Here are my two younger offspring mocking their aging father mercilessly as he makes a sterling effort to improve his physical condition. Maman offered me the stepper for Christmas 2003, and I duly jumped on it regularly, for a thousand steps until the counter broke (made in China), and then for 25 minutes until it broke again, and again. It died completely by 2006. My stepping on the stepper fascinated Charlie and Alex, who exercise constantly and all day long without the benefit of anything more substantial than a soccer ball or goalie gloves! Just to make sure that I got the point, Charlie one day jumped on the stepper and effortlessly, without breaking a sweat, stepped more steps with less weight than I had in less time. Thank you, lad! I do get the point!

I love being a dad. No doubt about it, it’s a wonderful thing to be a father. Especially in this family!

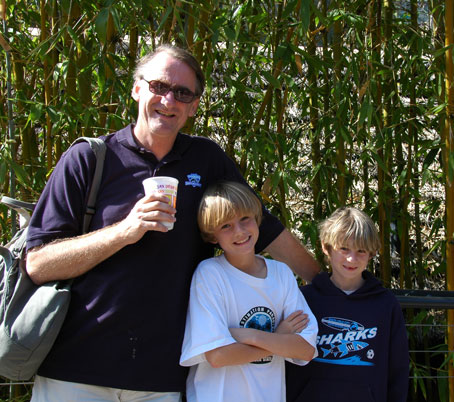

This was taken at home in Santa Cruz at Daphné’s family birthday celebration (of course, there was also the friends’ party, on video, and the school celebration!) at home in August 2000. THIRTEEN!!

But you would be forgiven for suggesting that I would be a better father if I had done a better job of my relationship with the mothers of my children! Can’t argue with that. But whatever the symptoms of my broken marriages, and there have been quite a few symptoms, I will always be grateful to Sunshine and Marie-Hélène for giving me such wonderful children.

The problem with the divorces from their mothers is precisely the effects that the divorce has on the children. Children don’t like divorce, period. Their dislike is manifest in many diverse ways, some of which appear dotted around this journal. When the divorce turns into excessive conflict, as did Sunshine’s and mine for years and years, the children absolutely hate it.

Such excessive conflict has even characterized Marie-Hélène’s and my divorce at times, which I must confess I don’t understand. We were in mediation for a while, and that process, combined with my paying her a lot of money to help her adjust back to independent life, kept things calm at first.

But then she quit the mediation, and became increasingly bitter and angry. This is not the place to go into the reasons for the divorce, but this anger made little sense to me because, in my mind at least, those reasons were not of my creation. Well, except of course to the extent that my personality flaws made their not inconsiderable contributions to the break up! Classic divorce confusion.

Another at Disneyland in Anaheim, this one with Charlie and Alex in February 2006. The older children, then aged 19, 18, 16 and 16, were no longer interested in weekends away with the parents. Sigh! I adjusted slowly to that.

As a result, we ended up in a protracted judicial process, and the children have become troubled at times over the years that this process has dragged on, even the older ones, who are more detached because of their ages and increased independence from their parents. The children could handle their troubled feelings so long as Marie-Hélène and I kept the conflicts down. For whatever reason, we failed to do so sufficiently.

* * *

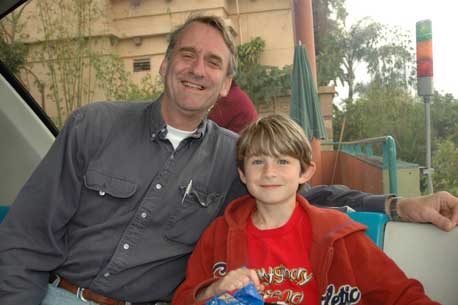

Back at Disneyland in Anaheim in 2006, on the monorail. The flip of this photo, with maman and Charlie across from us in the compartment, is on the Maman page.

Divorce was the part about being a dad that never occurred to me in advance.

I suppose that the young men of my generation were dimly aware that parenting was a likely next step, like marriage. If I thought about becoming a father at all, which was rarely until my early 20s, it was in this vague and distant manner. I did think that dad was a good father, and vaguely wanted to be like him. No divorce there.

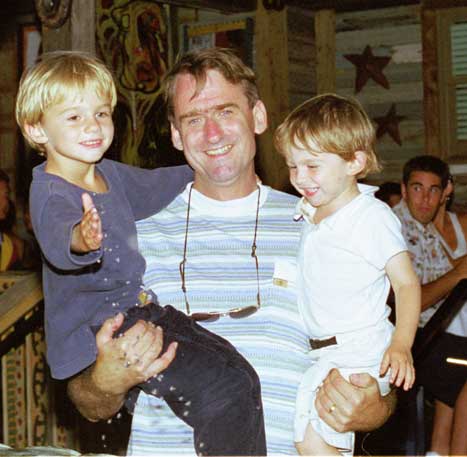

Here we are in August 2000 at The House of the Blues in Downtown Disney, just outside Disney World, Florida. Charlie is splashing the fountain on the restaurant’s terrace. It was a great meal! All the children were there. The red nose is a reminder of the Irish and English ancestry: we weren’t built for the sun!

Then, Antony and Laura arrived and made concrete the idea of becoming a dad, an idea which, thanks to them, began to appeal to me.

Sue, my sister, and Derek had married young and brought Antony into the world in 1975. I spent as much time as I could (hard work, considering that I was in Berkeley and that they still lived in England) with this little chap and his baby sister Laura, who arrived in 1977. I saw them during every English vacation, and they even visited California and traveled around here with us a couple of times.

A calmer shot from a sunny beach in Southern Brittany, during a two-day trip from La Grée in 2004. The beach was near a village called Telgruc. One of your children lying next to you, and all is well with the world.

I remember getting up at 5 am to look after them in Yosemite Valley when we all visited there together in around 1981, so that Sue and Derek could sleep in for a few days. Antony had just turned six, and Laura was about four. I had the normal twenty-something approach to early mornings: to be avoided at all costs! But these mornings were special, sleepy and quiet, with the children chit-chatting delicately in their pushchairs as I pushed them along the trails around Camp Curry.

How long after precious moments like these with Antony and Laura did it take to have children of my own? All that I remember is that those years felt very long: I was ready!

Nick and Tom, born in 1986 and 1989, were my first sons. Sunshine was their mother, and Nick was born before we left New York and Tom in Paris. Like us, most new parents have a fairly similar reaction: yikes!

This photo is one of that rare breed taken with all of the children. Of course, they’re not all smiling: that would be too much to ask, particularly of teenagers! The occasion was Charlie’s 12th birthday, in August 2007. Alban was getting ready to cut a little more cake, as he was indicating with his left hand!

For one thing, Nick had colic. If you haven’t been exposed to colic, you win that one! In retrospect, the illness probably did not last more than a few months. But as it ran its course, he hurt when he was hungry, and cried and cried until he ate. Then he was mostly quiet while eating. Then he hurt while he was digesting, and cried and cried again until he finished digesting. At which point, he began to get hungry again . . .! And most of the time, for “cry,” read “scream!”

That’s a key lesson for parents. You often can’t control or reason with the apparently selfish and insistent needs of your baby. I couldn’t use logic or anything else to convince Nick not to scream. I had to live with it, and subordinate my own impatience and frustration to it. I barely noticed what was happening. There wasn’t time. Just taking care of even a well baby’s needs is a full-time job that you have not been trained for.

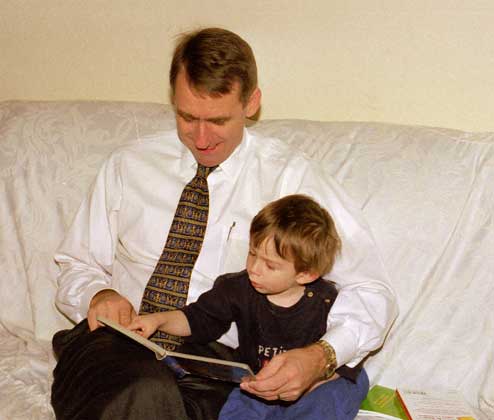

Alex reading to his dad, in January 2000. He wasn’t yet two years old. Dressed for the office, this must have been taken before leaving for WSGR or after returning.

Time was my big problem from day one. Having been up all night when Nick was born, I then checked right in at the office after a 50-block walk downtown, before returning home on the subway to sleep. This was not masochism. My chosen profession is very demanding. Corporate law takes pride in making excessive demands of its practitioners. Phrased like that, corporate law sounds a lot like a baby before it develops the capacity to reason! That is an accurate impression, let me tell you.

With Tom, Alex and Charlie, at Carentoir, near La Grée, July 2001. I think that this was the last time that either Nick or Tom stayed at La Grée. They miss it.

Trying to satisfy the competing demands of children and legal employers has been a way of life throughout my fathering years.

In the early years, corporate law won. I couldn’t afford to antagonize New York law firm partners of a generation who literally did not understand how anything could come before work. If they couldn’t, neither could I.

What I could and did do was leave New York, a demanding environment for associates in law firms, to move to Paris. Paris was very good for children on an institutional level, and I hoped that it would also be good in terms of the time that my job demanded.

But the Paris firm too was American-owned and managed, and its profits too were a direct function of how hard its lawyers worked. Plus Sunshine continued in her demanding legal career, meaning that both of us had professional constraints interfering with parenting.

When Charlie arrived, Marie-Hélène was no longer working (she hadn’t worked since moving in with me), and so he had plenty of maternal attention. I was less busy, but my presence was less working independently

It’s hard to say what ultimately freed me from the excessive demands of corporate legal practice, but as time went on I got better at finding that freedom. It happened first in Paris, the plus side of a lay-off, and again in Santa Cruz, ditto! I had more time for the children, through working a more normal 40 hours a week. There are still moments when I’m buried, of course, but that was no longer the norm.

During the period beginning in 1999 after the children were all together with us and before they began moving out, being a father was at its peak: it was so good that at times I couldn’t believe it. Not that it was painless: isn’t it a French saying that first they tread on your toes, and then they tread on your heart? They do. It was far from painless. Each one of them knew and knows how to drive you crazy. And from time to time she or he did. And from time to time he or she will.

Nick, Tom (visiting from Paris), Daphne and Gino (her then beau) congregated on the deck at the condo to share a smoke, It was Xmas 2010, and it rained.

This period with all of us together lasted maybe six years, and we had interludes where they were all together with us again until Tom moved back to Paris in December 2007, another two years. I can’t imagine another period of my life to come being so full of laughter and love, of misery and concern. I can’t imagine waking up again to days so rich and long and full of the unexpected.

But it’s okay if nothing comparable happens in the future. I’ve had my time surrounded by the vibrant energy and unmanageable motion of a tribe of beautiful bright children, my own beautiful bright children, and I’ll always have the memories of those extraordinary and fabulous years. And you are sharing them here.

I spent almost a year, June 2003 through April 2004, living and working in Orange County (in Southern California), 400 miles from the family, and commuting home to Santa Cruz on weekends. On a family level, it was not a good move, even though the family visited this home away from home a couple of times. It was in an apartment complex in Irvine called Villa Siena, where this was taken in the swimming pool late in 2003. It’s a bit blurred, but you can see that it was fun. We sure love pools!