By some strange coincidence, two centenaries occurred this year in schools where I was educated: in New Haven, Connecticut, Yale Law School celebrated its 200th year, and in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, Sir Willam Borlase’s Grammar School celebrated its 400th.

400 years!

That made Borlase’s the winner, that and the law school’s losing its way recently. So Lisa and I attended one of the Borlase’s birthday celebrations, an open day in May culminating in a black tie dinner. I can’t remember the last time that I wore a tuxedo!

Founded by Sir William in 1624 in memory of his son – a path followed in 1885 by Leland Stanford, the railroad baron, in founding Stanford University in Palo Alto – this long visit gave me a chance to see how the school has evolved in the 50+ years since I graduated, as they say in the USA, with a ticket to Imperial College, London, in 1970.

My first day at the school in January 1967 gave me a taste of life at Borlase’s and in Marlow. Walking along the road home from the bus stop in my crisp new uniform, I was accosted by a group of lads from Great Marlow School, the other local secondary school in town. We called them “yobs” – backward boys, get it? They pushed and shoved, hemmed me in and slapped me around a bit, until I escaped and ran the short distance home. Nothing too mean, but a dispiriting introduction to the two classes in the town and the school of each. From then on, I always biked to and from Borlase’s.

Welcome!

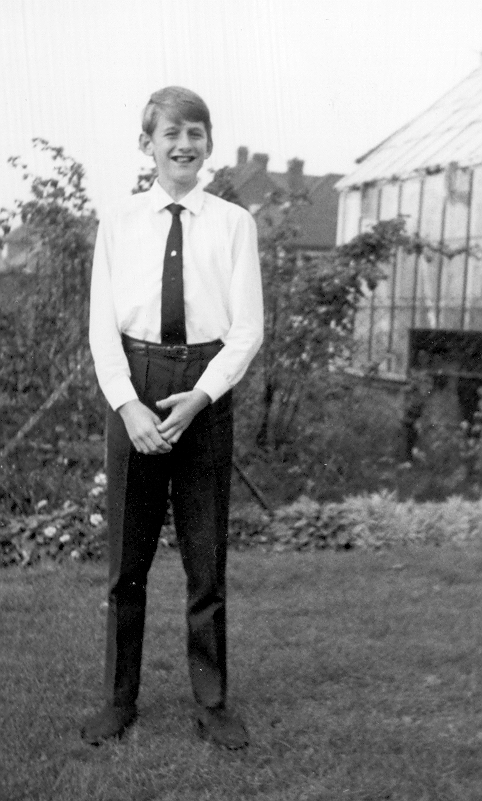

It was reassuring to be back home after a year boarding at Solihull School, but I had just turned 14 and was entering that confusing and bizarre period of life called puberty. And still in an all boys school! Puberty without girls around is more confusing than with them around; the differences between the genders that will influence the rest of your life are pretty much invisible. Fortunately, I had Sue, my kid sister, at home, but a sister is nothing like girls in the social world.

By the time I left Borlase’s, I had spent six years without girls in school and barely ever caught up those lost life lessons.

I had arrived there feeling that I was a late developer, which with my very skinny body made me terribly self-conscious and embarrassed. I abandoned school sports – after making the school rugby team at Solihull – mostly because engaging in them would have required more time visibly undressed in the communal changing rooms. Unofficial soccer at lunch and during breaks was much easier, because we all went straight back into class, only cleaning up back at home. I even talked my parents into making a doctor’s appointment with a specialist with a view to taking hormones to speed things up. Fortunately, he shot that one down, kindly but firmly.

Modern day adolescents going through that puberty hot spot would be much better served by such refusals than by the puberty blockers and transitioning surgeries that they regretfully obtain. Puberty is a terribly difficult time, and that’s it. It has no remedy except growing older.

Few others seemed to share my particular problem back then, and I’d be very interested to know what they were all going through. We knew nothing at the time about each other’s internal workings. All that we shared was (1) sports, as in football, rugby and cricket, (2) pop music, as it turned into folk and rock and blues, (3) booze, and its later cousin hash, and of course (4) bravado.

I invited four different classmates, all friends, to attend this celebration, hoping to put together a reunion table and see what insight a little age and introspection had produced. None were the slightest bit interested! As far as I could see, no-one who left around 1970 attended; the closest we met left school in 1973. Other periods in the school’s history sported many attendees at this dinner – 1990s graduates, for example – whom I deduce were less alienated during their time at the school.

In our time, despite the impressive name and charming roadside presence, the school was pretty much a decrepit little warren. (Too harsh? Perhaps. Certainly a subjective schoolboy recollection).

Buildings either needed a facelift or were “temporary,” and desks and chairs were scratched and old, deserving of little respect. We boys regularly helped them on their way to ruin: that’s the way we were. The canteen, a post-war building clearly put up on the cheap, was particularly grotty.

While academically solid, the education offered was little more than exam preparation in a limited range of subjects, and of course sports.

I saw more of the results of this alienation at a reunion of the school’s boarders back in 2010. Never having boarded at the school, I was very interested in this reunion because I had boarded at Solihull School, the source of much of my alienation from English education. How had these boarders turned out? Boarders tend to be the most alienated pupils, especially in a school which mixes day boys and boarders. Day boys at least have the comfort and reassurance of going home at night.

Many former boarders showed up to this reunion, including those close to me in age, and one of them brought his wife, the comely Jan Burton. She was kind enough to participate in the performance art that the old boys came up with for the occasion. Without going into too much detail, her performance, shared with many attending, was the Old Borlasians of my era thumbing their collective noses at the school. The spectacle was a more realistic and foolish equivalent of Lindsay Andersons’s over the top film “If.”

Now, the school has greatly expanded facilities, including several new buildings such as a home for the 6th Form (ages 16 – 18) and a purpose-built theater, and is a bustling hive of creative, sporting and academic activity. All very encouraging. One example from the school’s website: “Our symphony orchestra, strings orchestras, jazz ensembles and nine choirs perform in prestigious venues and we are recognised for our exceptional Dance, Drama and Musical Theatre performances.” Wait a minute; nine choirs, but no rock’n’roll?!

Lisa and I watched a choreographed pupils’ performance of the school’s 400-year history in the theater, a collection of skits and dances strung together with a vibrant commentary. It was a joy, and summarized entertainingly in 20 minutes the school’s complex four-century history, a history that the during- and after-dinner speeches almost completely failed to capture. Congratulations to all involved!

Then there were the interesting people we dined with. Those at our table had all started their own businesses before “entrepreneur” became such a trendy word, imported from Silicon Valley.

The four heads of Marlow’s own Rebellion Brewery gave us a glimpse of how they founded and built a business serving the local area and personifying “Small is Beautiful.” They have been brewing for over 30 years, evolving commercially as challenges like the pandemic occurred, supplied a special brew celebrating the school’s 400th for the dinner – very nice too – and now sell 40% of their beer in reusable glass bottles.

Way to go guys!

An anecdote: during cocktails before dinner in the school’s quadrangle, a parent of two pupils, whose name I forget (typical!), talked about how he became involved with Borlase’s governance after retiring from the RAF, as an Air Vice Marshal no less. He had worked extensively with the aircraft which were for many years the RAF’s pride and joy, Harrier jump jets. Jeremy Milward, who left the school about the same time as I did, was in charge of the Royal Navy’s Harrier jump jet squadron before he retired. This parent knew him and had worked with him in the ‘90s, but did not know that Jeremy is an Old Borlasian! Hopefully, they’ll be in touch again.

The dinner itself was disappointing, because there were way too many speeches – everyone and their mother wanted to have their say – and the occasional but consistent self congratulation and virtue signaling were rather dull. No dinner should include over an hour of speeches, let alone over two!

The girls, finally admitted in the 1980s, were a principal reason for the improvement felt in the school’s atmosphere. They were everywhere at that anniversary dinner, more of them than the boys (of course!), volunteering with this, helping with that, lots of ready smiles. Yes, school in my day would have been so much better if they had been there then! We thought that their presence would have helped with dating, of course likely, but it’s the feminine karma that we really missed. And of course we didn’t know that we missed it.

The girls’ effect is visible in the evolution of the school song. It used to be an informal ditty encapsulating the essence of our collective view of the school back then. “Balls to Ernest Hazelton” was a modest, short and vulgar rugby song showing schoolboy contempt for the Monk, then our headmaster. I liked the man, but the feeling was far from universal. The boarders in particular – he was their head of house, living at Sentry Hill, just as they did – loathed him. We seemed to find reasons or excuses to sing it easily, and “BTEH,” the song’s initials, was our favorite graffiti of the era.

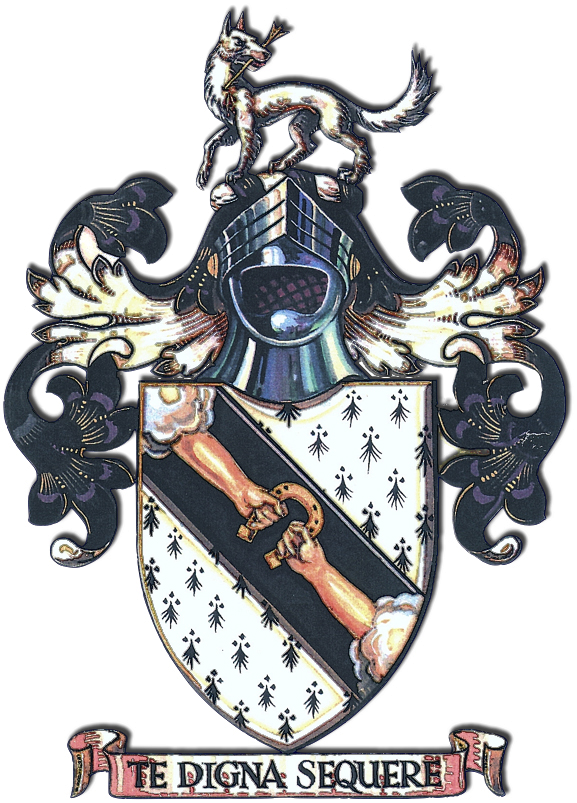

Now, the school song is entitled “Te Digna Sequere,” the school’s ancient motto. I took four years of latin, and never bothered to translate it. Teachers and administrators have adopted the song, discovered in some lost corner of the school, enthusiastically: perhaps the pupils too.

The chorus begins, and this gives the flavor of the whole song:

“Follow things worthy, follow things true,

Follow all things that are worthy of you.”

Good guidance, perhaps, but a bit too self-consciously moral for my taste. And I’ll guarantee that the boys of my day would never have adopted the new song, never even sung it once without laughing, and that the presence of girls made the switch from old to new much easier. Few girls would be caught dead singing “Balls to Ernest Hazelton!”

Money from various sources, like the girls, has visibly improved the pupils’ and teachers’ lot over the years. Political pressure to convert grammar schools to comprehensive, coupled with the poverty of post-war Britain, starkly limited our school resources in the 1960s.

At 125 pounds sterling a head, this anniversary dinner was clearly designed to make money for the school in the American way. Several major contributions, like the Rebellion Brewery’s gift of thousands of bottles of their Borlase 400 IPA, will have helped.

And the school is now one of only 163 publicly-funded grammar schools remaining in England. Out of about 3,000 publicly-funded secondary schools! And the central government funds Borlase’s, not the local authority which funds most secondary schools.

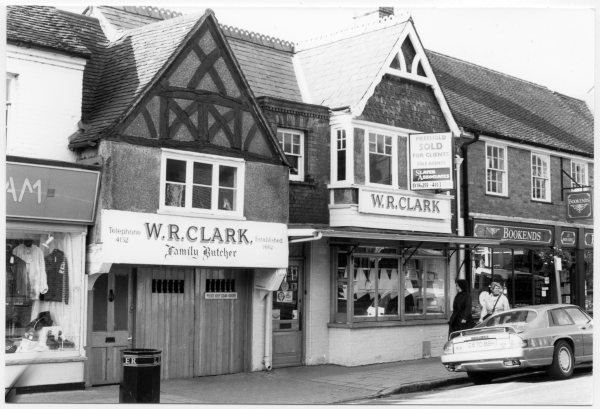

Marlow has grown significantly more prosperous over the years. A sleepy suburb of London lounging on the Thames, it has benefited from substantially wealthier residents and more prosperous local businesses. Now, for example, Russell Brand lives nearby and Ricky Gervais has a weekend place in town.

These various sources of funds have enabled more recent pupils to hit the jackpot. Their field hockey and rowing (crew) programs are nationally known, and wooden shields hanging around the quadrangle celebrate former pupils, boys and girls, who played for England, as in the national team. The level of accomplishment of recent pupils is very high in many different ways.

A couple of months after the dinner, we were glued to the TV watching the Paris Olympics in preparation for our own eagerly awaited three days of athletics at the Stade de France. The Team GB swimmers won the gold medal in the 4 x 200 meters freestyle relay! The name of one of the swimmers, Tom Dean, rang a bell, and a couple of days later I realized that I had seen that name during that Borlase’s Open Day. “Deano,” as he is affectionately known there, graduated from Borlase’s in 2018 to attend Bath University.

How wonderful that so many pupils have had so many chances to shine in so many different ways!

One reserve: only about one in 30 current pupils at the school qualify for free school meals, meaning that the UK government has determined that only one in thirty is poor. Those being educated in English secondary schools which are not grammar schools, over 2,800 of them, remain more likely to be poor and less likely to be offered as many diverse chances to shine. That sadly has not changed in the last 50 years.

Remember my first contact with Great Marlow School, the other secondary school in Marlow, walking home from the bus stop my first day? Even then the boys there sensed that we at Borlase’s had all the advantages. Wonder how they feel nowadays.