(written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and performed by the Beatles)

Rock’n’roll was living like a rolling stone in the proverb taught by Bogbrush in his English class at Solihull School, gathering no moss.

It was Bob Dylan singing “Like a Rolling Stone:” “How does it feel to be on your own, with no direction home, like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone?” Yep, that’s how it feels, Bob, like a complete unknown. (Written and performed by Bob Dylan)

Rock’n’roll was the Rolling Stones signing that anthem of pimply adolescent boys everywhere: “I can’t get no Satisfaction. I can’t get no girl reaction. Cause I try and I try and I try and I try.” Me neither! (From “Satisfaction,” written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and performed by the Rolling Stones)

And it was Jann Wenner’s Rolling Stone, the magazine he founded in 1967. Here’s Jann, reviewing the Beatles’ White Album: “Rock and roll at once exists or doesn’t exist: that is why the term ‘rock and roll’ is the best term we have, as it means nothing and thus everything – and that is quite possibly the musical and mystical secret of the most overwhelmingly popular music the world has known.” (© Jann Wenner and Straight Arrow Publications) Oddly enough, there may be something hidden in there, but I doubt it. If Jann could have shared whatever it was that he was smoking, maybe I would doubt it less!

From Rolling Stone, long after Jimi was gone. www.rollingstone.com.

In those years, rock’n’roll was the soundtrack of a teenage life. The soundtrack was played on a transistor radio in the kitchen at home, or on a jukebox in a café or pub. It was played on a portable record player we bought in Italy one summer holiday that played only singles at 45 rpm, where similar machines seemed to be playing the Beatles everywhere on the beach. It was the BBC’s “Top of the Pops” and Pan’s people, its sexy young dancers on the TV, showcasing the top stars once a week, and disk jockeys like Tony Blackburn and Jimmy Saville playing pop every day on BBC’s Radio 1. The BBC, that bastion of cultural conservatism in my youth, surprised us all by generally encouraging this loud and edgy phenomenon. They banned “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” because of its suspicious initials. But Lennon and McCartney could have been thumbing their noses at the establishment (they did enjoy doing that!), and so that particular banning did not appear petty or mean.

I had my own edge in terms of listening to music, courtesy of David Milsom’s father. He was a pilot for the precursor company to British Airways, named the British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC. The British knew how to impress with names in those days! Captain Milson flew the Pacific routes for years, and on one of his trips to Singapore, I think it was, was kind enough to buy for me (with my money, saved from earnings at the White Swan) and bring back with him to England a duty-free Sanyo radio-cassette player. Before the era of personal music players, Sony’s brilliant Walkman and Apple’s equally brilliant iPod, I used to walk down Marlow High Street with that radio cassette player cradled in my arms, belting out through its loudspeaker our favorite songs of the moment. If anyone complained about the noise, I would turn it down, but people rarely did, because I was past them before they knew where the noise was coming from. I took that heavy Sanyo on the road with me, and slept with it under my pillow so that it would not get stolen. Choosing my prerecorded cassettes was a sensitive task, and preserving them from the almost inevitable tangling of tape was a constant preoccupation. It was worth it: I was never obliged to leave the music behind.

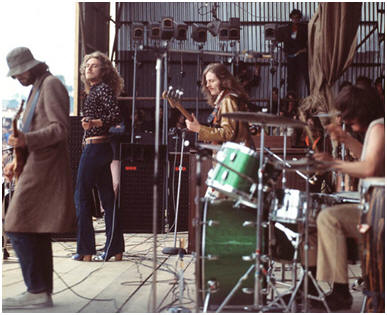

The fold-out cover of Led Zeppelin’s second album, released in October 1969. Blues became heavy metal before the phrase was even used.

Of course, with the music so important, I did buy an acoustic guitar at one point, and loved the sound it made. I sat on the bed in my bedroom strumming here and there, looking for pleasant sounds, for perhaps three hours in total, spread over a couple of weeks. I just did not have the patience to learn even simple chords. It sat in my closet at home until I sold it a couple of years later. I sold so many of my best toys and playthings: what a waste! I never regretted selling the guitar, though: great uncle Alfred Stock may have been an organist, composer and member of the Worshipful Company of Musicians, but that gene did not reach me!

If we couldn’t play it, we could certainly talk about it. We spent hour after hour talking about our rock’n’roll heroes, sharing news and stories about them, and we were particularly fond of expressing strong opinions on musical topics about which we knew little or nothing. I distinctly remember a completely bullshit discussion in the Ship, for a time our favorite haunt and a pub in Marlow, on whether Eric Clapton’s guitar-playing technique could be improved upon. We called him “clapped out,” with impressive lack of judgment. There was cigarette smoke everywhere, and both of us in the discussion were half drunk young men gesturing with our pints, loudly sure about everything we said. I knew nothing about Clapton’s technique, of course, and I’m pretty sure that the fellow I was talking with knew about the same. But that was the dialog. We were going to act as if we knew it all: that was our age. But what we knew it all about was rock’n’roll.

Rock’n’roll was in many ways the point of it all for us in the late sixties. Religion was quaint and archaic, dimly perceived as a diversion, a dream. Schoolwork was detached from our daily reality, interesting in a way but lacking any real goal. Rock’n’roll was a way out of the overly intellectual approach to life which was a natural consequence of English education in a single sex school. I listened constantly, mulling the lyrics over and relating them to what I knew and wanted, and heard the melodies playing in my head over and over again. English academic education was very good, but it was John Lennon and Bob Dylan who first taught me emotionally about poetry. I had enjoyed the teacher’s explanations of classic Shakespeare speeches, like Marc Antony burying Julius Caesar, but they did not get close to playing on my heartstrings the way that songs like “Girl” or “Blowin’ in the Wind” did. “She’s the kind of girl you want so much it makes you sorry. Still, you don’t regret a single day” (from “Girl,” written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney and performed by the Beatles). Not that I really understood it, but it felt like something was moving inside me.

The Nag’s Head, yer basic pub, with yer basic blues. This photo is from a modern advertisement for the pub, which appears to have changed little: perhaps cleaner than it was, with newer paint.

Political consciousness was in the air among us, especially after the French students and workers seemed to ally themselves in May 1968. But what motivated them and what they were seeking was unclear, and I didn’t like the idea of revolution either. The French revolution had been a bloody and disgusting mess. Ditto the Russian revolution: even more bloody, if anything. Things did feel wrong socially in England. It was more visible in Birmingham than in Marlow, which had some of the immunity of a dormitory suburb, but many lived lives that were miserable. The Indians and Pakistanis who had moved there to improve their lot were going through poverty, racism and their own kind of torture. The men who ran the country seemed benign more than malignant, but the consequences of their rule seemed less benign. Even in Marlow, school was hopeless. John Lennon’s point of view in “Revolution,” one of the world’s best ever “B” sides of a single, was from a social perspective pretty close to dead right. We did all want to change the world, but how was harder to address. So we didn’t really try. We were grateful to have a rationale for not doing so, and we carried on with what felt important, rock’n’roll.

Our music was incredible. It wasn’t ours in the sense that we made it, but it was ours in the sense that it happened for us, for my generation, at our time. We adopted it, in many cases despite ourselves. It had taken me a while to accept the Beatles when they came along. Likewise with hard rock. The Who gave me easy access to more electric music, celebrating “MY Generation.” Adrian made the introduction that I remember the best, in the form of Led Zeppelin II. He kept playing it so LOUD: “way down inside, woman you need . . . LOVE!” (from “Whole Lotta Love,” written by Robert Plant with an acknowledgment to Willie Dixon, and performed by Led Zeppelin). I tried to get him to turn it down, but he wouldn’t, and I learned to mute my instinctive recoil from both that noise and the obvious vulgarity. The vulgarity bothered me as much as the noise. It was partly my inherent conservatism, and partly my boarding school distaste for boys being boys. Looking back over forty years, from when Jimmy Page is invited to play the Olympic Games and “Stairway to Heaven” is regularly voted one of the top ten rock’n’roll songs ever, you cannot imagine how radical and avant-garde and just plain loud that band was then. “Gonna be your back door man!” I wasn’t sure that I understood precisely what they meant, but I was sure that it was really disgusting. I did get the heavy metal style eventually, but it took quite a while.

Listening to the music and talking about it was our daily life. Then there were the concerts, our excursions into the heart of the beast. A club called the Blue’s Loft opened in a pub called the Nag’s Head in Wycombe, the next town across the hills from Marlow. The blues bands and aspiring rock’n’roll bands came to the Loft week in, week out, and as we learned about them we started going. Not a whole lot, but it was local enough to thumb to before the Mini arrived and close enough to pay the petrol for after. It stank, of stale beer and urine. Everybody smoked cigarette after cigarette, and maybe a joint or two across the London Road in the park. Mott the Hoople played there regularly before anyone had ever heard of them, Jethro Tull played one set before launching themselves into the stratosphere, but the real band there week in week out was Brewer’s Droop. Nobody ever heard of them later on, they never made it big like some of the others, but they were the house band and their name was irresistible. The brewer’s droop was the brewer’s drooping and beer-filled gut!

The Grosvenor House Hotel, seen from Hyde Park in a 2007 publicity photo. Why England still had class.

More distant concerts remain a bit confused. One summer, the Rolling Stones gave a free concert in Hyde Park in London. I do not remember actually seeing them, although I do remember hearing King Crimson performing “In the Court of the Crimson King,” and the internet confirms that King Crimson played that concert before the Stones. That marvelous song was the “wow” moment for me. But the Stones were the stars, giving a free concert in remembrance of Brian Jones, a deceased Stone, one of rock and roll’s first casualties. I later learned that he died after having been kicked out of the band for drug abuse. Think about that one for a moment: Brian Jones must have been a complete berserker if his wild-man band mates kicked him out for drug abuse! His survivors gave a free concert to several hundred thousand adoring fans in London’s Hyde Park. Adrian tells me that we actually did watch the Stones perform. Maybe. Maybe not.

I remember the oddest fragments of that rare and crazy day. Which is probably a good thing. We were thirsty much of the time, and at some point during that interminable and hot afternoon decided to ask for a glass of water in a hotel on Park Lane, the Grosvenor House Hotel. Park Lane, which runs down the east side of Hyde Park, houses some beautiful and luxurious hotels. The Grosvenor House was one of the most luxurious, a full five stars. Here we were, me in my dark blue crushed velvet Kings Road pants with my dirty stringy hair, a pale shadow next to Adrian and his light blue crushed velvet cape, and a yellow headband tied around his long golden blond hair. In we waltzed, with the confidence of the totally high, up to the Reception Desk and asked for a glass of water, please. I did the asking: Adr. was taken aback, perhaps by our own sheer gall. Even though I remembered the “please,” I fully expected to be told in no uncertain terms to get out. It was an august establishment, and we looked like something the cat had dragged in, and a crazed cat at that.

The Grateful Dead at the Hollywood Festival, near Newcastle-under-Lyme. Needless to say, the view of the band for most of us in the audience was not quite as good! From www.ukrockfestivals.com

Nothing of the sort. There was a short pause for breath on the other side of the counter, but we were immediately referred to the Restaurant. “It is actually closed now, sir.” He definitely said “sir:” I felt it reverberate around my head. “But I’m sure that the Maitre d’ will help you.” Upon seeing us in the entryway, the Maitre d’ duly scuttled over from where he was working at the back of the deserted restaurant, enquired after our needs as if he was addressing royalty, sat us down at a table near the door, and personally brought us a tray with a jug and two glasses of iced water on. Rarely have I been so proud to be English. When I discussed it with dad later, omitting some of the detail but he knew how Adrian and I looked, he said that the Hotel was duty-bound under English law to offer water to all travelers. That’s as maybe, but there is no way that any law obliged the people who looked after us there to be so polite and kind in the face of such adolescent provocation. That was character. That was training. That was the plus side of being English.

I clearly remember regretting in the Mini on our way home that we had not even glimpsed the Stones’ act, but nothing like as much as I regretted how we were driving the car. I was leaning over from the passenger seat moving the pedals with my hands, a very difficult maneuver in an Austin Mini, and Adrian was changing gear and steering in the driver’s seat. He had not yet learned to drive, which was the problem that prompted our regrettable solution. If we had been doing this in a field out in the country somewhere, we would have been less stupid, but we were doing it on our way home, which unfortunately took us on the principal road west out of London. Our passengers put an end to that stunt relatively quickly, if I remember correctly.

This was pretty much our view of the stage at the Hollywood Festival, from the crowd. The objects at either side are a large inflated penis and larger inflated breasts. We couldn’t see the musicians, but we could see the inflatables. Rock’n’roll! From www.ukrockfestivals.com

But I apparently remember very little correctly in this case. When I looked the concert up on the internet, it turns out that it took place in 1969, which was before I was given the Mini! The crazy drive certainly happened. The concert certainly happened, and both Adrian and I agree that we attended, on some level. But never the twain did meet! I’ve been trying to piece it together, emailing friends. They have the same problem. Everybody there has the same problem. Here’s a comment from a 2007 website report on the Hollywood Festival, the Grateful Dead’s first UK concert on May 24, 1970. We made it to that one, 27 years to the day before Marie-Hélène and I got married. “The Grateful Dead went on around 4:30 on the Sunday afternoon, after having driven up from London by coach. By no means top of the bill, but many people had come to hear them out of curiosity to see if they were all they were cracked up to be. . . . . Unfortunately , the BBC TV crew who were supposed to be filming the show were allegedly dosed on Owsleys finest [ndlr: LSD] and the footage was unusable as the cameramen were totally out of it – so we have the Dead or their followers to blame for this event not being preserved for posterity.” No, you had the drugs to blame!

Adrian finally clarified a part of the mystery. We also attended Pink Floyd’s free concert in Hyde Park, he tells me, during the summer of 1970. So that must have been the day that we drove back together in contorted positions in the front of that tiny car. I don’t remember seeing the Floyd either.

This is the key problem with elaborating my rock and roll years, referred to in that old joke about the ’70s: if you were really there, you can’t remember a thing! I have to go to my mother’s old diaries, terse at the best of times, or to the internet to remind myself about rock and roll before I turned eighteen.

This is not a real ticket. Sometimes I think that we all actually paid for tickets at this festival, but other times I doubt it. 2.5 pounds was a lot for a schoolboy, even one working part time, and even though it bought a fantastic line up.

Implied in that amnesia, even in the stereotypes of the seventies, is extensive use of recreational drugs. I did not join in that particular movement. I experimented with the best of them, and of course did partake at festive times, but was always skeptical about their benefits. Dad used to go on about the health risks, which was his way of trying to turn me away from them. In light of the tobacco health risks that he assumed every day, I could have easily dismissed that line of reasoning.

That I did not reveals something about my own reaction to recreational drugs. I used them occasionally, but felt paranoid a lot when I did, which deterred allowing the process to become a habit. Alcohol was worse on the stomach, but an easier way to lose inhibitions and let go. Plus I was scared of illegal drugs. The domino effect from the softer drugs to the harder seemed logical because a person with any kind of chemical dependency could likely evolve to another kind without much difficulty. Already, I could see that there was nothing more pathetic than someone addicted to hard drugs, and I had no desire to be pathetic. In my case, at least, the amnesia of the seventies was more linked to the excitability of a teenager at that time in his life, and the emotional churning I went through every day.

The spring and summer of 1970 was my peak rock and roll peak moment, but because of the same memory foibles I only discovered that in 2007 by surfing the internet. Over the May bank holiday weekend we went to the Hollywood Festival in Newcastle-under-Lyme, in June we went to the Bath Festival of Blues and Progressive Music, and in August we went to the Isle of Wight Festival. We did something in July, but, guess what, I can’t remember what it was. Maybe it was that Floyd concert in Hyde Park. At least three rock festivals in four months, and I don’t remember a lot of it. I didn’t even remember that all three were so close together in time. It felt like I was at rock festivals for years.

Led Zeppelin on stage at the Bath Festival of Blues and Progressive Music in June 1970. Okay, so what if they were stick figures from where I sat? This was Zeppelin live, and you don’t get more alive than that. From www.rollingstone.com.

But here is what it meant to participate as a spectator in those three festivals. In four months I saw, maybe, live in concert, Led Zeppelin, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, Black Sabbath, Free (twice), the Byrds, Jose Feliciano, the Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Country Joe, Canned Heat, Santana, Steppenwolf, Kris Kristofferson, Chicago, Procul Harum, John Sebastian, Joni Mitchell, Miles Davis, Ten Years After, Emerson Lake and Palmer, Sly and the Family Stone, Donovan (twice), Pentangle, the Moody Blues, Jethro Tull, Joan Baez, Leonard Cohen, Richie Havens, John Mayall, Johnny Winter, Tiny Tim, and a whole bunch of other bands too numerous to list. Okay, I did not necessarily see them all, but I bet I heard most of them.

Let’s put it another way. I saw Jimi Hendrix play God Save the Queen and Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Who play all of Tommy from beginning to end, the Moody Blues play Nights in White Satin, Led Zeppelin play Whole Lotta Love and Dazed and Confused, not forgetting Johnny B. Goode, Free play All Right Now, the Doors play Light My Fire, Joni Mitchell play Both Sides Now, John Sebastian play Do You Believe in Magic, the Grateful Dead play St Stephen, Country Joe scream the Fish cheer, the Jefferson Airplane play Somebody to Love, Steppenwolf play Born to be Wild for the Hells Angels, Mungo Jerry play In the Summertime, and Jose Feliciano play Hey Jude. Reading the list through now, it reads like a who’s who of classic rock. That summer, it was what we did on weekends, when we could afford it or even when we couldn’t, for fun.

We were riding a wave. Festivals had started in a less substantial way a couple of years before, but they didn’t really catch on, as it were, until that summer. We had no car until December 1969, and thus tended not to venture far afield, but of course we didn’t necessarily drive the Mini to the festivals. We drove it to Hollywood, my “first long trip” mum wrote in her diary, and dutifully had a dumb little accident on the way there. Nothing to write home about: I was backing fast down a driveway after siphoning a little petrol from a parked car and my door, which was ajar, hit a fence post.

We did not drive to Bath, because getting there was an easy thumb due west from home straight along the old A4. It took us one ride from the roundabout in Maidenhead in a van with a bunch of other hitchhikers, all going to the festival. For the Isle of Wight we drove down to approach the ferry for the island, but could not afford to take the car on the ferry. I think that foot passengers travelled free that weekend on the ferry boats. We were 17 years old, which was a good age to start spreading our wings, or to put it another way we were just ready, and we weren’t the only ones. The Hollywood Festival had an estimated 45,000 in attendance, Bath had an estimated 150,000, and the Isle of Wight remains the UK festival with the highest ever attendance, estimated at between 500 and 600,000. Now that was one hell of a wave!

The sea of humanity that was the 1970 Isle of Wight festival. This picture was taken not far from where we spent the first couple of days sitting on the hillside overlooking the enclosure. The stage was a long way away (top left), but on that hillside we still saw it and felt it. Malcolm George’s photo, on www.ukrockfestivals.com.

It crashed, of course, as waves are wont to do, as counter-cultures are wont to do, each in a wall of blinding spray. We were hundreds of thousands of hairy adolescents and post-adolescents seeking to live in peace and harmony, united by our music and little else apart from acne and body odor.

We did have a dream of sorts. Something could be done, if we all tried hard enough, were high enough, and kind enough. What could be done was unclear, and that the wave would crash was inevitable. But our generation felt entitled to go through its spiritual search for meaning. Thanks to our parents’ generation, we were free from the constraints of war and scarcity that had burdened their lives. We could and did make our own exotic culture, wherever the promoter planted the seed, and called it a rock festival.

The problems inherent in our self-made cultures were most evident at the Isle of Wight, where so many amazed me by appearing so angry despite the incredible music that played day and night. Don’t get me wrong: we had a fabulous time. But with so much going for that festival, it was distressing to see so many finding fault and then harping on it incessantly. The worst offenders were the French anarchists who congregated down the hill from where we spent the first couple of days. We had no money left for tickets, but the organizers had thoughtfully placed the entire paid enclosure at the foot of a relatively steep escarpment that was public land. Those of us without money for tickets, perhaps 150,000 of us, watched the show easily if distantly from the hillside. It was a bit too far from the stage, and off to the side, but for free seats at a paying festival, it was great. Not for the French anarchists, though. They ranted and raved that the whole thing should be free for all the people, as if it cost nothing to organize and build. They worked themselves up into a righteous rage, incomprehensible to me because their English was as hard to understand as their French, and then started battering down the flimsy fences separating those who paid from those who did not. For some reason, this festival had not engaged the Hells Angels as security: they would have known what to do with anarchists smashing things. As it was, the anarchists had a field day inflating their own importance, and related bad vibes, almost without restraint.

The Isle of Wight audience dancing near the stage. Photo from Col Underhill on www.flickr.com.

The bad vibes got to the organizers, and the announcer on stage joined in the fray. He made repeated agitated announcements over the first couple of days, trying to explain and justify the ticket prices and pointing out that the way things were going the promoters would be ruined. That made sense to me. There had been an enormous amount of preparation, and rock’n’roll musicians were obviously paid for their work. The anarchists then succeeded in convincing the organizers to surmount such common sense, and as the weekend advanced they finally announced that everyone could now get in free. In we strolled! The anarchists were gloating, the organizers sulking, and we were hungry.

The crowd at the isle of Wight showing their solidarity with the beleaguered promoters: a powerful moment for most of us. Was someone singing “Amazing Grace?” The day after the festival, Ron Foulk, one of the promoters, said: “This is the last festival. Enough is enough. It began as a beautiful dream but it has got out of control and become a monster.” www.ukrockfestivals.com.

Looking back, the stars were at times no better. Jimi Hendrix died a few weeks after his performance at the Isle of Wight. A fellow performer’s summary on the internet says that he was paralytic after that performance, and literally needed to be carried to his room in the local hotel by his entourage. Looking back, I wonder how he could have done that, drink so much and consume so many drugs that he could no longer function. How could the man who put such feeling into music, played in such a powerful and completely novel way, have treated himself so badly? He died choking on his own vomit another paralytic night, and there still has never been an electric guitarist as virtuoso as Jimi.

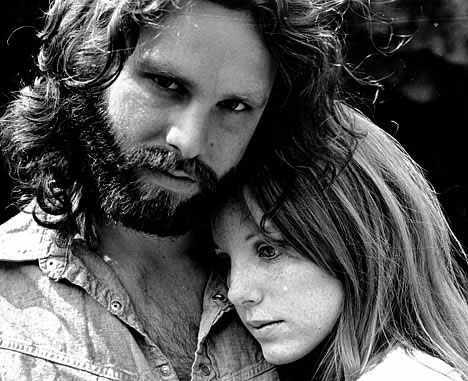

Jim Morrison died within the year, again from self-inflicted wounds. He was one of the few genuine poets of rock’n’roll, singing his poems with the Doors on the album LA Woman, the last album before he died, creating another classic testament to the enduring genius of that time in the history of rock. Here is his LA: “Driving down your freeways, midnight alleys roam, cops in cars and topless bars: never saw a woman so alone! Motel, money, murder, madness: change the mood from glad to sadness.” The beat of the song obligingly slows (from LA Woman, written by Jim Morrison and performed by the Doors). Here is a memory of an intimate relationship that didn’t work: “Cars hiss by my window like the waves down on the beach. I’ve got this girl beside me but she’s out of reach. . . . Windows started trembling with a sonic boom. Boom! A cold girl will kill you in a darkened room” (from “Cars Hiss by my Window,” written by Jim Morrison and performed by the Doors). Jim Morrison died in his bathtub before recording another album. Looking back again, it all seems such a terrible waste.

Jim Morrison of the Doors, with Pamela Coulson.

At the time, the deceased did not feel as significant, even if they were musicians. Our dead heroes posted warnings from the grave about the dangers of excess drug consumption, and they were useful warnings to hear. Their excesses seemed the prerogative of the filthy rich, or the truly talented, rather than individual failings that could have an impact on us spectators. We read about each of the dead rock stars in “Rolling Stone,” which wrote a mean epitaph and which seemed to devote its covers regularly to our dead heroes in 1970 and ’71. We regretted their untimely departures and missed them, even as their music took on a special additional meaning.

Rock festivals and dead rock stars taught us that nothing could change the basic fact that we and they were still people, with our own needs, which we make so paramount, and our silly desires to distinguish ourselves from others rather than find kinship with them. Rock Festival or not, we were still people. Always would be. Same feelings, for the same petty, silly reasons as in normal life. The festivals were one of the most visible expressions of our youthful romanticism, and dumb anarchists or lousy bathroom facilities ruined their ambience. Rock stars were our heroes, but they let us down by dying so stupidly or feuding among themselves like the latter-day Beatles. We had bad trips or lived through social diseases or obsessed about how lonely we felt. I hung on to the desire to improve upon our nasty and intolerant forefathers for quite a few years, but on some level gave up inside after that rock festival summer of 1970. There were bound to be limits on what even we could accomplish. John Lennon had us down, the way he had a lot of things down: “Keep you doped with religion and sex and TV, and you think you’re so clever and classless and free, but you’re still fuckin’ peasants as far as I can see. . . . “. (From “Working Class Hero,” written by John Lennon and performed by John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band).

What remained of rock and roll after that awesome wave rolled in and crashed into a wall of blinding spray? Well, apart from a mildly broken utopian fantasy, not a lot ever changed. The music never died.

The amazing “Pinball Wizard” is a part of the Who’s rock opera “Tommy.” “Ever since I was a young boy I’ve played the silver ball, from Soho down to Brighton I must have played them all. . .”. Written by Pete Townsend, and performed by the Who. Before there were video games, there was pinball. We played constantly in 1969 and 1970, at least until I left Borlase’s.

Rock’n’roll was the Who playing their rock opera Tommy from beginning to end late on an August night at the Isle of Wight: “Tommy, can you hear me?” they sang. Not all the time, no. The music welled up and faded back out on our hillside, giving us tantalizing phrases and catchy melodies that came and went with the night’s breeze. “See me, feel me, touch me, heal me . . .“. We tried to see them and hear them and feel them from too far away, stretching to grasp the new songs. “Right behind you I see the millions, on you I see the glory.” Where had the phrases come from? Were they written right there? Were we the millions on the hillside? Of course not. Yet in a way, maybe we were. The melodies wafted around us, tantalizing. “From you I get opinions, from you I get the story.” Not from us, not yet. That would come later. But even with the melodies floating up and down the hillside and the phrases almost scrambled, we felt something so special and real. “From you, I get the story. ” (Extracts from “We’re not Going to Take it,” written by Pete Townsend and performed by the Who).

Rock’n’roll was David Milsom dancing to Mungo Jerry’s skiffle sound at the Hollywood Festival, waving his arms in the air, throwing his head back and looking up at the sky, laughing out loud as he threw his body wildly around. It was sunny, with those bright white fleecy clouds of springtime in England scudding across the horizon. We were in a natural amphitheatre somewhere near Newcastle-under-Lyme, and hadn’t paid a penny to watch. “In the summertime when the weather is high you can chase right up and touch the sky . . .” (from “In the Summertime,” written by Ray Dorset and performed by Mungo Jerry), sang the band with a smile in the melody and another built in to the skiffle. Normally a mellow fellow, living a life of enforced constraints in the boarding house at Borlase’s, David was not given to wild dancing or effusive public displays of emotion. I looked across at him with amazement as he gyrated back and forth in the middle of the crowd on that sunny hillside: what a feeling!

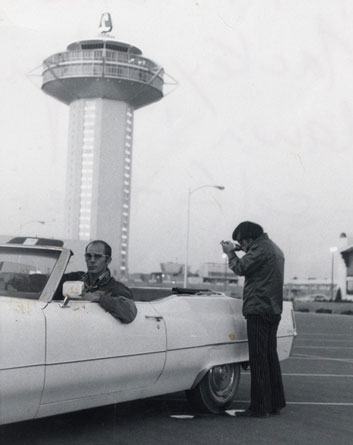

Hunter Thompson in around 1970 in what looks like a Cadillac convertible. Was this taken in Las Vegas? Copyright 2007 the Estate of Hunter S. Thompson / The Gonzo Trust/ Courtesy of AmmoBooks.com.

Rock’n’roll was Adrian beaming and gesticulating, excited by the discovery of a new song, this one from Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. “What’s the ugliest part of your body? What’s the ugliest part of your body?” He was almost dancing, grinning widely, close to spitting his enthusiasm as he punctuated the lyrics by pointing at me again and again. “Some say your nose, some say your toes, but I think it’s your MIND!!” Speak for yourself, Adr! (From “The Ugliest Part of Your Body,” written and performed by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention).

Another time, after I returned from the US, he started yelling at me: “The American army, the American army, wait till the Russians get hold of you! Not forgetting the Navy, not forgetting the navy, and the Air Force too!” That sounds like an English band, but I couldn’t find the lyrics on Google. Maybe Adrian invented them: he was very close to rock’n’roll for a few years there.

Rock’n’roll was the Release tent at festivals for people on bad trips, as in LSD. Release was one of the spontaneous associations that appeared almost out of nowhere at the time, with the goal of helping those hurt by illegal drugs. I volunteered in the tent a couple of times to help talk people down from bad trips and reassure them. Fearing that I would intellectualize some poor tripper into total torment, I’m not sure that I accomplished much. “You see bats, you say? Wheeling around behind the tapestries and screaming? Well let’s think about that for a second. Do bats scream? Is it likely that in the middle of the day they would have found their way into this tent?” I would not have helped a lot. But the effort of the Release organizers that went into the calm and the comfort of the atmosphere was itself very reassuring. The music played on outside that thin layer of canvas, people walked by chatting, but inside was an island of calm with Indian tapestries and cloths in saffron colors dividing the tent into cozy and comforting enclaves with cushions spread around to lie on, tissues for tears and someone for anyone troubled by drugs to talk with.

The cover of Crosby Stills & Nash’s first album. Whoever would have thought that they would one day have their own star on Hollywood Boulevard?

Rock’n’roll was Hunter S. Thompson inventing gonzo journalism with his Samoan attorney “somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.” His extraordinary article “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” which began with those lines, appeared in Rolling Stone in 1971, long before it ever became the book or the film. I read the whole long article across two issues of the magazine. Hunter was glorifying the consumption of a cocktail of illegal drugs in quantities that should have killed him, all the while attending a District Attorney’s convention on illegal drugs in Las Vegas. It was funny, it was wild, but ultimately it was disturbing. He himself was a close cousin to the pushers he put down in the article.

Rock’n’roll was any issue of Rolling Stone. Here are parts of one selected almost at random and dated July 26, 1969: a long and patient interview with Jim Morrison, ending with one of his poems and including comments of his like “We have fun, the cops have fun, the kids have fun. It’s kind of a weird triangle;” fabulous photos illustrating an article on Buddy Guy, the long-lasting Chicago bluesman; ads for the new Joni Mitchell album, “Clouds,” and the new Johnny Cash album, featuring “A Boy named Sue (a fantasy);” an article on the Tibetan Book of the Dead and another on a lawsuit between the Grateful Dead and the owner of studio they had used; and record reviews of the first Crosby Stills and Nash album (“an eminently playable record”) and Captain Beefheart’s “Trout Mask Replica,” (“a stunning success”). This was my world.

Rock’n’roll was still a new way of living, still an adolescent dream and still a parental nightmare. The two were not unrelated! It was a challenge to some established order, and an attempt at establishing a different order. It was flawed, as we were flawed, as people are flawed. But however the festivals failed to live up to their utopian expectations, and however many of our idols killed themselves, it never felt as much of a failure as my parents’ generation felt to us, not even close. For all its faults, rock’n’roll was so full of meaning at the precise time when meaning was so hard to find or grasp or believe in anywhere. Rock’n’roll was the closest thing we had to the spritual. I didn’t know it then: I didn’t understand what spiritual meant. But listening to music was the closest thing I had to what I had looked for in a church, the closest thing to our collective soul.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 23 “America”

Previous chapter: Chapter 21 The Working Life

If I Only Knew: Table of Contents