My summer vacation, taken early this year, focused on trains. I fitted in a few friends and family, of course, but this vacation was all about trains. Most of them were real, although there was a special one in Paris that was imaginary and beautiful.

The view from by bedroom window in the Cairngorm Hotel in Aviemore. The buildings opposite are the train station, and there is fresh snow on the mountains in the distance. On May 20th!

Last summer’s vacation in Scotland had included a disappointment: the Caledonian MacBrayne ferry to Mallaig from the Isle of Skye had broken down, and as a result I had missed seeing and riding on the Harry Potter steam train. So this summer I was going to start with that train.

Of course, the best laid plans of mice and men . . . While still in California, I tried to make a reservation online for the Harry Potter train, known as the Jacobite outside of the movies, a tourist train owned and operated by West Coast Railways. There was no space available at any time during the week I was planning to stay in Scotland. Eek!

The Strathspey Railway, showing the locomotive which pulled my afternoon tea train. The company supplied this photo of the train leaving Boat of Garten station. Neither train nor weather was quite as appealing for my ride!

I modified the plans slightly, still taking the first Caledonian Sleeper train to the Scottish Highlands after arriving at Heathrow, but this time making Aviemore my first stop. Aviemore had its own steam train, the Strathspey Railway, and online in California there was no difficulty reserving space on this one.

I even had an afternoon tea on the Strathspey train, of scones, clotted cream and strawberry jam, a bit tackily served, but a nice touch nonetheless. Aviemore was lovely, even in classic “variable” Scottish weather, everything from heavy rain at one point (snow settled on the Cairngorm mountains above the town) through periods of bright sunshine interspersed with high winds, all in a day and a half.

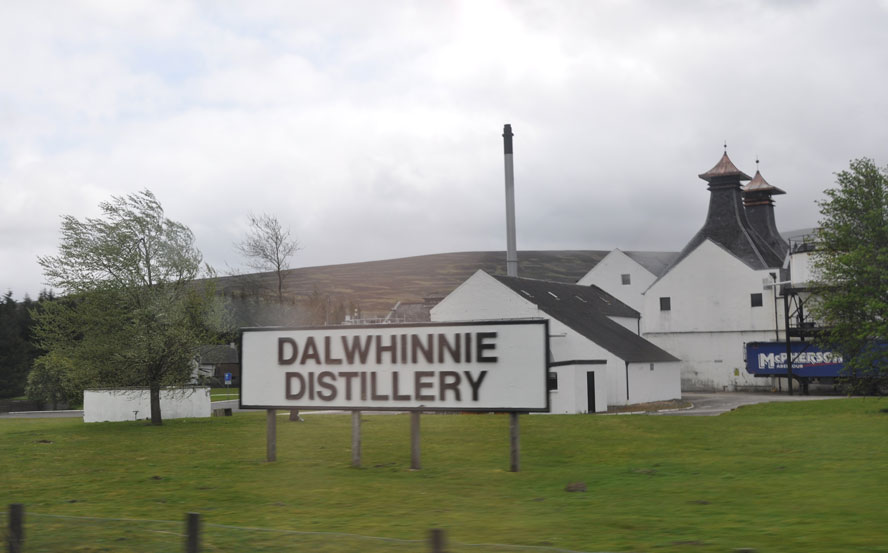

The Dalwhinnie distillery, seen from the train. The guide said that it was the highest distillery in the Highlands, at over 1,000 feet. The trees are bending in the gusting wind.

The high point was an early morning bike ride on a bike rented the afternoon before. I knew that I would wake early because of jet lag, and sure enough was in the saddle by about 4 am. Nobody moved on the moors around town, candlelit by the northern dawn, and I rode on in a peaceful and still silence before disturbing two deer at the side of the road. One, the smaller, ambled away, almost indifferent, not at all scared. The other bounded off in fright, zig-zagging across the heather and barking each time he hit the ground: a beautiful sight, and a bizarre sound.

I also took a tour of the Dalwhinnie distillery during the afternoon. It was only a fifteen minute walk from the station, just a few stations down the line from Aviemore, but that was a cold and blustery walk. The wind blew and gusted in my face, going both directions it seemed, to and from the distillery. The occasional showers had me bowing my head and squinting while the wind whipped the rain into anything approaching a hole in my clothing. All told, a very Scottish walk on a very Scottish day.

First sight of the “Jacobite,” Harry Potter’s train to Hogwarts, at Fort William Station. Until the films, there was never a steam locomotive of the red color of the Hogwarts Express. This black locomotive is more typical. The carriages in real life are the same color as in the film.

After a break for soccer at Old Trafford down in England, I finally arrived on another Caledonian Sleeper in Fort William, home of the Harry Potter train. There had still been no reservations available on line, but I had noticed on the reservations web page a little note to the effect that the train’s guard would have a few tickets available first come-first served on the day. I crossed the platform from the arriving sleeper to find the guard on the Harry Potter train, which was waiting for its scheduled departure for Mallaig. There were several people without tickets, and she accommodated us all. We were on!

Another steam train at almost exactly the same spot, this one photographed in 1987 when Sunshine, Nick and I passed through town during an October vacation in our little Ford Transit van conversion.

What a fabulous ride! For no particular reason, I have other photographs of steamers at this station and on this line at other times dating back to 1966-7. But, probably because of finances, I had never been able to take the steam train on it, until now. It was worth the wait.

Just as it had in Aviemore for the first steamer of the holiday, it was raining, only showers at first. Some of the passengers were a little disappointed that the droplets of rain trickling down and across their windows blocked their view of the stunning vistas we passed by. It wasn’t a complete blockage, but the scenery was harder to admire. Bad weather interferes with so much on vacation!

The Jacobite at steam on a curve, taken by leaning my head out of the open carriage window. That steam locomotive whoomp-whoomp is just a great feeling.

In this case, it didn’t bother me. I simply opened a window at the end of the carriage and peered out. We had been advised not to do this, because of the vegetation growing so close to the line, but I did it anyway, just as I had done fifty years before as a trainspotter. I learned as a child to check for possible obstacles while leaning my head out of the window (the sign above every one of those 1960s windows read “Do Not Lean Out of the Window!”), and the skill had not gone away. I watched the engine whoomp-whoomping away up the track, and the carriages snaking along behind. I saw the rain showers lash the mountainsides, and the wind whip the waves on to the shore approaching Mallaig.

The Hogwarts Express’s most famous landmark, the Glenfinnan Viaduct, itself on a curve. I have no idea how this viaduct, on a branch line in the distant Scottish Highlands between two fishing villages, could ever have been worth its initial cost. With a total of 21 arches, the tallest about 100 feet high, it was completed around the turn of the last century (1901).

Mallaig, a fishing village and ferry port, was in the middle of a storm when we arrived, about two hours after leaving Fort William. I walked out toward the rocky ocean front, and was almost blown backwards by the force of the wind coming onto the shore. The blustery day that had begun in Fort William had taken a turn for the worse. I retreated into the village, found a lovely pub with a combination of a working coal fireplace and a working wireless connection, and checked emails while lunching on fish and chips. A conference call with IBM was scheduled for after we returned to Fort William, and I wanted to prepare.

I found other trains during the vacation. At York, after another look at the wonderful National Railway Museum (free admission!), I did a little trainspotting for old time’s sake. Trainspotting is not complicated. You stand on a platform and take down the numbers of locomotives or multiple units which pass by. As I walked along the platform, this Freightliner goods rolled through in front of the station cafe on the footbridge.

The call never happened, at least not for me, because of our extraordinary ride back to Fort William into the face of a major storm. The weather had broken by the time we reached Mallaig, and by the time for the trip back the storm was at its height.

Our first hiccup, soon after leaving Mallaig, was a branch that had apparently fallen, not across the line, but leaning into the path of the train. The footplate crew stopped and apparently examined it, because we waited for five or ten minutes before slowly chugging on. The only way that I knew what had happened was that the branch whipped along the side of the carriage and against its windows as we passed it by, making quite a thwack.

Here’s a more typical trainspotter’s view of the station. We normally stood at the end of the longest platform, so that a train at any platform did not block our line of sight to another passing through or on its way out. From this end of the platform, you can see a glimpse or more of three trains. The one in the foreground is one of Sir Richard (“obsessed with virgins”) Bransom’s Cross Country trains.

Our fun was not yet over. The wind was gale force now, the rain was constant, and we were going up a steep hill. We whoomp-whoomped to what felt like a delicate halt.

I wondered if there was another fallen branch. There was a pause, and then we tried to advance: we barely moved, a few yards at most, and then the locomotive briefly whoomp-whoomped rapidly, and we came to a halt. The train stood still again, a little longer pause this time. I was admiring the scenery and trying to figure out what was going on. It seemed clear that for some reason we could not advance. At the end of this longer pause, we backed up, maybe a couple of hundred yards. “That’s the wrong way, guys!” I thought to myself. We paused again, and then took a run at the hill. This time we stopped even earlier.

Yet another steam locomotive, this one a GWR pannier tank at Bodmin. It is owned and operated by the Bodmin and Wenford Railway, which has offered steam service in Cornwall for 25 years. What was I doing in Bodmin? Guess!

By now the guard was telling us what we were beginning to guess, that we were having trouble climbing this hill, the steepest on the line, and that the locomotive’s driving wheels were slipping on the wet rails. The strong wind too was playing its part, because the curve in the cutting at the top of the hill allowed the wind to suddenly blow at full force straight at the front of the locomotive. She (the guard) reassured us that she was sure that we would get up and over the summit with the next try, because the steam railway’s most experienced engine driver was now taking over from our current driver. We held our collective breath.

This is the most extraordinary stretch of the Great Western Railway’s main line from London Paddington to Penzance. Brunel built it along the seafront through Dawlish, the town on the hillside behind the train. I loved this spot as a child and then as a trainspotter. We took holidays nearby a couple of times. During this visit, I hauled the suitcase along the sea wall to Dawlish Warren, putting paid to the suitcase, which lost a wheel somewhere along the way.

We backed up further this time, maybe half a mile or so, and then stepped on the gas, figuratively speaking. Although we must have accelerated up to around 30 mph pretty soon after starting this run, we slowed and slowed as we climbed, and by the time of the curve at the top of the hill, we again ground to a halt after the locomotive briefly whoomp-whoomped rapidly. That was apparently the sound of the steam turning the driving wheels with no traction. A half a mile run up did not carry us over the summit. I was beginning to ask myself whether there enough hotel rooms in Mallaig to house this entire train load of passengers if we couldn’t finally make it back to Fort William, and the answer was pretty clearly no. There were maybe 50 hotel rooms or other tourist accommodations in the village, and we were numbered in the hundreds.

This is Paddington Station late in the evening. My grandfather and his brother worked here for most of their respective careers with the Great Western Railway, but I was just here to catch a train. That is the one on the platform to the right, the Penzance sleeper train.

At this point we were about an hour and a half behind schedule, the pauses between remedial actions were getting longer, and the guard was looking a little worried herself as she bustled along the carriages addressing diverse passenger concerns. Everyone realized that we weren’t supposed to be going backwards and forwards like this!

We backed up again, this time by a good mile, maybe more. Another pause. Then off we went again. There was less immediate acceleration this time, and we seemed to be going pretty slowly as we neared the top of the hill, but this time, finally, we kept going past the farmhouse which had marked the limit of our progress thus far, around the bend and through the cutting at the top of the hill. There was no rapid whoomp-whoomping this time, and the passengers cheered. Somehow, even though it all felt pretty much the same as the previous attempts and even though we were cresting the summit and had not yet started our descent on the other side, we all knew that we had made it.

The passenger notification that greeted us on our return to Fort William. No trains running anywhere in Scotland! Fortunately, Fort William does have quite a few hotels, and I found a nice room within the hour. The power then went out in the hotel, restaurant and all, and I had the feeling that we were back in Santa Cruz, where power goes out almost every storm. That’s called a smart grid: not!

At least, we made it back to Fort William, after more fun and games. This was wild country without a storm. With one, there were obstacles everywhere. Back in Fort William we were greeted with the news that all train service in Scotland had been cancelled because of the storm, one of the most powerful of the year! Trees were down here and there all over, apparently, and the powers that be had decided that discretion was the better part of valor. My plans changed again: instead of moving on to Oban as planned, another beautiful trip across the Western Highlands with another distillery to tour at its end, I just about found a hotel room in Fort William. Almost all had been snapped up when the train station essentially closed its doors. Bit of a real Scottish Highland day, all things considered!