I just loved to see those enormous and pounding steam locomotives. Still do, to be honest. I can feel to this day the early unspoken glee I felt as a boy when those great grinding and hissing machines rumbled, roared and whump-whump-whumped by. They passed by Aunty Alice and Uncle Bert’s house near London when we visited them, giving me a good reason to look forward to visits there. They powered along the South Devon coast, sometimes right along the sea front, whenever we took one of our regular vacations to Paignton. They were even a plus in Paignton, where everything was fun. Whenever I saw one, I felt good.

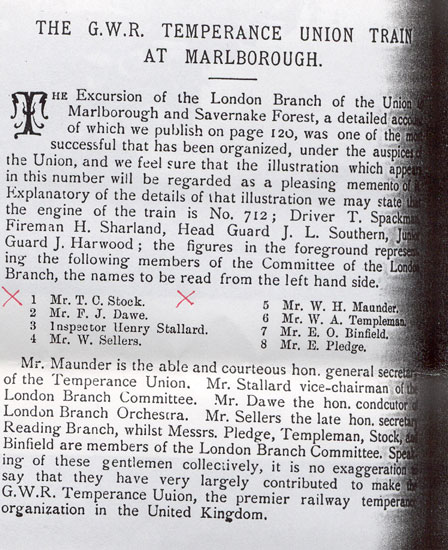

An early Great Western Railway Stock, Thomas Charles, member of the London Branch Committee of the G.W.R. Temperance Union. This article is dated 1895.

Where did that youthful passion, my first passion outside our close-knit nuclear family, come from? The answer is imponderable, a conjunction like many real passions between my introduction to them and some deep inexplicable predilection. If we only knew the source of particular human passions. Do they reflect any kind of reasoned choice? Are they almost completely haphazard? Could they be genetically implanted, like eye color? The backdrop to this particular passion that I would learn much later in life, long after it had waned, was that dad’s father, uncle, grandfather, great grandfather and great great uncle had worked for the Great Western Railway for well over two hundred and twenty years between them. That is a lot of genetic material. I didn’t know it when I learned to love steam locomotives.

Mr. T.C. Stock with his Temperance Union colleagues. According to his gravestone, Thomas was born in around 1855, which makes him about forty years old in this photo. He and his wife Elizabeth lived to 1932 and 1935, respectively. Temperance apparently gives you a good innings. He was my great-great grandfather.

The Great Western was one of the original British railroads that rode the wave of the industrial revolution from Paddington Station in London to Birmingham, Bristol, the Southwest and South Wales. My grandfather with his weak heart and his brother Uncle Bert with his simple son were clerks in the GWR’s offices at London Paddington throughout the 1930s, except in granddad’s case for when he was in hospital. By some mischievous fluke my own father was not only born near Paddington, but somehow contrived to die there even though he had never worked there, no longer lived there and only ever passed through on his way elsewhere. My great great-grandfather, Thomas Charles Stock, was a foreman for the Great Western in Paddington at the turn of the twentieth century.

My favorite railroad ancestor was my great-grandfather, who was the Goods Agent at Reading General until his retirement in 1939. I never met him, he died a couple of years before I was born, after his son my granddad, but the fate of the railroad depended on the efforts of its Goods Agents, who were only a level or two below the Railway’s Board of Directors. The engineers went down in history, those like Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who built the railway and its bridges from London to Bristol and Cornwall, or Sir William Stanier, who worked on the Great Western at Swindon Works with another of my more distant ancestors, Walter Stock, before being poached away by the London North Eastern and designing some of the most respected steam locomotives ever built in England. But the engineers’ work would have come to nothing without the Goods Agents making a commercial success of the enterprise.

Great-granddad Frank Stock, at home in Caversham, near Reading, in 1943. He had retired from the GWR in 1939.

Those Neanderthals of the industrial revolution, steam engines, are pictured in a poster on the landing at home in Santa Cruz. I found it in Paris in about 1993, could not resist the impulse to buy it, and contentedly walk past it every time I go up or down the stairs. It is a “Hall” class steam locomotive, the long-haul workhorse of the Great Western, in the industrial gloom of Paddington station in 1937. It is such a sad photograph, as a well-crafted black and white can be, capturing with its momentary exposure the pathos of an era. The locomotive idles awaiting the call to labor again, quiet as unseen workers prepare its next journey, always another journey.

The poster is a reminder of the sweet regret of a passion long gone. Steam locomotives were already doomed when I first discovered them: I was simply too young then to know their future or care about it. The steam locomotive’s origins in the dirt and grime of the industrial revolution foretold its extinction despite the excitement that it brought into the lives of small boys. Hundreds of horsepower that looked and sounded like hundreds of horsepower, nothing that I have ever seen, not even a 500 megawatt electric power generating plant, could ever match their sheer pounding guts. They duly became extinct as I spotted, the inevitable commercial result of their high cost in labor and engineering inefficiency relative to diesel and electric locomotives. I pursued trains and continued spotting them, only realizing much later that the hobby had become less satisfying because the objects of my affection were no longer its target. Spotting diesel or electric locomotives was like seeing a lover after the thrill had gone. You go through the motions, you even feel some of the same things, but in time you have little inclination to continue. The diesels and electric locomotives were more powerful, cleaner and more efficient, but they were esthetically almost sterile and hopelessly uninspiring.

Mum and dad subscribed for me for years to this magazine about trains. I retain very few issues, having cut photographs out of many to make scrapbooks of trains when they were my passion and later thrown out many more. This is one of the few remaining covers.

The first steamer-oriented activities that I remember are Dad taking me to Stapleton Road station in Bristol from time to time on a Sunday afternoon to watch the trains go by, and Michael Palmer and I riding our bikes in boyhood excursions to the main line to the Severn Tunnel. Stapleton Road was twin platforms, almost bare in my memory, with no stopping trains on Sundays but a few odd goods trains or express passenger trains passing through, but never too fast: the station was on a bend in the track. Dad and I would sit a little, or walk backwards and forwards, not a lot of conversation, and leave after a couple of trains had passed. Communion with a small “c”.

Michael and I shared something more. We would climb over the wooden picket fence with its flakes of paint and missing pickets and up the embankment to be close to the express trains as they pounded by. What a thundering, childhood thrill! There was the smell, a mixture of steam and grease, that seemed to emanate from the ballast itself. Then there was the sight of those monsters! A steam locomotive looks impressively statuesque when an adult is looking at it close up in a museum. Imagine how it looked with the white steam pouring out of its funnel, or spitting to the side out of the driving cylinders or gears, roaring by right in front of a young boy’s face! The ground itself shook as the locomotive hurled by at 50 or 60 miles per hour, whump-whump-whumping on its awesome way, and we cowered in the weeds beside the track and looked on in fear, flinching as it pounded out the rhythm of its enormous driving wheels.

As a teenager, even in my twenties, I told people that Michael and I played last across in front of those pounding monsters. “Last across” is a game of chicken. You run across the railway lines just in front of the arriving train, and the winner is the last one across. Children died from playing it during my childhood years, perhaps a little foot tripping over a rail or more likely on some loose ballast. Only a few died, making the newspapers each time. I might have made it up for Michael and me. We were very close to those trains, at the top of the embankment, but I doubt that we were stupid enough at that young age (mum and dad left Bristol soon after my eighth birthday) to risk life and limb for bragging rights. Or maybe we “ran” across a couple of times with plenty of time before the train arrived. That is the one that I tend to believe now, a pantomime of risk shared by two scared boys caught up in boyhood bravado. At some point I should look up Michael again and see if he remembers.

In Birmingham, the love for steam locomotives liberated me from many of the domestic constraints of my peers. I adopted train spotting as a hobby. This seemingly banal hobby allowed me to travel further and further away from home for longer and longer periods. Much of the time, I was alone, after dad served as a guide a couple of times to check that it was safe. As a family, we were getting tighter and tighter, closer together with each passing year, with each move, but one of mum and dad’s great strengths as parents was always their ability to let me go when I wanted to. It confuses me a little, in that it runs counter to mum’s efforts to monitor me constantly to avoid accidents. But she probably needed some respite from the level of duty that she imposed upon herself, and by the time I was leaving for the whole day I was perhaps ten years old and generally able to look after myself.

I no longer have the Ian Allan book listing the steam locomotives numbers’ that was my bible as a train spotter. Someone must have thrown it out. Maybe me. This is the closest thing to it, a listing of the classes of locomotive running on British Railways in 1962. I never liked the cover, a new diesel locomotive.

At first, I would pass on football some evenings and cycle after school to the closest railway line and wait for the trains to come. There were not many trains on that branch line, those that came tended to be the slower diesels, and I would often suffer from a small boy’s extreme impatience and frustration. But each time one passed by I would duly note its number in a small exercise book converted for the purpose from school use. Then back at home I would look up its number in the train spotter’s record book published by Ian Allan that I had convinced mum and dad to buy, which had all the numbers of all the locomotive power on British Railways, and underline the ones that I had seen. If I had already seen a particular locomotive, I would not underline it again. The object was to spot and underline as many as possible.

There was not a lot of spotting to be accomplished on the little branch line not far from home, which led easily to the next step: on Saturdays, from about the age of ten, I would take the train on the little local branch line into Snow Hill, the main line station in the centre of Birmingham, and train spot my heart out for most of the day. It wasn’t a bad deal from mum and dad’s point of view. Children paid half fare for train tickets, and there were cheap day-return tickets available outside commuting hours. My lunch cost practically nothing, because I would barely eat meals, preferring to limit my culinary pleasures to different chocolate concoctions. Snow Hill was a relatively structured environment, with men in uniform all over the place if I had any real trouble. The trains ran in all directions, and especially on summer Saturdays, when the cities of England, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Leeds and the like, emptied to the holiday resorts on the South coast, the train spotting was rich and exciting. Which is not to say dynamic. During an eight-hour summer Saturday at Snow Hill, I would see perhaps 25 or 30 trains, several of them local diesel multiple units that I had seen before and thus uninteresting for two reasons: they were diesels, and I’d already spotted them. The day was hours of waiting, dawdling along the platforms, looking in the café and at the chocolate in the candy kiosk, not talking with anyone, interspersed with the occasional thrill as a steamer whump-whump-whumped its way into the station.

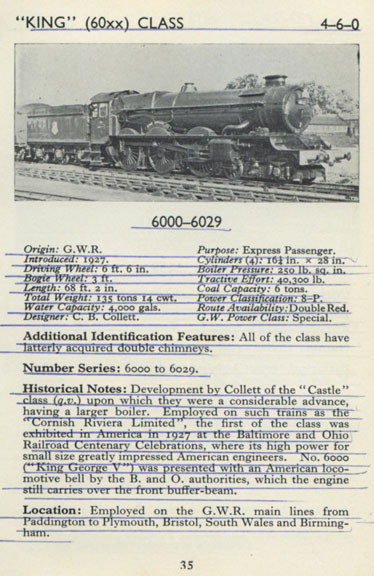

Here is the page of the Observer’s Book of Railway Locomotives devoted to the GWR’s “King” class. It recites that their power for their size was extraordinary. I underlined the text because I had spotted several Kings.

Our obsession, those of us spending the day on Snow Hill’s platforms spotting, was Kings, not the royal family, whose value and interest has always escaped me, but the Great Western’s flagship and most powerful steam locomotives. They were rarely programmed to run through Snow Hill any more, even on summer Saturdays, and so spotting one was a rare treat. From the front they had broader cylinders like the Castles, which differentiated them from the Halls and Manors, the other classes of the main line steam fleet that passed through Snow Hill. As one pounded into the station, and steam locomotives hauling heavy trains always pounded into every station that they entered, we would crane our necks and call out: ‘it’s a King!” “Nah, just a Castle.” “Must be a King, it’s been weeks since we’ve had one ‘ere!” And so on, and sometimes it was a King, but mostly it wasn’t, but I for one was never dissatisfied. The diesels that were soon to replace them were already being seen in Snow Hill from time to time, and would be the exclusive motive power by the time I left Birmingham in 1966.

The grave of Thomas Charles and Elizabeth (née Watts) Stock and Ann Stock, my great-great-grandparents and great-great-great-great grandmother. I found the grave in 1994 after reading in the Stock family tree (then residing with Martin Stock down in Cornwall) that they were buried in Paddington cemetery. The cemetery is no longer called that, and many of the older graves had been “cleaned up” (read destroyed), but we walked right up to this one without a guide.

I say “we,” but no-one was with me on the platform at Snow Hill. We were a temporary community of convenience brought together by a shared love for trains in general and steam locomotives in particular. I was one of the youngest, which generally served as my protection from the male against male problems that tend to surface in male groups, and these groups were exclusively male. Women like my mother were not fond of trains. Perhaps they pounded too much. Mostly she complained about the dirt and said that they cost too much for the three of us, and we took buses in preference to trains to go into Birmingham shopping with mum when dad was at work.

Oddly enough, the dirt that we saw from the top deck of those double-decker red buses gave me my memories of what has always felt like the bad side of Birmingham. What was a part of the drama in Snow Hill was depressing on the outside. Looking back at one point, I think during my early 40s, the drab greyness of the scenery that we watched during those bus rides became the epitomy of the depressed England of my childhood. The land of the falling drizzle, I called it later, in contrast to the Empire where the sun never sets, the colonial advertisement that was still heard in the Conservative press. They had yet to realize that we had given up the Empire, one of the after-effects of the Second World War. In later years when I returned to the UK, I was always shocked by sunny days. They seemed to be abnormal interruptions of the greyness of my childhood.

Birmingham brought the first death during my life in our family’s little world. Uncle Alec, Aunty Vi ‘s husband, died in 1961 at age 58 on the operating table. Mum and dad were really upset. Here are Vi and Alec with their older son Dave at Bekenscot, the model village near Slough, where they lived then. This was taken in around 1950.

It was not just that we were economically depressed in those years, although that was surely a part of it. The whole country was still suffering from a terrible and terribly expensive war. The war had seen the government steal the metal bars from the fences surrounding the churches in central Birmingham to forge into artillery: mum had explained that to us. Think about that one for two seconds: the opposite of turning swords into ploughshares! I didn’t notice the irony at the time, of course. I noticed the feet of the fence posts remained, sticking incongruously and alone out of the dirt or the grass. They were never replaced. As the City Center was renewed, different barriers appeared, but the metal posts never returned around the churches. The war had seen the government mortgage the entire country’s future borrowing to fight the all-consuming cancer that was Nazi Germany. The peace was a relief only from the war. It was scarcity, dirt on every building that was not new, and drizzle that never seemed to stop. Until 1964, we were all immersed in a seemingly interminable hangover of greyness and drizzle and industrial grime.

Dirt is inside people as much as outside. I got off relatively easily when real meanness caught up with me one day at Tyseley locomotive shed, which was just off the railway line between Shirley where we lived and the center of Birmingham. I went to the shed because it was a golden opportunity to spot dozens of steam locomotives at rest. I went alone because it was easier to sneak into the shed, which was railway property and did not allow visitors, as a child alone. Plus, none of the other children I knew shared my passion for trains. Two bigger boys who were also train spotting in the shed started talking to me and told me that a King had come off the tracks on some waste ground behind the shed. I saw a picture in my head of the brave monster upended on the waste land, reflected in a pool of water, but sort of knew that this was not possible, and remember even arguing with them that I would have heard about it or seen it if such a crash had in fact happened, but still agreed to let them show me. Mum and dad had warned me about strange men in cars, and if these boys had been men or in cars I would not have gone with them. As it was, as soon as we were away from the shed they started hitting me and threatening me with much worse. I was terrified and shaking and taking punches around the head.

One of the two was much meaner than the other: it was already engraved on his face. After threatening and taunting me for a while, how long I could not say, he started kicking me and forcing me down toward one of the standing water ponds that dotted this wasteland. It must have been an abandoned gravel pit. I couldn’t swim yet, and was terrified that they would force me into the water, just to get me wet. What if the water was too deep for me? Should I tell them that I could not swim? No, bad idea, that might give them the roadmap, lead them where I most feared that they go. How not to look terrified when I was shaking like a jelly?

This is what it was all about, a steamer at speed, here a “Castle” class locomotive named after one of the GWR’s engineers. It was taking on water from a trough in the track racing along the fast stretch between Reading and Paddington. “History of the Great Western Railway, Volume 3,” by O.S. Nock, published by Ian Allan.

My luck held, and his friend intervened and gently called the meaner boy off, letting him punch me a couple more times before laughing at me as I ran away almost hysterical with fear. It was probably that very fear that protected me, rather than my good luck. It satisfied his desire for power. I shook like a jelly for all of ten minutes. It was not the pain: being punched, even kicked, by another kid was surmountable. It was the inexplicable meanness, not yet tempered by the realization that the kinder kid’s lack of meanness had saved me much worse. What if he had been as mean as his friend? What if they had egged each other on to bigger and better things? What was the point of it? Why? Not just why me, but why so mean? Where did the hunger for that kind of power, to inflict that kind of humiliation, come from? Even looking back now, it is hard to see a justification for what happened on the wasteland behind that shed. The boys were white like me, dressed like me, growing up in post-war England just like me, train spotters just like me. If I only knew.

The real bullying of my childhood, the Cypriot boy when I was looking for boys to play football with and these two train spotters at Tyseley, were not extreme incidents, especially when compared with the insane stories of incomprehensible meanness that I have come to know since, the Nazis in their concentration camps, for example, or the cunning horror of serial killers. But mine had been a modest life in terms of experience of meanness, and these little incidents were very powerful in my small boy psyche, benchmarks against which the darker side of life would be understood and measured forever. For whatever reason, or more likely for no reason at all, some people are simply mean, or are more mean than not, or more expressively mean than not. A child cannot see his or her own meanness, and we all have some. So when meanness is first thrown into stark relief in others it is a shock, even if the extent of the real harm suffered is small. Mum and dad were horrified, of course, and called the police and British Railways about what was happening at their shed, to no avail. Anonymous meanness is notoriously hard to find, or to attribute responsibility for. I knew that it was not the railway’s fault.

It was the flip-side of my most valuable childhood asset, independence. Train spotting brought me the better side of life and days that are still framed in lights forty years later. One of them occurred in April 1964. For most of my life I remembered that day as being a birthday present, but in the light of mum’s diaries it was perhaps a treat for having done well scholastically. It was two months after I sat for a scholarship to attend Solihull School, long enough for us to find out that I had won. Maybe it was a reward. That would have fit prevailing patterns. Doing well at school brought me great rewards.

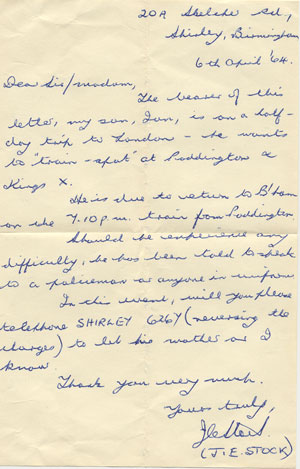

Dad’s letter asking that he and mum be informed if I experienced “any difficulty” on my day-trip to London from Birmingham aged 11. Dad’s uneasiness about letting me go alone for the whole day is visible in his inaccurate statement that it was a “half-day” trip. It was a long day!

Mum and dad bought me a day-return ticket to London Paddington, the Great Western Railway’s London terminus, about a hundred miles away. They gave me enough ready cash for lunch, chocolate and other snacks, as well as to take a tour by tube of some of the other main line termini in London, the stations where the routes from all over the country, not to speak of Scotland, Wales and France, terminated and disgorged their throngs. It was all so thrilling. Not just all the trains that I spotted, both at the stations in London and those that we went through and at locomotive sheds that we passed by on the way there, in Banbury and at Old Oak Common. But also the 100-mile journeys each way all by myself, and the challenge of finding my way around London, one of the world’s great cities, alone for the entire day. Off I went, with bated breath, heart pounding and, less prosaically, an envelope in my pocket that I was to give to someone in uniform if I was in trouble. I still have it. The note inside reads: “The bearer of this letter, my son Ian, is on a half-day trip to London. . . Should he experience any difficulty, he has been told to speak to a policeman or anyone in uniform.” Dad added that he would pay the long distance charges if a telephone call home was needed.

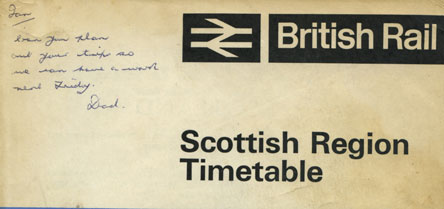

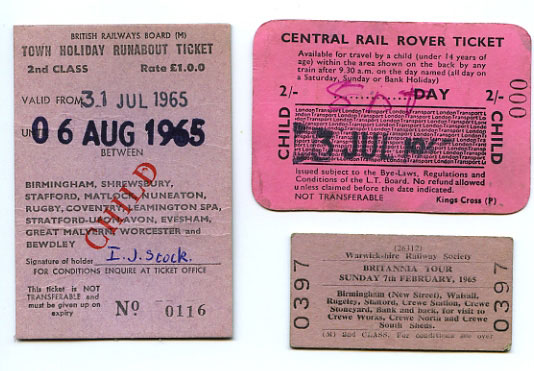

This is the front cover of a British Rail timetable from 1966. Periodically mum and dad helped me wander here and there on the railways, so that I could train spot almost around the clock and in places that I could not normally reach. I spent a week in 1965 travelling all over the Midlands on a “Rail Rover” ticket, the predecessor to Britrail passes. I fitted a lot of miles into that week! I also made trips on the train during our Scottish summer holiday in 1966. Dad bought me the above to help plan those trips.

There were those who thought that mum and dad should not have let me go alone. As a parent now, I see their point. But I felt so special and so spoilt, because it was such a great present for a train spotter, not because I had the good fortune to be given such freedom. I did not realize at the time that freedom was what I was being given. I asked dad a few years before he died why they let me do that sort of thing alone, why to my mind he and mum initiated that sort of thing. “If we didn’t do it, you’d have done it by yourself anyway. We wanted you to do it with us, not against us.” That was a revelation when he said it, although in light of the emotional tribute that mum was demanding with such regularity, I must have desperately needed room to breathe. Dad was very, very quick, and would not have missed either the desperate need or its cause.

The day trip to London was close to ultimate train spotting for an eleven year-old. I had learned how to get the number of the trains going the other way at speed from a moving train, or at least most of them, by fixing the number plate (on the side of the cab) with my head through an open window as we approached it and twisting and withdrawing my head somehow as it went by. I could get the four or five numbers on the side of the cab with that flick of my head. Then there were other locomotives that we passed, and dozens at and outside Paddington when we arrived. Its London terminus was the heart of this railway, with local trains coming and going to Slough and Reading every hour or more often in rush hour, express train locomotives, both steam and diesel, moving off to the depot for service or bringing their next train into the station, and other locomotives idling with no clearly defined purpose outside the station on a siding or at an unused platform. I scribbled away as busily as my little hands would allow.

This Science & Society 1957 aerial view of Euston gives some sense of the serial additions made over time. The rails fan out into the wide swath of platforms.

These train spotting trips were also memorable for the interesting people I was learning how to meet, and the conversational skills I was developing. For an eleven year-old, I was extrovert, interested in almost everyone I met, especially away from home, and often complimented by relative strangers as engaging, a nice boy or something similar. From somewhere, perhaps trying to keep track of mum’s moods and feelings, perhaps as a way to ease into one of the regular new schools and new friendships, I had developed a penetrating intuition and a real interest in what made other people tick. On that trip down to London, I befriended a young woman, perhaps in her early twenties, and remember guiding the conversation regularly during the hour or more during the trip that we were talking where she was interested in going. How I knew it, I could not say. I would stick my head out of the window as we passed other trains or through the more important stations, Leamington Spa, Banbury, and the like, but then when we would talk again. She kept talking about herself, delighted to do so, and I made a real friend whom I would never see again.

Finding my way around London that day was not as hard as it sounds, because anyone will help an eleven year-old boy asking for help, even women alone, and because I had been warned of strange men, I normally asked women in public. In any event, clear, color-coded maps of the tube network adorned every tube and train station, and the signposts helping show you how to find the right platform for your destination were impressively easy to follow. I made it to several of London’s principal train stations, ignoring only those that I knew had almost no steam locomotives left because their lines had already been electrified. It probably took me about ten trips on the tube that day, maybe a couple more.

A sample of my 1965 train spotting trips: a week in the summer touring around the Midlands, a day in the summer on the tube touring around the main line termini in London, and a club visit to Crewe works. Dad came with me to Crewe: I traveled alone for the rest.

Euston and Kings Cross, neighbors on the Marylebone Road, were the highlights of the trip. I had never visited either before. Euston, gateway to Northwest England, North Wales, Ireland and Western Scotland, was the first London terminus, built in 1837 and extended in different directions several times. It was already dusk by the time I walked into it, and in the half light this grand Victorian monument was like nothing I had ever seen. Main line termini were typically built under an enormous glass and metal canopy, high enough to let the smoke from the locomotives escape, and big enough to let the light of the sky in. They were roomy and gracious spaces, despite the ever-present grime and dirt. Euston had two or three of these canopies, but the space between them and around them was a striking maze of dirty yellow-painted corridors, open spaces and rooms of all sorts for passengers or staff. 130 years of extensions had created a labyrinth whose sense was imperceptible to the casual visitor.

For a bastion of the industrial revolution, it was oddly quiet. The hiss of the idling locomotives did not really penetrate this maze, and I padded along in the oddly alert state that an unexpected environment can induce. What lights there were appeared more gas than electric, and lit only a halo of space around themselves. The Victorian mist, echoes of Sherlock Holmes on Baker Street, less than half a mile away, hung over the dank and oily platforms. Loaded or empty hand trolleys for hauling supplies and boxes appeared out of the mist strewn across my path, abandoned empty or loaded, dimly lit and hazy. Aging porters in scruffy uniforms trundled by on mysterious errands, and carriages, freight cars or even entire trains appeared out of the shadows. I padded on, between clusters of commercial flotsam, to find the spot where I could see the most locomotives coming and going, at the end of the longest platform. There I stood for a while, not long: I would soon need to return to Paddington to catch the train home. I scribbled down engine numbers under the last lamp on the longest platform. The steam locomotives were uniformly black in the half light, their escaping steam or pounding smoke lit in flashes as the halos of the lights were passed by. I was in a smoky, dark and soon to be extinct heaven. Euston was completely demolished a few years later as the railways finally, belatedly, renewed themselves, and I never saw it in its original form again.

Kings Cross, just down the street, has to this day never been completely rebuilt, and still hosts the Edinburgh, Newcastle, Leeds and York trains to the capital. By the time of my first visit, this day of boyish freedom, the beautiful streamlined Gresley Pacifics of Aunty Rose’s place, the fastest steam locomotives in the world, were already playing second fiddle to the undoubtedly more powerful Deltic diesels that were destined to replace them. This was a pattern that was repeating itself across British Railways.

This map adorned most compartments of Western Region carriages (in 1948, the GWR had become the Western Region of British Railways) when I travelled on them to train spot. Interestingly, our family life was led pretty much exclusively in the area encompassed by this map: Slough and Marlow are just west of London, Slough on, and Marlow to the north of, the main GWR line; Bristol and Cardiff are toward the West across the Severn Estuary from each other; Birmingham is to the North West; and even Paignton is in the Southwest, below Torquay. I gave this to dad as a birthday present at some time in the early ’70s. He liked it, and hung it above the bar at home. It is © 1959 by British Railways.

At Paddington station on my way back home, before I knew that dad had been born near there or would die there, or that his father and uncle had worked their whole lives there, a barley sugar sweet got stuck in my throat. It was scary for a small boy and it hurt and I couldn’t seem to swallow. Mum and dad had told me to find someone in uniform if I had a problem. I carefully followed the signs to the Station Master’s Office on platform 1, and dutifully asked someone in uniform, the Station Master himself as it turned out, for help. He was very nice to me, gave me a glass of water to ensure that the sweet had in fact been dislodged, and explained that my throat still hurt because the sweet had bruised the back of it and not because it was still there. He took a little believing, because it really felt as if it was still there. But thanks to him I got over it before panic set in.

He had one of his staff put me on the train home, making me feel special and pampered. With the darkness making it impossible to see most of the number plates on the few locomotives that we passed on our way back to Birmingham, I spent most of the trip peering outside at the passing scenery, trying to penetrate my own reflection in the compartment window. The only time that there was anything to see was when there were lights of one kind or another, and I watched patiently for lights for most of the two-hour ride home. Somehow, they seemed solitary when we passed them by. There is an exquisite small sadness in any solitary light in mist, and I watched light after light in the quiet countryside and even quieter towns that we flew by. Uniformly alone, uniformly swathed in mist, their halos preoccupied me and, for the first time that I remember, gave me the feelings in the world around me. Here was I, a very small fish who had been in the biggest pond in the world, London, for a day. I didn’t think or feel that, of course, I was eleven years old. But the solitary lamps above the muted streets in the quiet towns, and the lonely lamps outside of a farmhouse or a cottage on a country lane, those I felt somehow, and keenly. I spent the whole trip home to the arms of my parents immersed in the sadness of those solitary lights and in memories of the day’s tableaux, the Gresley Pacifics at Kings Cross alongside their more powerful but still poorer diesel cousins, the maze of Euston in the mist, the oldest big city railway terminus in the world, the Paddington station master and his sage advice on barley sugars. I was in awe. I was such a lucky boy.

© Ian J. Stock

Next chapter: Chapter 10 The Tough go Shopping

Previous chapter: Chapter 8 Football