circle, which neither won.

Of course, mum was a lonely widow at the end. But not as lonely as she could have been. I was close enough to visit regularly, as were others in the extended family. Sue did visit from California: in fact, she was staying in mum’s house the week that she died, arriving after I had left to go back to Paris.

Since her husband had died, 13 years before, mum had been adamant with us that dad had never strayed. But he had; we all knew it.

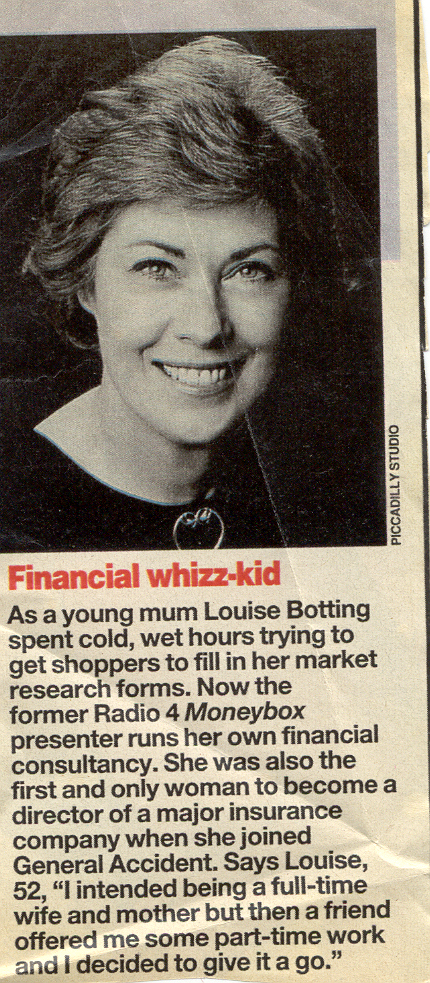

I doubt that he had strayed with Ms Botting, despite her obvious charm, because he had worked with her.

Rather, I suspect that the clipping was mum’s reminder to herself of the downside when she caught herself missing dad too much.

And mum still had a lot of friends, both locally in Marlow and further afield. Dad had left her with the means to visit family and friends herself even when she couldn’t drive any longer or even take the train. 150 miles each way in her favorite taxi was quite a feat! She maintained occasional trips like that almost until the end.

Each life’s emotional issues build up over time, more in sickness than in health. This is not the place to go into more of our various accumulated family issues: they would take too long to elaborate, and most of them have evaporated in the years since mum died. I no longer remember much in the way of specifics. Better to leave sleeping dogs lie.

Both Sue and I, and our respective families, were close enough to mum by the end. Somehow, what we had shared when we were all younger, healthier and less grating on each other, had been enough to weather the increasingly frequent storms. I’m very grateful for that, and hope to reproduce it with my own children.

Mum herself, who had been warned by the doctors that her end was nigh, was telling everyone who would listen that she had lived a “complete life,” that was the phrase, and had no regrets.

Even at the end, she was focusing on the rest of us, because everyone who knew that she felt that way felt better because of that knowledge.

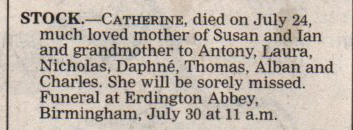

The funeral was held on July 30, Nick’s 10th birthday, in Erdington Abbey on the outskirts of Birmingham. Her mum and dad were buried there, near where they had lived and died, and she had provided in her Will that she would join them.

It was only when cousin Andrew Whitton drove his mother Margaret, mum’s oldest sister, away from the church right after the service, with no time to spend with any of us, that I realized that there was perhaps a problem with this arrangement.

Indeed, it turned out that there was not enough space remaining in the grave for all of mum’s siblings, and that all had not agreed with mum’s choice, although she thought that they had.

Typical! And typical of mum, the youngest sibling, to take advantage of her oldest sister by dying before her!

The priest spent several minutes during the service trying to explain why mum’s prolonged suffering did not suggest that there is no God: no-one had told him that any of us were looking at things that way.

As he elaborated, I remembered Arthur Leff, my contracts professor in law school, explaining that an “Act of God” was something that no reasonable God would do!

The name on the back of the photo, in mum’s writing, is John E. Broughton.

Another of mum’s coffee table photos, perhaps the most striking. I don’t remember ever seeing the photo, which must date from the war (WWII). That was when mum was single and in the ATS (the UK’s women’s army), from mid – 1944 until 1947 or ’48. She met dad not long after being demobbed, and they were married in 1949.

So she remembered her single life too, those years sitting all alone on the sofa.

I was delighted.

The real problem, when you get down to it, is that everyone dies, even your mum. And you can’t do anything about that.

Sue and I both shared with mum a taste for Kris Kristofferson, and we picked one of his songs to be played in the Abbey during the funeral service. We gave them a cassette of “Border Lord,” the album with the song on it: which was the last we saw of that cassette!

Here’s the first half of the song. The words alone will give you some idea of what we were feeling. I like to imagine that the river in the song was the Thames, flowing through Marlow, and that mum was there, sitting on the riverbank on a summer’s day in Higginson Park, with her skirt pulled up to her knees and her toes dipped in the cool water, when she died.

I never had no regrets, boys; not for nothing I’ve done.

I owed the devil some debts, boys, paid them all up but one.

And I don’t even regret the living that I’ll be leaving behind.

I’ve gotten weary of searching for something I couldn’t find.

I’m going down to the shade by the river one more time,

And feel the breeze on my face before I die.

I’m gonna leave whatever’s left of my luck to the losers,

Then bend me down and kiss the world goodbye.

© Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

We went back to the land of the living as soon as the funeral was over.

In a former quaker factory town called Bournville, across Birmingham from the graveyard, is the original Cadbury factory, the site of my first memorable school excursion back in about 1962. Haslucks Green County Primary School took its pupils on a tour of a working chocolate factory!

It was Nick’s birthday, he was very sad about his grandmother dying, and the Cadbury factory had become Cadbury World, a theme park built around chocolate.

If you have to bury your mum, your grandma, what better place than a city with a theme park based on chocolate? And the children agreed!