My mother left us all on July 24, 1996, but not before giving our entire new family a rousing welcome and wonderful support.

At the Randolph Hotel in Oxford (UK), this was the first time that grandma met Marie-Hélène, Daphné and Alban. It was the summer of 1994. She had already gone through years and years of debilitating illness, but could still throw you a winning smile.

Grandma took my new blended family to heart, all of it. Something had gone wrong between her and Sunshine years before; I never did figure out what. But her satisfaction that Sunshine’s and my relationship had come to an end was far from the only reason that she was so enthusiastic about the new us.

Daphné and Alban in the Randolph during the same visit with grandma. Daphné learned how to say the word in English in double quick time!

I think that she saw Marie-Hélène as the kind of woman she had always wanted me to be with. She never said as much, but she was very attuned to class, in the English sense of the term. Marie-Hélène was loaded with class.

In any event, missus did all that she could to help with our blending and ease our way forward. The annual passports to Disneyland, which she gave us two years running, were perhaps the most valuable of her gifts in terms of the enjoyment they produced for all of us. But there was regular help with journeys to England to visit, help with refurnishing Le Tahu when half the furniture left with Sunshine, and of course constant presents for all of the children.

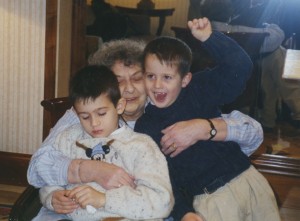

Taken just after New Year’s in 1995. Look at all that motion and feeling, in just two small boys! It was quite a job being a grandma for all that movement, especially as her illnesses worsened and she tired more easily.

I have to admit that this period of maternal support was deeply meaningful for me. Because I had left England when still a teenager, attended college and law school in the US and not had a child until 1986, I had missed out on parental support compared with my sister Sue. I paid for all my college and law school myself, for example. Sue stayed in England until 1987, long after dad died, and had her children in 1975 and 1977. Naturally enough, when they were born she got all the help that she could have wanted: down-payment on a flat and then a townhouse, with all new furniture throughout. Something like that only happened to me in France, beginning 15 years later. I finally felt treated equally.

With her best friend Kay and her surprise birthday cake on her birthday in 1995. Goofy delivered the cake at the California Grill in Disneyland Paris! That was the last time that she made it to Disneyland herself: she wasn’t up to it after that.

In light of her English prejudices (which never entirely fit because she was of working class Irish extraction!), we were all doubly grateful that she took so warmly to Marie-Hélène and her children. Of course, all three are very lovable, but prejudice can blast right through the finer characteristics of those discriminated against if it has a mind to. In this case, it did not. We only had two years together as a family before she passed away, but no-one was kinder or more supportive, to all of us.

We should mention her cigarettes. They were eternally present, as much so as the cups of tea and coffee which they frequently accompanied. She shared her “fags” (this was in England!) with Marie-Hélène and me (we both smoked until early 1998). After leaving the army in 1948, she smoked a couple of packs a day of unfiltered cigarettes for her entire life, and none of her ailments could convince her to quit. “I have few enough vices!” she would say. And oddly enough, the smoking did not seem to play a role in her extravagant and diverse illnesses. To be fair, almost everybody smoked in England through the 1950s, 60s and 70s. She carried on as the rest of the country quit the habit.

With me, Nick and Tom in Windsor on New Year’s Day, 1995. She could still put up with the racket and the constant motion, as long as it was in small doses! I think that she’s gritting her teeth here! Marie-Hélène took this one.

The smoking did play a role in her and Sue’s conflicts later in her life. Understandably, once we all learned about the harmful side effects of second-hand smoke, Sue did not want her children exposed to it, even when they visited their grandma. I always smoked outside as soon as Sue started asking me to, but that wasn’t really an option for mum; she was simply too old and sick. So that issue too remained in the mother-daughter air.

As I said, she didn’t last long. She was buried next to her parents and near where she was born, at Erdington Abbey in industrial Birmingham. The cemetery is between a railroad line and a major road, across from a car dealership and only a few miles from the largest Motorway junction in England. Villa Park, home of Aston Villa Football Club, where her father had a painting contract, is a couple of miles away in Aston.

RIP. I added a remembrance of dad, because his little card (barely larger than a business card) at Chilterns Crematorium did not seem enough somehow. Unfortunately, someone in the family understood that he was actually buried there! I don’t know how that happened: didn’t everyone in the family know that he’d been cremated? Most of them were at his cremation.

I remember the service, the Kris Kristofferson song that we had them play, “Kiss the World Goodbye,” mum loved Kristofferson, and that song fit, and the priest trying to explain or justify the years of illness and pain that mum had lived through. He’d set himself a hard task there. I remember Nick crying – he loved his grandma, and she was buried on his seventh birthday – and us taking the children to Cadburyland after the service, to clear their heads, and ours.

In short, we didn’t spend much time after the burial with other guests. It wasn’t like dad’s cremation in any event; mum had lived alone and sick for too long, and there weren’t a lot of people there. The burial itself caused a stir among her two surviving siblings, because it only left one space in the family grave in Erdington Abbey. Mum had told me that she’d arranged this with her sisters, but apparently they disagreed. Well, at least one of them disagreed: Andrew Whitton drove his mother, Aunty Margaret, away from the Abbey right after the service. She barely spoke to anyone there. Sad to say, that was typical Smith sibling behavior!