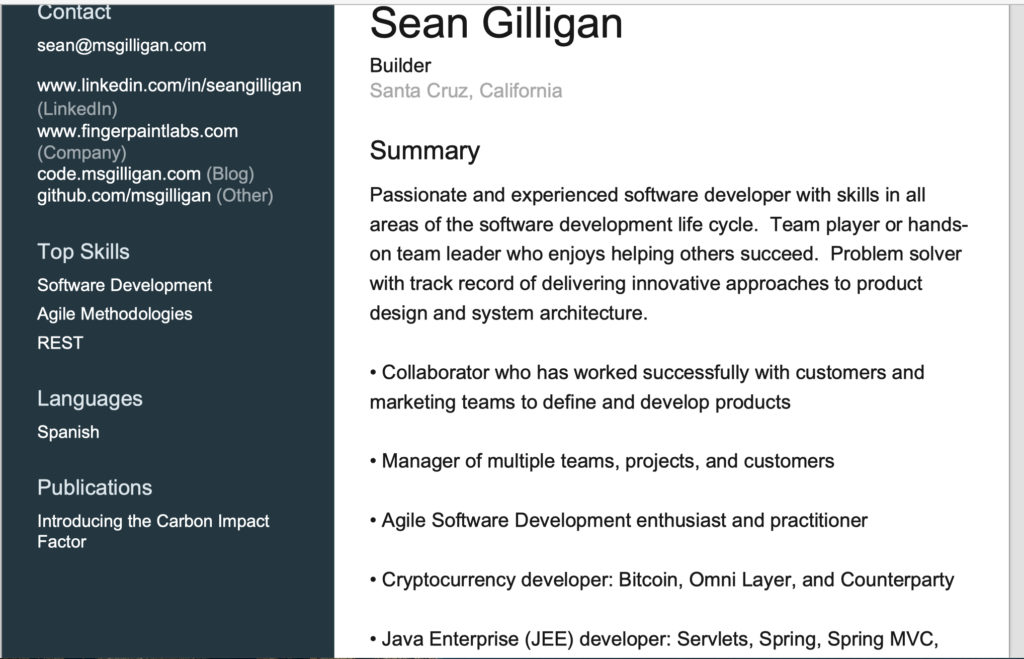

Sean Gilligan is a “crypto bro.” A software engineer, he has been evangelizing crypto-currencies and the blockchains they inhabit since 2013, and investing in crypto for as long.

He has also been sanctioned twice by his divorce court for manipulating and lying about his and his ex-wife’s assets, principally crypto, first in October 2021 for $3,500, and then in October 2022 for $30,000. The latter amount reflected the court’s increasing frustration with the costs of Sean’s constantly changing crypto stories.

How crypto works, and why it has not worked in this divorce, explains those sanctions. That is the principal subject of this post.

Crypto has enabled Sean to protract and muddy the simple questions addressed in separating community assets, which are those built up during the marriage: how much is there, and where is it?

And divorce law is simple: the couple splits community assets 50/50, with community assets being all those acquired during the marriage (except by inheritance). All of Sean’s cryptocurrency was acquired since 2009, when cryptocurrency was invented, and the couple married in 2000.

For well over three years, he has spent a great deal of money on lawyers (he’s on his third now) prolonging the disclosure process and seeking to retain almost all of the cryptocurrency belonging to this community by the simple expedient of hiding it from the court.

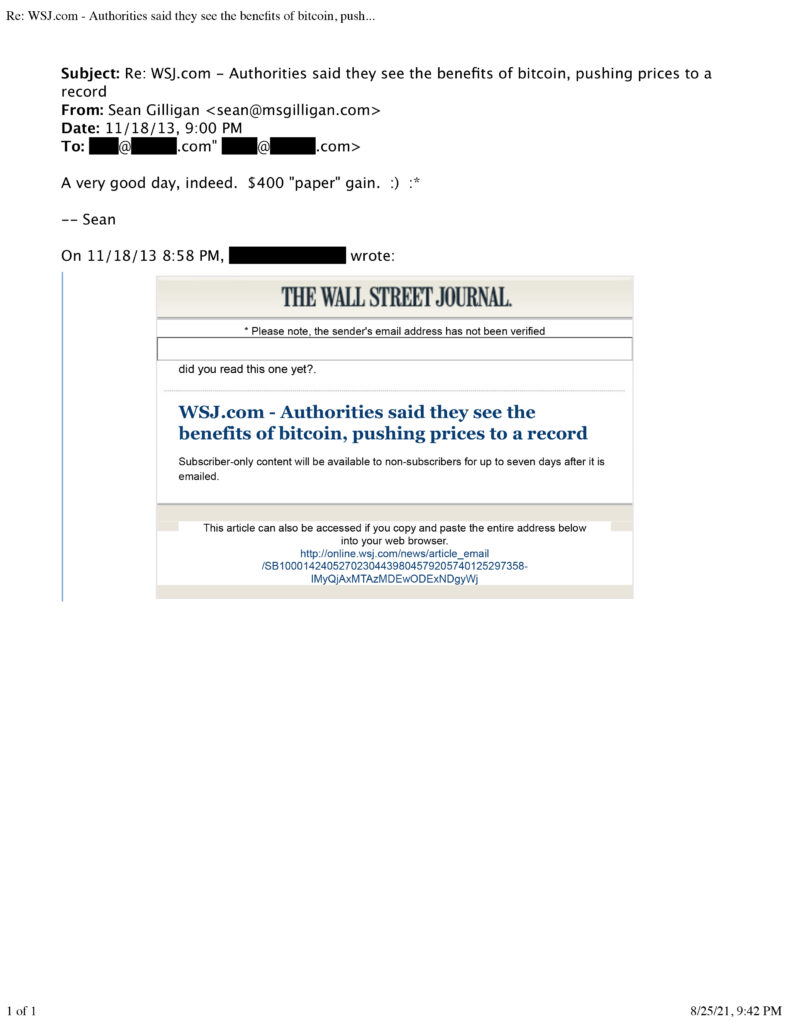

Crypto came into the story in 2013, when he started coding, investing and trading in crypto. All that he talked about for years with family, friends and colleagues was crypto.

Yet he swore repeatedly in Court documents that he only controlled under 1.2 bitcoin when the couple separated in April 2019. In six years he accomplished almost nothing!

He announced a one-day crypto gain in November 2013, and spent significant gains in 2017 on a family vacation in Ireland. But he claims that he did not invest or trade. He attended crypto conferences every year all over the world, places where his fellow enthusiasts met and traded, and yet claims that he made no money trading in crypto.

It’s as if he is claiming that he was a professional gambler who visited Vegas regularly but never gambled there!

********

His couple’s tax history helped teach Sean how to hide his crypto assets.

His initially prosperous startup failed early in their relationship, and he could not accept this failure. He refinanced twice and then took out a second mortgage on the couple’s home. An inevitable result of the ensuing bankruptcies, foreclosure and financial hardship was that tax problems arose.

According to the IRS, Sean had neglected to pay to the IRS his failed startup’s employee payroll taxes. These tax debts, which were his alone, were not discharged in the couple’s bankruptcies. Because of these debts and his libertarian belief that taxation is theft, Sean‘s tax problems worsened during the marriage. He refused to sign or file any tax returns himself for several of the 18 years of the marriage.

Probably the most distressing consequence of Sean’s refusal to address the couple’s tax questions occurred in March 2012, after his long-suffering wife had arranged a payment plan with California’s taxing authority, the FTB. Sean was supposed to sign a particular form in order to take advantage of that plan. He failed to do so. The FTB garnished the couple’s entire joint account, thousands of dollars in one fell swoop, because Sean would not sign on to a $300 per month payment plan.

The couple immediately became “unbanked,” and no longer held operating bank accounts. When Sean had a bank account, money passed through it rather than remained on deposit, so that the IRS and FTB could not garnish what was there. He wasn’t going to let that kind of garnishment ever happen again. He used cash and crypto and avoided deposit accounts.

There were costs to being “unbanked.” Some, like the cost of the money orders with which Sean paid rent and for the prepaid debit cards with which the couple paid most other bills, were relatively minor. Some, like the 2-3% that he paid check cashing services to cash his payment checks from clients who did not have a local bank account, added up (he cashed the checks of local clients at their local banks). Those clients without a local bank account included Rivetz, the one company that employed him during the marriage, which was located in Massachusetts. In 2017 and 2018 alone, Rivetz paid him close to $200K a year, at a cost to his family of something like $5,000 per year!

Tax evasion is not cheap!

Keeping the couple’s funds in his sock drawer or crypto gave Sean extraordinary control of all of the couple’s money. His ex- never knew what he did with most of his Rivetz earnings and most of the couple’s other money. He doled some of it out to her and used some more to charge up prepaid debit cards for the couple’s living expenses. He ran some through bank accounts and crypto exchange accounts, all used for spending and holding nothing material on deposit for any length of time. She no longer had the protection of a joint bank account holding family money; she no longer had checks to write herself.

From Sean’s point of view, hiding his assets in crypto beat hiding them in his sock drawer. Cash has the distinct disadvantage of never appreciating. Crypto, whether or not it is the enormous ponzi scheme that it appears to be, can and does appreciate, and over the years the gains in the more established cryptocurrencies have exceeded their losses.

Sean must have been grateful finally for the IRS and FTB, because avoiding their clutches pointed him in the right direction to avoid sharing the couple’s crypto community property with anyone.

********

Investing in crypto is a better way to hide money than a sock drawer. That’s why the IRS and other law enforcement authorities are so concerned about it: money-launderers, ransom hackers and the like love crypto’s evasive capacities. Real money converted into crypto is almost impossible to locate.

Stage 1: The branding about the blockchain holding a fixed and transparent record of every transaction forever is reassuring. In fact, locating hidden crypto is terribly hard. Crypto itself is a kind of skullduggery! When Sean made his legally required disclosures in the divorce, they raised more questions than they answered.

Sean did disclose one cryptocurrency wallet, but it was one that he himself had coded in large part during his years of consulting for Omni, the Omni layer or Omni Foundation (crypto entities change their names a lot; Omni never seems to have incorporated anywhere).

This wallet takes self-prepared to a whole other level; not only were the contents self-prepared, with hand-written notes and modifications in the initially sparse court filings, but the medium holding those contents, the wallet itself, was pretty much self-prepared too. Sean did much of the coding himself.

Tell me that Sean can’t play with that data however and whenever he feels like it!

He has admitted various crypto transactions which don’t appear in that Omni wallet, for example a $4,950 capital gain declared on his 2018 tax return (filed separately), but has yet to identify which wallet(s) that gain occurred in.

Another example: he admits to purchases and sales of small amounts of crypto at the Santa Cruz Cryptocurrency Meetup, which he cofounded in 2014 and has run ever since, maybe 150 meetups, but professes to be unable to locate any records of these transactions.

This sort of stonewalling sounds trivial because, if Sean won’t or can’t produce the records, they can surely be found elsewhere. Right?

Stage 2: Wrong! After Sean’s failed self-disclosure, he had dealt with Coinbase and other crypto exchanges, third parties like banks and brokerages, which sound like they would furnish account statements of Sean’s holdings.

Far from it.

Accounts in exchanges can potentially be hacked or, more importantly, subpoenaed, meaning compelled to disclose their customers’ holdings over time. Most exchanges compete with each other to be as unresponsive as they can to subpoenas so as to reassure their customers that disclosure of their crypto assets by subpoena is more than unlikely. They compete by being based offshore (e.g Sam Bankman-Fried’s FTX in the Bahamas), to make it harder to serve them with subpoenas or other legal papers from those having claims against them or simply seeking information.

Almost every exchange and major crypto player hides from such informational subpoenas, often (like Bitfinex and Sam Bankman-Fried) in a tax shelter jurisdiction.

More crypto-skullduggery!

An expensive crypto expert did convince Circle, another exchange, to disclose what the applicable subpoena sought. Of course, this was after Sean had denied having an account there which he could access! In response to his lies, his ex- was obliged to spend good money obtaining information that Sean was supposed to provide himself. At least Circle was located in Massachusetts and accepted service there.

BitFinex, an exchange with relationships with Tether and Omni, a long-term client of Sean’s, refused point blank to give her anything. Most BitFinex and Tether entities are located in the British Virgin Islands, and can only be served at a cost of around $1,000 each. Yet because of these entity relationships, Sean is more likely to have had an account at BitFinex than at other unrelated exchanges.

And Tether and BitFinex, whose crypto bro senior management and controlling shareholders are pretty much interchangeable, are widely accused of market manipulation and other financial fraud. When they have spent a fortune fighting federal and State regulators and paying penalties and the like, as they have done, how can Joe (or Jill) Blow expect them to be frank and honest in a divorce suit even if the excessive amount needed to serve them is paid?

Another deterrent: cryptocurrency exchange accounts rarely hold much in the way of crypto for long. This is because crypto owners are all about hiding their crypto, and allowing third parties like exchanges to control their crypto makes it discoverable. The accounts allow individuals to exchange different types of crypto with each other or for cash, and for trading with third parties whom the individual does not know. Only newcomers, whom Sean calls “crypto-newbies,” leave their crypto on deposit for any length of time with any of the crypto exchanges.

Experienced players like Sean leave all their crypto wallets in “cold storage,” meaning under their own control, and not the control of an exchange or other third party, and unconnected to the internet most of the time. “Cold storage” means on a thumb drive or comparable digital storage device.

How can anyone locate what is on a thumb drive somewhere?!

Experienced players like Sean prefer to purchase, sell or trade crypto in person, so that no exchange is ever involved. If an exchange is involved, the players are normally in and out as quickly as possible.

Stage 3: Addressing the crypto-skullduggery that Sean engaged in to undermine court-ordered disclosure of his crypto assets.

Cryptocurrency has its own evolving language that we knew nothing about when this divorce proceeding started in 2019. Sean had already been using that language since at least 2013. And crypto bros caught on to lawyer’s games in using language, where if you don’t pose the question in exactly the right way, with exactly the right terminology, the person answering can duck the response that you are obviously looking for.

An example of Sean doing this kind of crypto-skullduggery occurred in response to his ex-‘s lawyer’s April 2020 request for “public keys” to wallets that Sean controlled in order to access those wallets herself. Crypto bros tend to control multiple wallets: here’s a random Quora answer on the question: “Diversifying your wallets is as important as diversifying your portfolio in general. . . . Using multiple wallets protects your crypto in much the same way that decentralization itself protects a coin from ‘issues’ like theft.”

Sean replied to this simple question three months later by ignoring its obvious thrust. “By public keys, I believe you mean addresses. This is not a reasonable request because addresses are generated for every transaction but not all wallets allow interfaces that allow viewing or exporting addresses. The keys would not show values and, further, the key information is provided in the transaction logs which are included.” Because he creates cryptocurrency wallets in his work, that may actually mean something. If so, I still don’t know what! You can see why I call this kind of evasion crypto-skullduggery!

Here’s another kind. In October 2021, the judge forced Sean to disclose documents revealing the couple’s crypto assets under his control. In response, Sean stated repeatedly, as he had done all along, that he had disclosed all of such documents in his possession.

That statement was likely accurate. But divorce law intends that he produce in court all of the records of the joint crypto wallets under his control. Only then will he reveal the couple’s assets. His statements that he had produced all documentary records in his possession were only accurate if he had deliberately avoided printing most records of his crypto wallets. In practice crypto wallets held in cold storage have no documentary records other than those printed by the person controlling them.

Saying that “I have given you every document that I have” may be accurate, but it’s again what I call crypto-skullduggery. Especially as Sean also swore to having made a “reasonable effort” to locate such documents. Couldn’t printing them have been done with reasonable effort?!

Stage 4. Could a cryptocurrency expert help to locate Sean’s crypto wallets?

Undisclosed wallets are almost impossible to locate, because unlike bank, brokerage or some exchange accounts (other exchange accounts allow owners to identify themselves simply with an email address made up for the purpose), none are identified by the owner’s name, social security number or other personal identifier: they are strings of 26-35 random digits (I think!) sitting on the crypto blockchain with millions and millions of comparable strings.

Think finding a needle in a million haystacks!

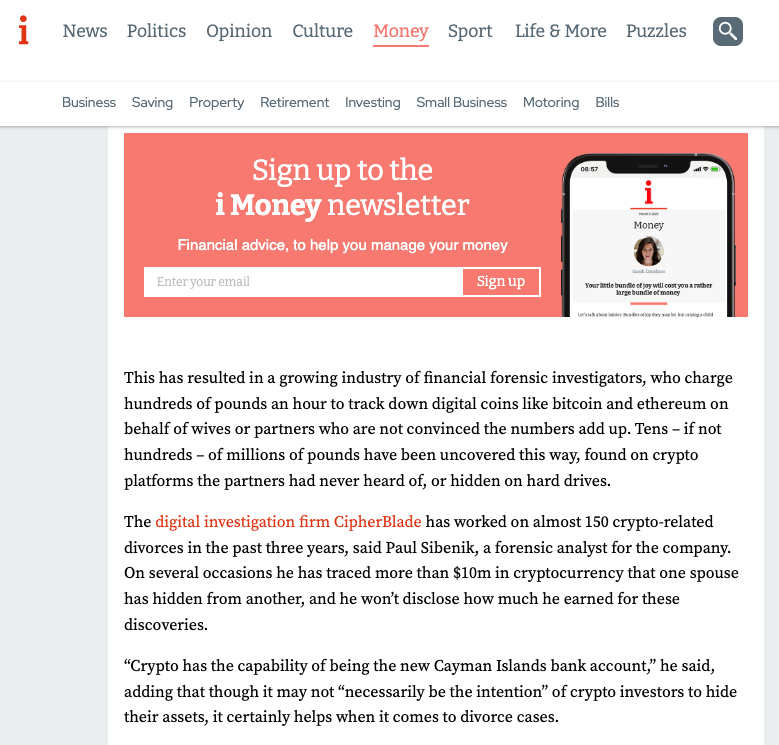

A Wall Street Journal article attacked ShapeShift, a crypto company that Sean was intimately involved with. His “best friend” during the last five years of his marriage, Sarah Blincoe, was the sister of its former CFO, Justin Blincoe. ShapeShift engaged CipherBlade, a crypto expert, to defend their reputation. Many divorcing women also engage CipherBlade, at $650 or more per hour!

15.5 hours of analysis and investigation goes very quickly, and costs over $10,000! What CipherBlade could do was speak the crypto language, which enabled them to ask the right questions and respond coherently to questions raised by subpoenaed exchanges. In other words, they were armed to address exchange crypto-skullduggery.

CipherBlade did help obtain Sean’s Poloniex account records, referred to earlier. But little else. These crazily expensive experts might have been able to help an average investor’s spouse to locate hidden cryptocurrency, because when it is moved into crypto from alternate investments it is traceable. But Sean, a coder in the field, knew that and spent a lot of money (by check-cashing, for example) to enable himslef to copnvert cassh into crypto without passing through any traceable institution.

Stage 5: What’s next? Could Sean’s former employer help?

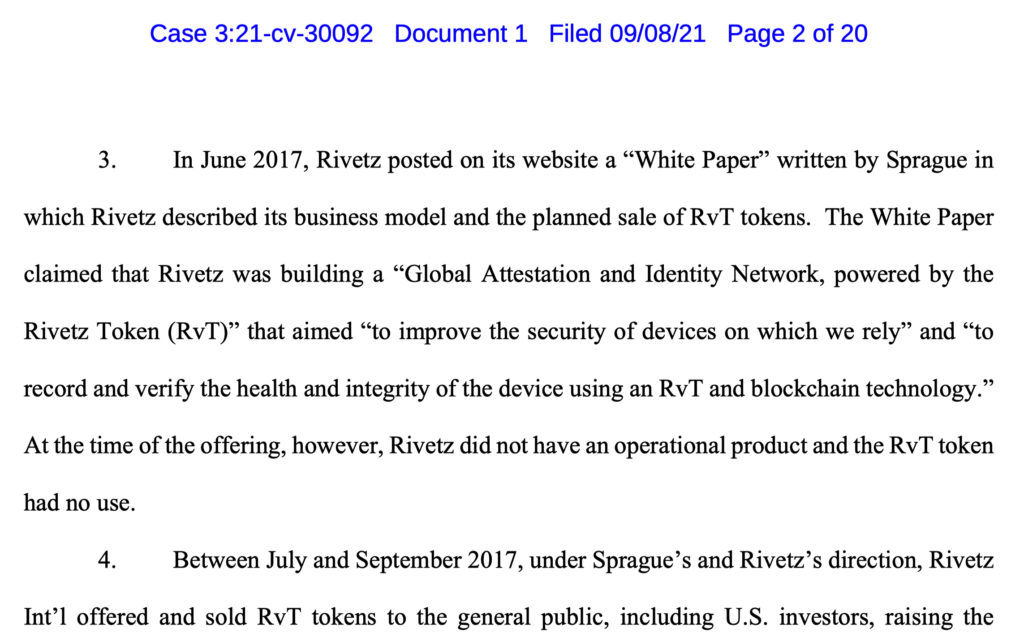

Rivetz had been Sean’s only employer during the marriage: most of the time he made what money he made by consulting or trading in cryptocurrency. In the normal course, a spouse can easily obtain her spouse’s earnings information from his employer. Not here!

In his court filings, Sean denied having received anything above his declared salary from the company. He had been promised a six-figure bonus if and when Rivetz completed an offering of its tokens.

And it did complete that offering!

Unfortunately, Sean was laid off by Rivetz at around the time of the couple’s separation, and the company pretty much closed its doors a few months after. The normal channels for seeking corporate information (VP HR, CFO or Controller) about what Rivetz had paid him, in cash or crypto, were closed.

Typically bonuses to employees in crypto offerings are paid in crypto. Investors paid in Ether for their tokens, and the easiest crypto for Rivetz to give Sean was thus Ether. Yet Sean had not disclosed any Ether wallets.

It gets more complicated! In September 2021, the SEC sued two Rivetz entities (one offshore) and Steven Sprague, Sean’s former boss, for violations of federal securities laws and defrauding investors in Rivetz! Sean had had one real job in 19 years of marriage, as VP Engineering, and the feds are prosecuting his employer!

Here is the federal prosecutor’s summary in the Complaint of what Rivetz did wrong:

“Between June and September 2017, defendants Rivetz, Rivetz Int’l, and Sprague offered and sold digital tokens called “RvT.” More than 7,200 investors worldwide purchased RvT tokens for digital assets then worth approximately $18,000,000. Over 30% of these investors were located in the United States. Defendants marketed the RvT tokens as an investment opportunity, . . .. But, defendants’ offer and sale of RvT tokens was not registered with the SEC, and investors did not receive the disclosures required by the federal securities laws.”

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION, Plaintiff v. RIVETZ CORP., RIVETZ INTERNATIONAL SEZC, and STEVEN K. SPRAGUE, Defendants.

Steven Sprague likely retains some Rivetz records, and will certainly remember whether or not he paid Sean a bonus in crypto.

But Steven is a crypto bro, like Sam Bankman-Fried. Steven used a portion of the proceeds of the RvT token offering to buy a house in Grand Cayman, just as SBF bought real estate in the Bahamas from FTX’s crypto dealings.

Steven is avoiding service so that he cannot be obliged by subpoena to disclose anything else. The Feds are likely already being pretty demanding!

Obviously, this story isn’t over. The Court is convinced that Sean owned more crypto than his one disclosed bitcoin wallet. By ordering him to pay $33,500 in two installments to his ex- to help with her discovery, the Court is doing its best to fulfill its mission of uncovering the truth.

But major challenges remain to be overcome in this hidden and devious world of crypto.

Asking third parties has definite limits: Tether and Bitfinex, discussed above, were one example. Steven Sprague is easily avoiding service in Massachusetts, and there’s very little that can be done as a practical manner by a California divorce court to oblige him. He can’t hide from the SEC, but from a poor ex-wife, he certainly can.

Crypto is itself a kind of skullduggery. Add in lawyer skullduggery, and it is really hard to uncover any hidden crypto. That’s what makes money for the crypto bros. That’s why crypto exists.