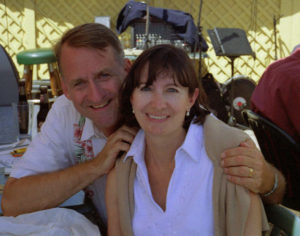

Looking back, my favorite photo of just the two of us is this one.

The obvious question is why this one is my favorite. You can barely see our faces, and the background house is not exactly a good frame. The bottle of sparkling water and my old Nikon distract the viewer.

On a Capitola terrace for Mother’s Day, 2004. The children romped on the beach and we had a bit of a tipple!

Well, for me it’s our evident complicity here. It’s an honest candid at a good time. We had our six children, aged 1 to 13, and had settled into Santa Cruz. I had found a good job at Wilson Sonsini in Palo Alto, and we had succeeded in convincing the French courts to move Nick and Tom back in with us, making the family whole again. We hadn’t gotten the furniture back yet from the crooked French moving company, but even that was moving perceptibly forward.

Wait a minute: no need for the historical analysis. It’s the complicity. Most photos of us were posed and more or less self-conscious. This one was at a school barbecue with the children running around safely in a throng of attentive teachers and parents, while we chatted away in front of a friend with a good eye for the moment. She caught the complicity that we shared so much.

We certainly needed to be on the same page. The key word in the title of this post is “minority.” There are six children, and two parents.

Circumstances required that we remained zen as much as possible. This was taken in July 2005 during the annual visit of Faby and Jean and their now four children. With ten children in or around the house, Marie-Hélène did pretty well at zen. Me, well . . .

When the children were all under eleven or twelve years old, we had some chance of imposing our view of the world in an unambiguous manner.

But the older our adolescents got, the more they realized that they could dispute and question our authority. And they did, in spades, for as long as they remained teenagers. As a rough estimate, I’d say that they remain teenagers from about 12 through about 25!

At first, our complicity triumphed over these budding teenagers, but it was hard work, and we had a lot to do, each of us. And our resources were not unlimited. That’s why many no longer have large families, because it’s financially very difficult if you don’t earn enough. We didn’t talk that through when we started out, with four children between us already. I have to admit that I didn’t even think it through really; if I thought anything, it was that I would surely earn enough. Don’t get me wrong: I did okay. But cars for almost all of them followed two or three computers for all of them, not to speak of incessant smartphones for all at increasingly absurd prices, and over time it all added up.

A bise at the bottom of the stairs at La Grée, grand-père Berhaut’s cottage in Brittany, during our 2004 summer vacation. Back in the day, la Grée was very good for us as a couple.

So the importance of the complicity was not just for us, keeping us comfortable, although as it waned in later years we could see how uncomfortable the lack of complicity in the couple. The importance was in keeping the children in line.

Fortunately, we both seemed to have similar goals for the children, to love them and to let them know that they were loved, but not at the cost of overzealous parenting or holding them back.

That worked, for a long time, even after we separated. One or two had real crises and needed serious long-term attention and support, but we didn’t let those needs trump what we knew would be the best for them in the long term. No parents do everything right, but we didn’t do badly, especially considering the complexities of having three pairs of children each with different parents. Think about it: we did, constantly!

Another bise near La Grée! A Coëtquidan, juste avant l’arrivée de Charles en juillet 1995. Son Oncle Denis est ancien élève de l’école de St. Cyr.

The older children were very careful about their respective parents. None of them wanted to be disloyal to his or her absent parent, Marie-Hélène’s and my respective exes. They each carefully called us the “parents” when referring to the two of us. It was a shorthand way of avoiding the inaccuracy of calling us mum and dad, when we are, respectively, the mum of only two out of four and the dad of only two out of four. But we were their parents, day to day and year after year.

I appreciated the formula.

Vacations were often the best times. The children were always gratifyingly self-sufficient at La Grée. We (the parents) spent more time with each other there than anywhere else, and not surprisingly kept returning for more. Even as our relationship deteriorated in its later years, our best moments together (among which July 2006 deserves special mention) were spent at La Grée.

In the grounds of the Carmel Mission, one of the most beautiful, on Marie-Hélène’s birthday in 2001.

Here’s a great joke on the topic of who’s in charge in a family. Fred has been happily married for 30 odd years, and his best friend Bill, who has been less successful in the marital stakes, asks him one day how Fred and his better half arranged things between themselves to make things work out for so long. “Oh, that’s easy,” replied Fred, “we allocated responsibilities so that each of us knew when he or she was in charge. That way, we did not need to fight about particular decisions.”

“Very clever,” nodded Bill, appreciatively. “And just how did you allocate responsibilities between you?”

“Well,” said Fred, reflectively rubbing his chin, “it’s quite simple really. She handles the day-to-day decisions, and I handle the major life-changing decisions.”

In an English pub near Banbury during our summer holiday in 2007. My cousin Ron Warrington took this one.

“And how many life-changing decisions have you made,” asked Fred.

“None yet.”

* * *

Me neither! Although I greatly appreciated a couple of the life-changing decisions that Marie-Hélène made for us, in particular the decisions to have our own children, Charlie and Alex, and to come and live in California.

It was all good, as our surf city adolescents repeated time and again. All good. But it wasn’t, of course, in the end, not our couple. I don’t really have any idea what went wrong or why it went so wrong. Shit happens, and it happened for us.

Please excuse us while we catch up on our sleep, an unending battle, at least until about 2003! This one was taken in the air on the way to Florida, summer 2000.

By the time we separated in 2010, we had each been parents for 23-24 years, 16 of those years together. With Alex then twelve years old and Charlie fourteen, we had several more years “on the job” to look forward to.

They too were great, those follow-on years, the children always changing, always engaging, but it has not been the same. Our beautiful blended family is no more. That’s our fault, not the children’s.

* * *

Click here for photos of Marie-Hélène and here for photos of me. Here for more of Marie-Hélène, and here for more of me.

Here we are at a party organized by Marie-Hélène for me, on the occasion of my 50th birthday, and here is the subject of one of our regrettable differences of opinion!